Light is usually described using quantum mechanics when phenomena like entanglement enter the picture. But a new paper shows that light’s polarization and entanglement obey a simple identity – written as P² + K² = 1 – that holds for any light field.

That single relation makes the result strikingly general, across experimental setups and dimensions.

The work comes from Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, and links wave descriptions of light to mechanical ideas taught in introductory physics courses.

The study links measurable light intensity to familiar mechanical ideas such as center of mass and moment of inertia, using a geometric map that treats optical weights like point masses.

What the identity says

The identity relates polarization, the direction of light’s electric field oscillation, and a second property called entanglement, which captures how different parts of a field behave together.

When polarization grows toward a single, favored direction, entanglement fades accordingly.

Conversely, when entanglement rises toward its maximum, polarization necessarily drops, so the two always balance.

The study was led by Xiaofeng Qian, assistant professor of physics at Stevens Institute of Technology.

Professor Qian’s research focuses on optical coherence, classical-quantum connections, and practical routes to measure elusive properties with sturdy instruments.

Math behind the behavior of light

Mathematically, the relation uses a coherence matrix – a compact table of correlations between field components. Its eigenvalues act like weights that determine both polarization and entanglement in one picture.

Those weights also trace a path that reveals how the two properties share strength without exceeding the fixed total set by the identity.

In two-dimensional beams, the entanglement measure reduces to concurrence, a number that quantifies pairwise linkage in the simplest quantum systems. This has a standard closed form for two qubits.

That special case nestles cleanly inside the broader result while keeping the same intuitive trade-off with polarization.

A classical theorem meets light

The bridge to mechanics uses the Huygens-Steiner theorem, a formula that links moments of inertia for parallel rotation axes, to reinterpret optical numbers as distances between mass-based geometric points.

