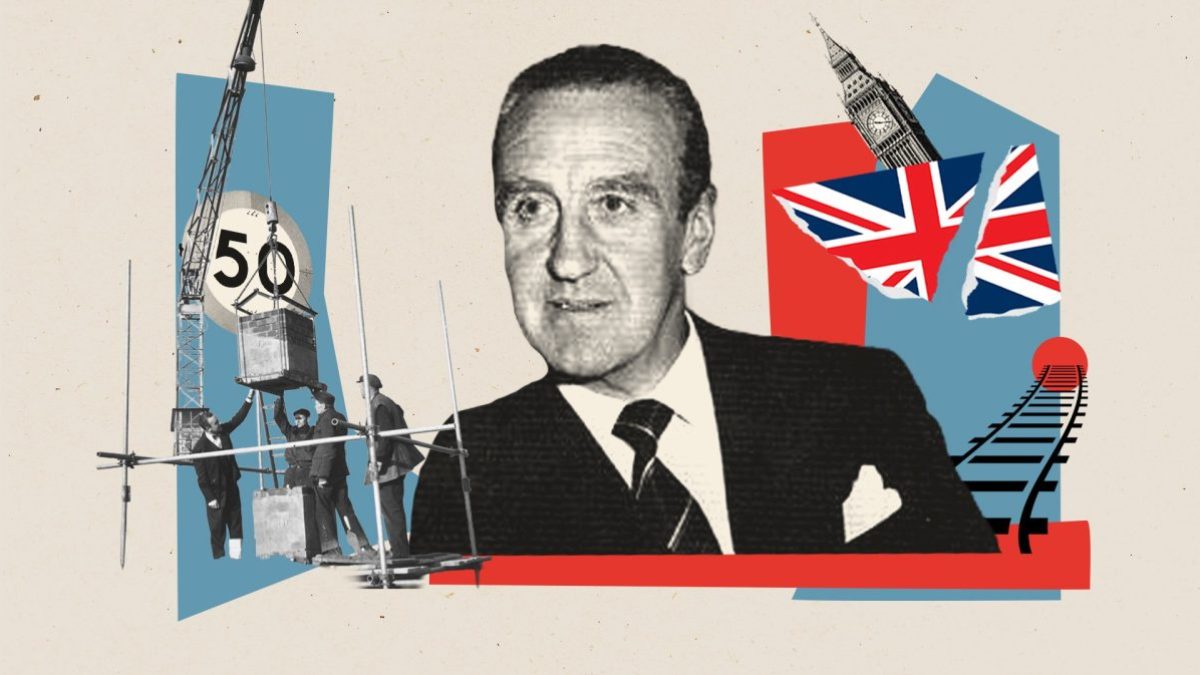

WHO BROKE BRITAIN?

The Beeching report is well known and widely hated, but the man behind it deserves our anger too

In the autumn of 1963, graffiti reading “MARPLES MUST GO” appeared on a bridge across the shiny new M1 motorway near Luton. Given that Ernest Marples was the transport minister, you might imagine that this was a reference to the hated Beeching report, published just a few months earlier, but you would be wrong: this was the most visible symptom of a viral campaign by motorists who objected to the introduction of traffic wardens and rules against drunk driving.

All of which is to say that Ernest Marples was not a cartoon villain: he achieved some genuinely good things. But in several important respects – political, moral, the interests he fought for and kowtowed to – he was both the cause and symptom of a country about to get onto the wrong track.

Alfred “Ernest” Marples was an early example of a character type then still rare: the genuinely working class and self-made Tory. (His grandfather had been gardener at Chatsworth, home to the in-laws of his rather more patrician ally Harold Macmillan.)

Born in Manchester in 1907, he attended grammar school and qualified as chartered accountant before moving to London, where he made a fortune dividing large Victorian houses into apartments. From this he built up a sizable business empire, co-founding the international engineering firm Marples Ridgway in 1948.

This expertise would prove useful when – after he was elected Tory MP for Wallasey, just across the Mersey from Liverpool, in 1945 – he was appointed Macmillan’s deputy as housing minister, charged with getting Britain building the record 300,000 new homes a year it needed after the war.

