On a quiet headland in Donegal or Connemara today you might see a strange sight. A small group gather around a heavy stone that has sat in the same spot for generations.

One person chalks their hands, crouches down, and tries to pull the stone from grass to lap while friends shout encouragement and someone films on a phone.

Within hours the video is on Instagram. Within a few days lifters from Iceland, Scotland or the Basque Country are asking when they can travel over to try it.

It looks very 21st century. It is also one of the oldest strength practices on the island.

At the moment Ireland is in the middle of a quiet fitness boom. Gym chains are expanding, strength sports are far more visible, and conversations about lifting and training now happen in workplaces, schools and community groups.

Dr Conor Heffernan, lecturer in the Sociology of Sport at Ulster University

Dr Conor Heffernan, lecturer in the Sociology of Sport at Ulster University

We usually explain this in modern terms. We talk about health promotion, social media trends, American gym culture, high performance sport. All of that matters.

But if we stop there we miss an older and very local story that helps explain why strength training feels so natural to so many Irish people.

Across rural Ireland, especially in the west and north, communities once used specific heavy stones as informal but serious tests of strength. These were not random rocks. They were known, named and embedded in local memory.

Stone lifting is one of the oldest strength practices on the island

— Dr Conor Heffernan

At graveyards, crossroads, fairs and coastal paths young men met to see who could lift a stone from the ground, to the knee, to the waist or in rare cases right up to the chest. The heavier the stone and the higher the lift, the stronger the reputation.

The National Folklore Collection, gathered in the late 1930s, is full of these stories. Schoolchildren wrote down what older people told them about local strong men and local stones.

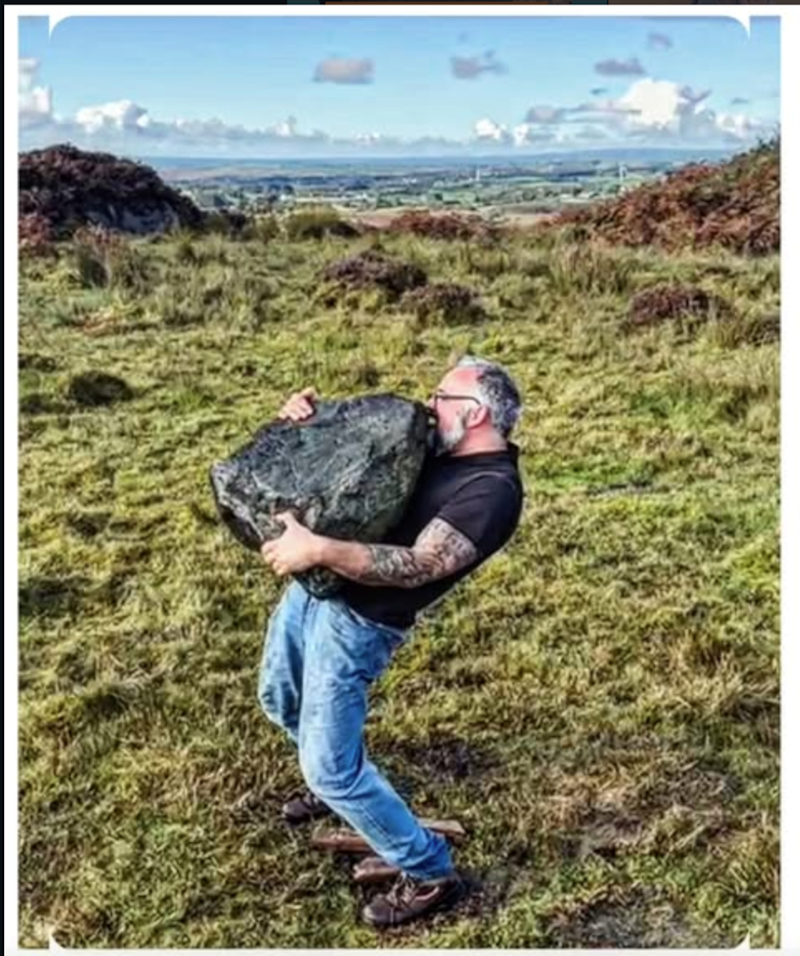

David Keohan lifting Scalp Stone in Tyrone (courtesy @Indianastones)

David Keohan lifting Scalp Stone in Tyrone (courtesy @Indianastones)

In Shanrahan graveyard in Tipperary, one stone became famous thanks to a man called Lonergan who was remembered decades later as the strongest in the parish.

