Pete and Aey Aspdin have built the rarest of grand designs. On a show that for more than a quarter-century has featured house builds overrunning, the Aspdins’ home was not only on schedule but also on budget. When Kevin McCloud, the host of Grand Design, saw it complete he said: “They landed it on time. It cost what it was going to cost . . . And the quality is beautiful. I’ve never really seen a building where you can get all three.” To the grizzled Channel 4 presenter it sounded “like sort of building heaven”.

If you are planning a project, you might wonder whether you too could reach construction nirvana. On a bright winter’s day, shortly after the episode broadcast in October, I visit the Aspdins to find out exactly how they achieved it.

Pete and Aey left Hackney, east London, for the countryside 12 years ago after they had their second child. Alice was a baby and Jo a toddler when they bought a small 500-year-old cottage in the village of Shipley, West Sussex. By 2020, with Jo in his tweens, the Aspdins needed more space.

“We couldn’t find anything around here,” says Aey, a ceramicist. “So we thought, let’s look for a piece of land.” But on every bit of land with planning permission they were “gazumped by developers”.

In 2022 they found a dilapidated three-bedroom bungalow in a nearby village and correctly surmised that they were more likely to get planning permission for a new home in its place than on a virgin field.

The completed home in Southwater, West Sussex — a Z-shaped modular masterpiece clad in scorched Scottish larch that blends seamlessly into the rural landscape

CIARAN MCCRICKARD FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

The original 1960s bungalow, nicknamed the ‘fungalow’ due to its recurring issues with damp and mould

The Aspdins bought the plot for £650,000 and moved into their “fungalow” while they planned the project. “We thought, it’s fun,” Aey says. “Then we went camping [at the end of summer] and came back and it’s like, ‘Oh, the tent was better.’”

With winter came mould, she adds. “The fungalow became a bit fungilow.”

Pete, who oversees supply chain strategy for a global healthcare company, says he wanted to “remove all of the risk that we could” from the build. “We’re working, we’ve got young kids. What we really didn’t want is a massive rollercoaster.” He knew little about building but his job meant he understood factories. That nudged them to have their home built in a factory.

Liz Truss and Kwasi Kwarteng at Berkeley’s modular plant in 2022

DYLAN MARTINEZ/PA

Doing so is not free of risk. Off-site construction has long been hailed as the future of building in Britain. Yet as the Aspdins started looking for a modular house factory, the biggest ones in the UK were closing down. L&G amassed £359 million in pre-tax losses and is shutting its giant modular factory in Yorkshire. The big housebuilder Berkeley pulled out of its modular plant in Kent, which Liz Truss, then prime minister, had visited on the day of her infamous mini-budget in 2022. Other leading players such as Ilke Homes and TopHat collapsed too.

• Kevin McCloud: ‘Britain has had a housing crisis since the 1980s’

Planning delays, construction errors with foundations and increased delivery costs had hit them. The boss of Britain’s biggest housebuilder, David Thomas of Barratt Redrow, recently told The Times that modular houses mean “you’re just shipping a lot of air around the country. It doesn’t make sense. It’s very, very expensive.”

The home has a £42,000 bespoke oak kitchen by Kenton Jones, topped with vibrant ceramic pendant lights handmade by Aey herself

CIARAN MCCRICKARD FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

However, Pete and Aey turned to Koto, which creates bespoke modular homes and cabins. Theo Dales, an architect who co-founded Koto, thinks modular construction failed when it “tried to do mass market at low cost”, whereas Koto creates “handcrafted one-off homes. We think that’s where modular construction has a lot of advantages, because it’s less stressful for the client. It’s all done off-site. It’s a much more managed and controlled process. It takes that jeopardy out of self-build.”

At first the Aspdins thought they wanted a double-storey house to take in the country views. Koto came up with a single-storey home raised up 3ft to see over the hedges. “It meant you don’t just have some rooms with long views, you have that from all of the rooms,” Dale says.