In stark contrast to certain more recent housing ministers, he succeeded. Before the 1950s were out, thanks to a stint as Postmaster General (where he oversaw the launch of premium bonds) and a talent for self publicity and eccentric dress (blue suits with orange-brown shoes, my god!), he was a familiar figure on the national stage.

And then, in 1959, Macmillan – by then Prime Minister – appointed him transport minister.

Marples’s record at transport was not all bad. Creating the motorway network, whatever you think about car culture, must surely be counted a good thing. Ditto the Road Traffic Act (1960), which introduced the MoT, yellow lines and traffic wardens.

But in 1961, he also appointed Dr Richard Beeching, an executive from manufacturing giant ICI, to work out what to do with Britain’s declining and heavily indebted network. He paid him £24,000 a year – nigh on half a million today – to do it.

Two years later, Dr Beeching produced The Reshaping of British Railways. Better known as the Beeching Report, it proposed the closure of over half Britain’s stations and 30 per cent of its track. The move was furiously opposed by everyone from poet John Betjeman to Private Eye, which published cartoons of its author with limbs lopped off. Beeching has been a hate figure ever since.

This seems at least slightly unfair. For one thing the railways really were in trouble: freight traffic was moving to lorries, more than 300 branch lines had already closed, and the cuts would continue under Labour. People loved the railways – they just didn’t use them.

But it was unfair, too, because Beeching was just doing the job he’d been given. It was Marples who had set the terms of reference, which assumed railways had to make a profit, rather than being one of those things – like schools or hospitals or, come to that, roads – which have enough spillover benefits to be worthy of state investment. It was Marples whose company had financial interests in motorway construction. (He’d handed his shares to his second wife, but come on.)

And it was Marples who decided how to implement Beeching’s recommendations. That included the failure to invest in the bus services Beeching had proposed as an alternative: in an echo of Tory policies to come, these too were closed if they couldn’t make a profit. The idea that public transport might be vital infrastructure with value outside the farebox – that it could benefit the economy by connecting people to jobs or hell just make Britain a nicer country to live in – didn’t enter into it.

In the decades since, a number of the lines closed in the 1960s have reopened, often at enormous expense. There are other signs that Marples was on the wrong side of history, too.

He commissioned Colin Buchanan’s surprising smash hit Traffic in Towns report, whose ring roads, by-passes and windswept pedestrian precincts would be blighting urban Britain for the rest of the century. He declined to introduce congestion charges, or to toll motorways. It wasn’t just that Marples was the man who accepted the inevitable decline of the railways: he simultaneously decreed the car king.

That, though, was the peak: Marples’s later career was little more than a series of scandals. An investigation of ministerial sexual ethics conducted following the Profumo affair found that he frequented prostitutes, and liked to be – this feels very Nineties – whipped while dressed in women’s clothing. That may be why he was dropped from the shadow cabinet in 1966, and never returned to high office. In February 1974 he left the Commons for the Lords.

By then, other problems were starting to mount. The tenants of his London properties were threatening legal action over his failure to deal with structural problems. He was arrested, ironically given who had introduced the rules, for drink driving. Finally, the Inland Revenue came knocking, asking when he might be paying those 30 years of back taxes due on part of his property portfolio. In 1975, he fled to Monaco before the end of the tax year. He never returned home and died in 1978.

Your next read

Lord Marples of Wallasey, as he became, is far from the worst politician Britain has known. His record contains much that is good, as well as plenty that is bad; both the decline of the railways and the rise of the car were happening anyway.

Even so, he was the one who oversaw, embraced and profited from this transition, and has spent the last six decades escaping the reputational damage by hiding behind Dr Beeching. He embedded into national policy the belief that roads provided benefits that made them always worth spending money on, but the railways amounted to little more than a cost. Looking at Britain’s transport networks in 2025, it feels a lot like this did more harm than good.

More than that, in the type of Tory he was – not just a self-made man, but a dodgy landlord and tax evader with a penchant for scandal – he was a taste of things to come. The party was always conservative, but once upon a time it had a sense of noblesse oblige. Marples was an early harbinger of the home for self-interested spivs the Conservative party would become.

Regarding that sign above the M1, incidentally, it’s worth remembering that Ernest Marples arguably did more for the motoring lobby than any transport minister before or since. And yet they hated him – for attempting to restrict their freedoms even slightly for the greater good. That, too, was a sign of things to come.