In Kilkenny, children described a crossroads where young men gathered every Sunday to test themselves against particular stones that only a few could move.

In Clare and Mayo, storytellers linked the stones to the fair day, to courting, to who counted as a proper adult in the locality.

Sometimes the tone was light. Peig Sayers recalled her brother Seán, nicknamed the Pounder, who not only lifted the parish stone but stacked another on top of it just to prove the point.

In Clare and Mayo, storytellers linked the stones to the fair day, to courting, to who counted as a proper adult in the locality

In Clare and Mayo, storytellers linked the stones to the fair day, to courting, to who counted as a proper adult in the locality

Sometimes it was bleak. Liam O Flaherty’s short story The Stone follows an ageing man on the Aran Islands who becomes obsessed with lifting the same stone he raised in his youth. He manages to chest it one last time and dies from the effort. The stone, and the lift, become a way to talk about ageing, pride and mortality.

Different counties told the story in slightly different ways, but the theme was constant. Stone lifting was never only about muscle. It was about status, belonging and rivalry. Who could be trusted with hard work. Who had real potential. Which community could claim the strongest men. In some cases it even carried political and religious meaning.

One Mayo story describes a Protestant farmer who boasted that no Catholic could lift a particular stone. The local response was to find a Catholic man who not only lifted it but placed a second stone on top.

Ireland was not unique. Scotland has long celebrated its manhood stones and Highland Games. The Basque region developed a formal culture of stone lifting with standard shapes and weights and crowds who wagered on the outcome. Icelandic sagas describe fishermen tested on harbour side stones to see who was strong enough for ship work.

Novelist and short story writer Liam O’ Flaherty’s short story The Stone follows an ageing man on the Aran Islands who becomes obsessed with lifting the same stone he raised in his youth

Novelist and short story writer Liam O’ Flaherty’s short story The Stone follows an ageing man on the Aran Islands who becomes obsessed with lifting the same stone he raised in his youth

There is now a popular claim that stone lifting in Ireland was wiped out entirely by the Great Famine and by British cultural repression. It is a neat line and it fits with a wider story of things lost in the 19th century. At present, however, we simply do not have the historical evidence to back up that kind of certainty.

The Famine and later waves of migration undoubtedly emptied many rural and fishing communities. Urbanisation shifted population and work. Modern sport and physical culture provided new outlets and new ideals. All of these pressures mattered. None of them can yet be named as the single cause.

What we can say is that the practice declined, but did not vanish. In oral histories collected by contemporary lifters older people still recall men lifting particular stones in the mid 20th century. The tradition thinned out rather than being cut off in one moment.

This is why the current revival is significant. Over the past decade Waterford strongman and independent researcher David Keohan, along with a small group of equally committed lifters, has used the National Folklore Collection, old maps and local knowledge to hunt down stones described in those 1930s school copybooks.

Some, like the Sefin Stone in Derry, can be matched directly to 19th century survey notes. Others rely on field names and family memory. In both cases the work is slow but productive.

The result is that international and domestic visitors now travel to places like Gweedore, the Anne Valley walk or remote graveyards in Tipperary not only for scenery but to attempt a historically rooted test of strength. Local people share memories. Younger lifters film and post.

A small tourism economy emerges. Most importantly, communities begin to talk about their own history of strength and play rather than treating gyms and barbells as something imported from somewhere else.

Dr Conor Heffernan says lifting a heavy barbell in a gym and a rough lifting stone in a Donegal field may look worlds apart, but are part of the same story (PaulBiryukov/Getty Images)

Dr Conor Heffernan says lifting a heavy barbell in a gym and a rough lifting stone in a Donegal field may look worlds apart, but are part of the same story (PaulBiryukov/Getty Images)

Seen in this light, Ireland’s modern fitness boom looks a little different. We are not simply copying global trends. We are rediscovering, and in some cases reinventing, a much longer tradition of treating strength as a way to build identity, to mark out life stages and to argue, politely or otherwise, about who we are.

A heavy barbell in a commercial gym and a rough lifting stone in a Donegal field may look worlds apart. They are part of the same story.

Dr. Conor Heffernan is lecturer in the Sociology of Sport at Ulster University. He is the author of When Fitness Went Global (Bloomsbury 2025).