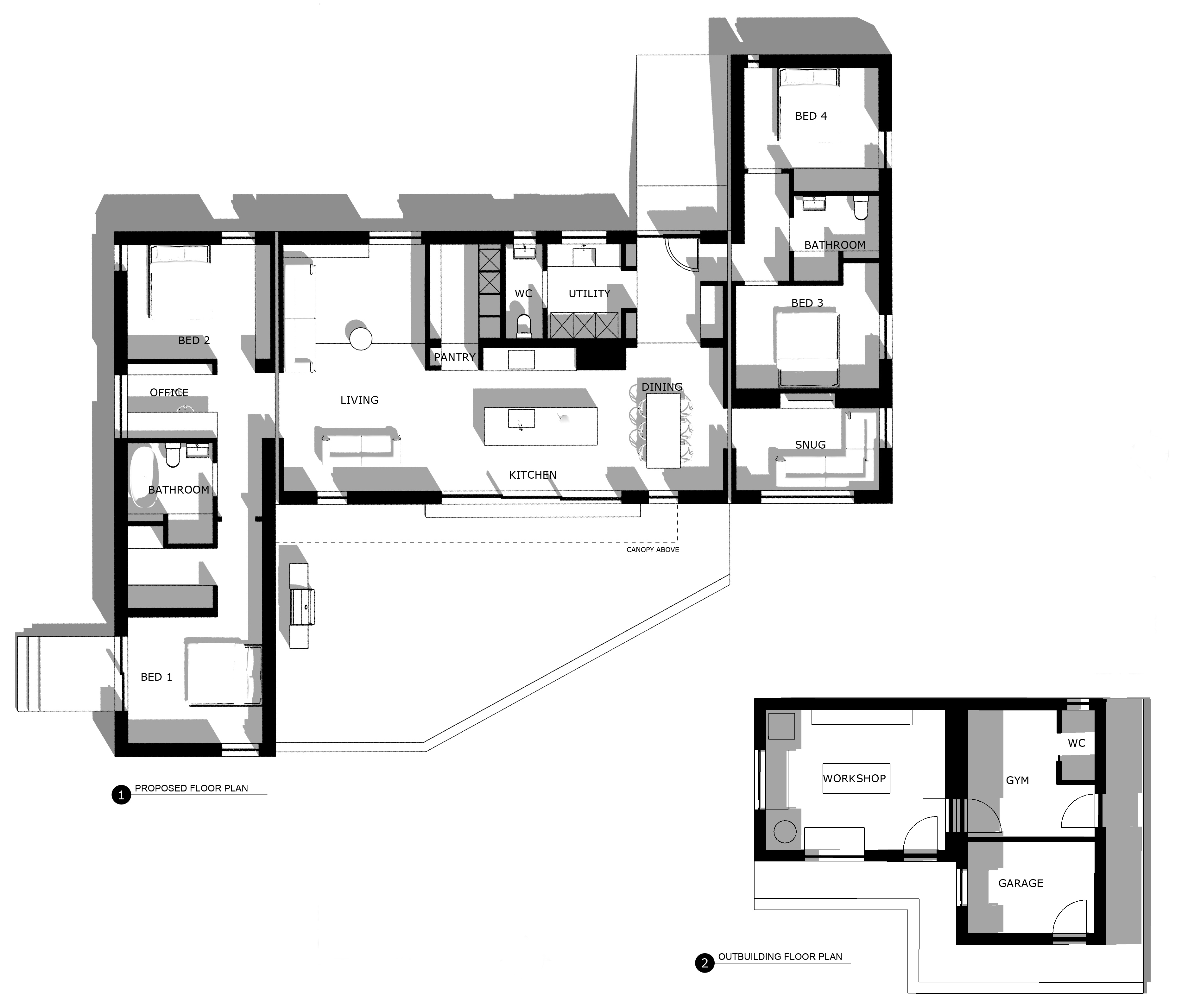

It has a Z-shaped layout around a central living space and kitchen. At each end are two bedrooms and a bathroom. Alice, 12, and Jo, 15, live on one side; their parents are on the other, alongside Pete’s office and a guest bedroom.

Glideline slim-profile triple-glazed sliding doors act as floor-to-ceiling frames for the countryside

It would be manufactured as five pods in Wales, driven 220 miles on trucks and craned into place.

