A. littoralis. Credit: [email protected]

A. littoralis. Credit: [email protected]

In coastal communities across Brazil, people have used the plant Alternanthera littoralis—sometimes referred to locally as Joseph’s Coat—to treat inflammation and infections.

Now a team of Brazilian scientists has put that tradition through a modern stress test: standardized extracts, controlled dosing, and multiple animal models designed to mimic acute joint inflammation. In mice, the extract reduced swelling and pain-related sensitivity, while also changing markers tied to inflammation.

The work, published in the Journal of Ethnopharmacology, does not mean people should start self-medicating with a beach plant. But it does add something folk medicine rarely gets: a growing stack of quantitative evidence, as well as a careful look at safety, before anyone talks about capsules, tinctures, or clinic visits.

Evidence From Animal Models

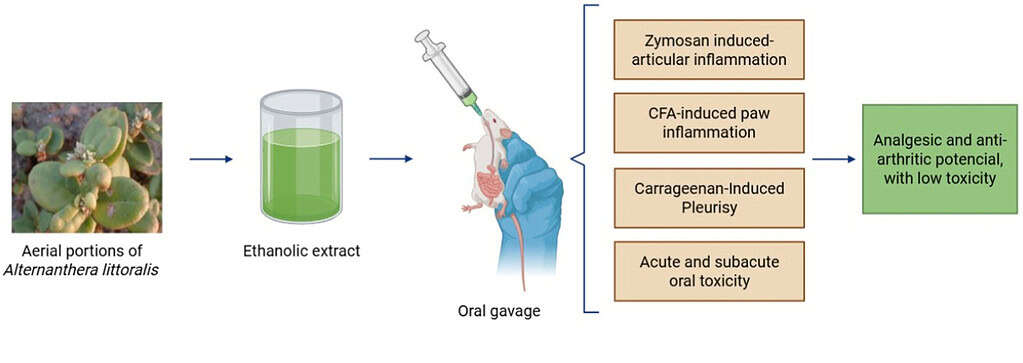

The research brought together scientists from three Brazilian universities. Working in the lab, they made an alcohol-based extract from the parts of the plant that grow above ground, then tested it in mice using standard methods that researchers commonly use to study inflammation and arthritis.

In one set of experiments, the team triggered inflammation in a mouse’s knee joint using a substance that reliably activates the immune system. Mice that received the plant extract developed less swelling and reacted less strongly to pain. Fewer immune cells flooded into the joint, a sign that inflammation had eased.

In a second set of tests, the researchers focused on inflammatory pain in the paw. They measured how sensitive the animals were to pressure and cold, how much swelling developed, and how strongly the immune system responded at a chemical level. Again, mice treated with the extract showed less pain and lower signs of immune activity.

Taken together, the results followed a consistent pattern. “In the experimental models, we observed reduced edema, improved joint parameters, and modulation of inflammatory mediators, suggesting antioxidant and tissue-protective actions,” said Arielle Cristina Arena, a biologist at São Paulo State University who oversaw the safety testing.

Where These Results Fit

Credit: Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2026).

Credit: Journal of Ethnopharmacology (2026).

Osteoarthritis affects tens of millions of people around the world, and many continue to struggle even when they follow standard medical advice. Exercise, weight management, and physiotherapy can help, but for many patients they are not enough to control pain and stiffness.

Options for pain relief are also limited. Available drugs often provide only short-term benefit and may cause side effects with long-term use, leaving a large number of people living with persistent joint pain.

These gaps explain why scientists keep revisiting traditional plants. Many modern medicines started as natural compounds, then moved through a long pipeline: identification, isolation, dosing, safety testing, and—most importantly—human trials.

This new study sits near the front of that pipeline. It tests an extract, not a purified drug. However, it does not model the slow, years-long cartilage breakdown that drives osteoarthritis in humans. Instead, it focuses on induced inflammation in mice.

Even so, the researchers’ approach moves the plant toward a higher bar: results that can be measured and compared. In the study itself, the authors conclude that the extract showed “significant anti-inflammatory, analgesic, and anti-arthritic effects in multiple in vivo models, with comparable efficacy to prednisolone in several parameters.”

Safety Comes First

Effects on pain and swelling tell only part of the story. Researchers also tested whether the extract disrupted basic body functions, a key requirement for any substance intended for long-term use.

“Finally, we performed the toxicological analyses under my coordination,” Arena said. In acute tests, mice received doses up to 2000 mg/kg with no deaths and no obvious signs of toxicity, a result consistent with a “low toxicity” classification under OECD guidance described in the paper.

The more telling test came from repeated dosing over 28 days. The researchers reported no major changes in body weight, food and water intake, organ weights, or blood counts. But they did see a consistent increase in ALT, a liver enzyme that can rise when liver cells are stressed or damaged.

The authors note that the ALT increase was not accompanied by other abnormal biochemical markers, and they call for longer-term studies and tissue-level examinations to clarify the risk.