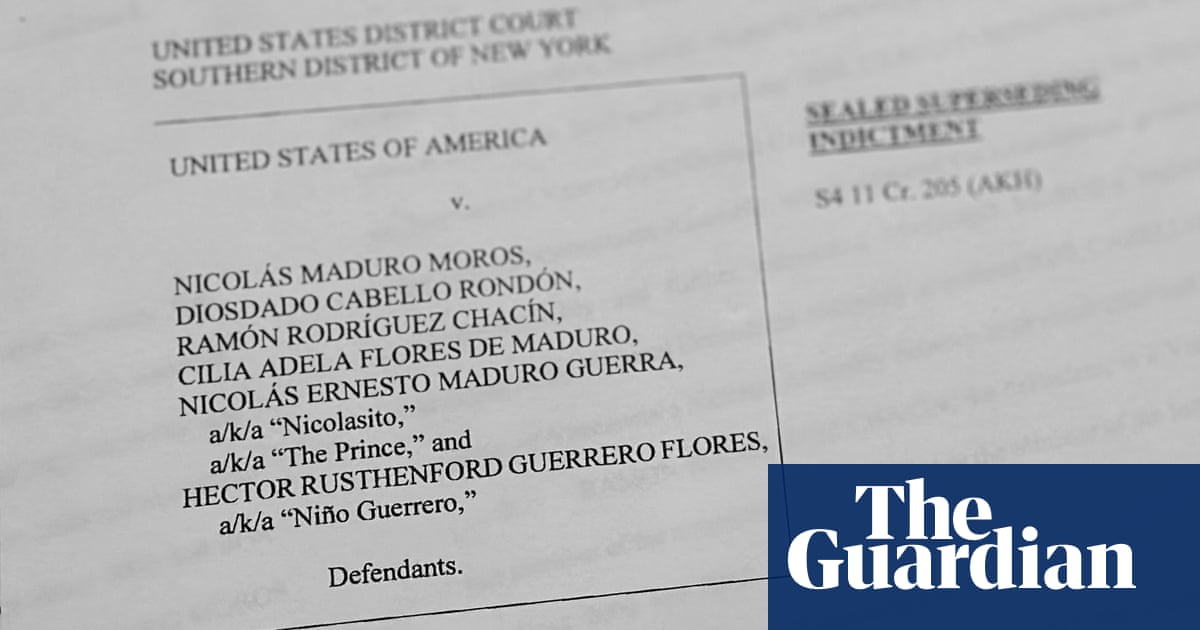

The superseding federal indictment unsealed against Venezuela’s leader Nicolás Maduro on Saturday immediately after his capture closely resembles 2020 charges against him but has several important new twists: the new indictment appears to embrace controversial claims made by the Trump administration about a Venezuelan street gang, Tren de Aragua (TdA).

Maduro was captured by US forces early on Saturday and ferreted out of the country after a series of explosions in the Venezuelan capital. The operation has drawn widespread international criticism and outrage from Democrats on Capitol Hill.

One of Maduro’s five co-defendants is the alleged founder of the gang, Héctor Rusthenford Guerrero Flores, who was indicted separately two weeks ago.

Though the indictment doesn’t allege Maduro ever met Guerrero Flores, it builds the case in court for what critics say are Donald Trump’s exaggerated and unsubstantiated allegations about TdA. Trump has repeatedly insisted Venezuela’s government sent the gang to the US intentionally as a form of guerrilla warfare, to commit crimes and spread chaos, and has used the claims to further his foreign policy and his mass deportation tactics.

The Trump interest in TdA dates back in 2024, when members of the gang were accused of taking control of an apartment building in Aurora, Colorado. At the time law, enforcement told reporters they saw TdA as a vicious group but not as a major international threat.

Still, when Trump, on his first day in office, signed an executive order to designate drug cartels and other groups as “foreign terrorist organizations”, he specifically included TdA.

The gang became a central part of the administration’s rationale to try to launch deportations without hearings, by invoking a 200-year-old law called the Alien Enemies Act, which addressed expelling people during wars, or invasions, or a “predatory incursion”. “I find and declare,” wrote Trump in March, “that TdA is perpetrating, attempting, and threatening an invasion or predatory incursion against the territory of the United States.”

The street gang was an invading force sent by Maduro, his executive order concluded, so under the law TdA members “are subject to immediate apprehension, detention, and removal”, without any court action necessary at all. The deportation of purported TdA members, with no court oversight, to El Salvador’s Cecot prison has been one of the most contested parts of Trump’s deportation efforts.

Those deportations have since been blocked by courts.

Intelligence from inside the US ran counter to all of Trump’s claims about Tren de Aragua. A national intelligence memorandum dated in April said “the Maduro regime probably does not have a policy of coordinating with TDA and is not directing TDA movement to and operations in the United States”.

The new indictment doesn’t spell out precisely what Maduro’s connection would be to TdA. Instead, it says Maduro and others “partnered with narco-terrorists”, including TdA.

A local police detective who has investigated TdA said the gang was probably the most brutal he’d come across but said based on gang members he had interrogated, they had not been directed by the Venezuelan government or even their own leadership to come to the US.

One former Drug Enforcement Administration official who had investigated the Venezuelan regime said he was unaware of any personal connection between Maduro and TdA, but said there was solid evidence of Maduro’s profiting from the cocaine trade.

“TdA has been part of the Trump narrative since the beginning of the campaign,” Adam Isacson of the Washington Office on Latin America said. “Really it’s more of a political change in this indictment. It updates or sharpens the narrative they need for the pretext for the capture.”