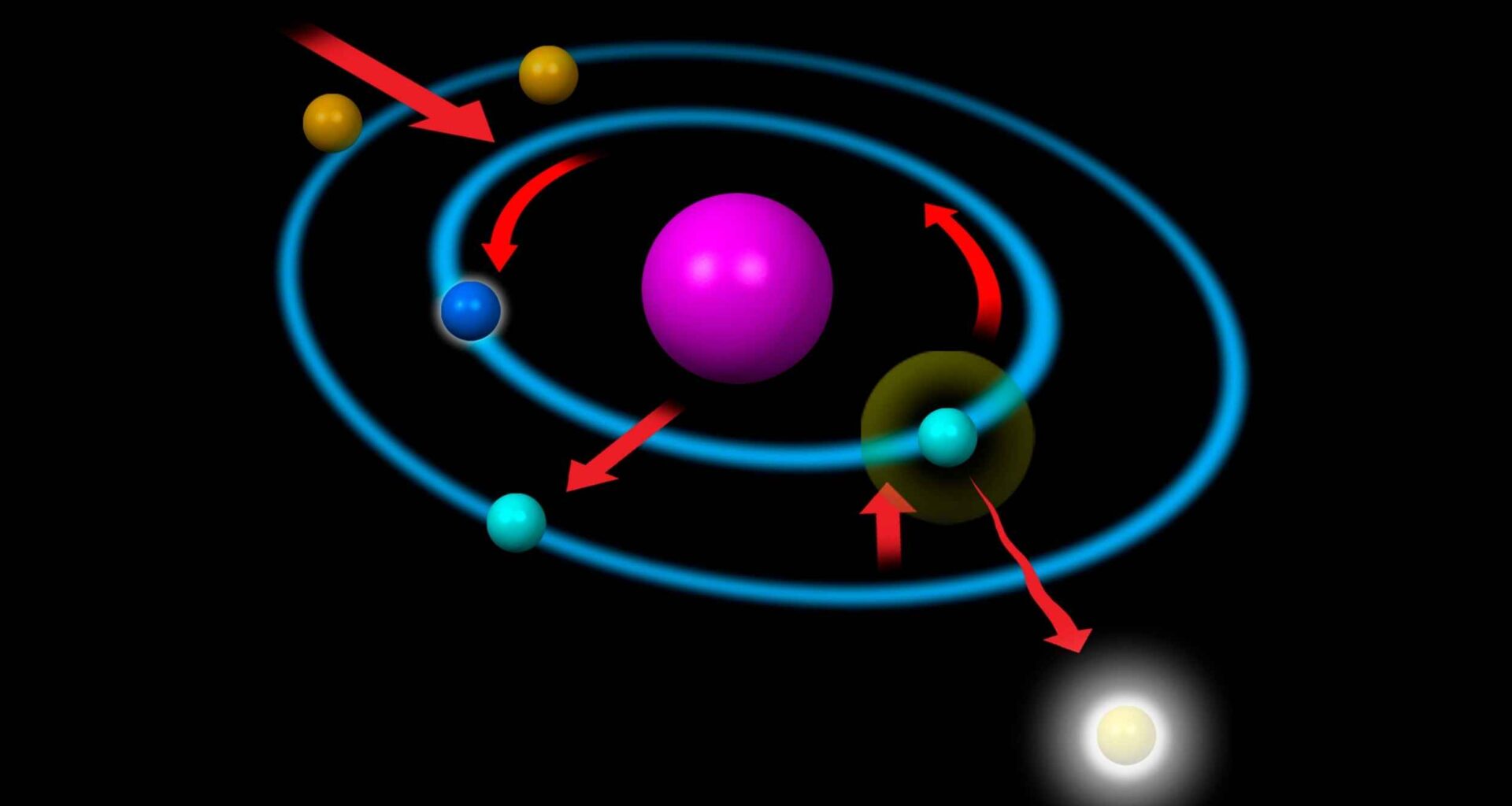

The team mapped the matrix eigenvalues to three point masses at the corners of a regular triangle, then tracked how the center of mass shifts as polarization and entanglement trade places.

This mapping uses barycentric coordinates. These are coordinates defined by triangle corner weights rather than a standard grid, which offer a direct way to compute centers and distances.

The straight line from the triangle’s center to the mass center measures polarization, and a perpendicular line to the unit circle measures entanglement, so the two lengths satisfy a simple Pythagorean sum.

“This is a well-established mechanical theorem that explains the workings of physical systems like clocks or prosthetic limbs. But we were able to show that it can offer new insights into how light works, too,” explained Qian.

Implications for measurements

In practice, entanglement – nonrandom correlations shared across a system – often hides behind complex protocols that demand calibration-heavy optical benches and carefully stabilized interferometers.

The new identity lets researchers infer entanglement levels from polarization measurements alone, turning a familiar observable into a reliable dial for estimating otherwise opaque features.

Because polarization is resistant to modest noise and easy to measure across many beams, it can stand in when direct tests of entanglement are impractical in teaching labs or resource-limited facilities.

That substitution honors limits set by the identity, which prevents overreach by forcing polarization and entanglement to remain within a fixed circle of possibilities.

From equations to tests

Early experiments have already explored the connection by measuring polarization and entanglement alongside two-mass mechanical analogs.

These tests check whether the predicted balances appear outside chalkboard calculations.

Preliminary reports describe a quantitative match in laboratory conditions, which hints that this unusual optics-mechanics link can be engineered for sensing and education.

Future research directions

The experts showed that the same balancing act holds for higher numbers of components, not just three-dimensional fields, by extending their definitions to any number of structural modes.

That makes the relation a versatile yardstick for complex fields shaped by time, space, and internal degrees of freedom – particularly in the gray area where classical and quantum pictures overlap.

Equations do not replace experiments, but they can reveal smarter ways to measure what matters, saving time and reducing experimental overhead.

It may seem surprising that ideas rooted in centuries-old mechanics can illuminate modern optical behavior, but the connection becomes intuitive once the pieces are set side by side.

The result is a reminder that even familiar tools can still uncover new insight when researchers return to them with careful questions.

The study is published in the journal Physical Review Research.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–