The Aspdins won planning permission on their first attempt, in February 2024. Construction started in January 2025 at the Unnos Systems factory in Welshpool, where Kenton Jones’s team fitted a timber frame from locally cut Douglas fir with recycled newspaper insulation.

Then the Aspdins got a taste of modular challenges. Before any work could start on-site, they had to wait for a bat licence from Natural England. That could not be issued until last winter’s freezing weather warmed up.

The master bedroom is on one end of the house, with Aey’s pottery studio in the garden

CIARAN MCCRICKARD FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

This complicated payments because their arrears self-build mortgage released funds after each construction stage completed. The factory was already fitting their bathrooms while they waited for foundations to be finished on-site. For a few weeks Pete says he “couldn’t get any money out of the mortgage [to pay the factory]”.

His advice? “You really need to understand what information you’re going to need [to release funds for each stage]. It can leave you reliant on the goodwill of suppliers building a house for you because you can’t raise any cash to pay them.” In such a bind, it helps to work with people you get on with, he adds. “If those relationships had been difficult it would have been really painful.”

The house is made up of five separate pods, joined together on site and clad in burnt Scottish larch

CIARAN MCCRICKARD FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

In the end there were no bats. The only sign of a bat living in the old bungalow was bat droppings on one of the last roof tiles they took off, Aey says. “The ecologist stood on scaffolding and he was like, ‘Hold on a minute.’ But was there a bat? No.”

Aey cried when she first saw their house on the factory floor. “It’s all been on paper for a long time. When you actually walk into it it’s almost overwhelming,” she says.

• Hand-built Hebridean home beats rivals for Grand Designs award

Work progressed so smoothly that the Grand Designs team realised “halfway through that there wasn’t going to be this big dramatic arc”, Pete says. Contrary to other builds, which take so long that children grow up on camera, the crew filmed the Aspdins over just six months.

Craning the five pods into place took less than five hours, during which they heard “a big clunk”, Pete recalls. The Daily Mail subsequently published footage of the couple watching, it said, “in horror”. “The headline’s so different [to reality],” Aey says. “I was just, like, ‘What was that?’”

Aey’s ceramic collection is on display above their Muuto sofa

Their house had not been dropped. One 20-tonne pod, suspended from a crane, bumped the lorry that had been carrying it. Nothing was damaged — not even the meticulous herringbone bathroom tiling. It all slotted perfectly into the foundation of Techno Metal Post ground screws (chosen so “we’re not pouring tons of concrete into the ground”, Dales says). Five weeks later the family moved in, a day ahead of schedule.

As I visit, it is impossible to see where the five pods were joined. They now read as one seamless house, clad in scorched Scottish larch (IRO by BSW Timber), with an angular metal roof. The house’s zigzag footprint subtly divides the rectangular plot into public and private zones.

The table, by Another Country, is paired with Carl Hansen elbow chairs

Tucked away at the far end, between a hammock pergola and a veg patch, is Aey’s pottery studio, where she makes vibrant tableware and lighting, including the pendants above their kitchen island (aeyglom.com). The handmade oak kitchen, which cost £42,000, is by Kenton Jones.

The Glideline slim sliding doors are triple-glazed and the MVHR freshens the air and prevents mould in the airtight house. A rainwater harvesting system feeds the lavatories, while an air source heat pump supplies hot water and heating.

On social media the odd detractor accused the couple of “shocking eco-washing” for “demolishing an existing house to build an eco house”. To this Aey says: “I don’t think we could save the bungalow.”

Before the broadcast Grand Designs’ welfare team warned the family not to look at comments and to contact them if gawkers turned up on their doorstep. But their phones pinged with warmth, Pete says. “We had people in the supermarket going, ‘Congratulations on your house.’”

The build cost, including planning, professional fees and full fit-out, totalled “just over £800,000”, Pete says. “It worked out. And it was largely stress free.”

In an unexpected downside, the lack of jeopardy made their episode rather boring. As a relative who works in TV told Dales: “Really cool project, but it’s awful television.”