For decades, scientists believed that ammonites, spiral-shelled marine creatures, were wiped out alongside the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. But a new study published in Scientific Reports challenges this timeline, revealing that some ammonites survived long after the asteroid impact. The study raises a new question: if they escaped Earth’s most infamous mass extinction, what ultimately caused their final disappearance?

A Legacy of Survival Before a Sudden End

Ammonites were among the most successful and resilient marine species in Earth’s history. They thrived in the oceans for over 340 million years, evolving through multiple forms and surviving three major mass extinctions before the Cretaceous–Paleogene (K–Pg) event. Their fossils, abundant and beautifully coiled, are found worldwide, from England’s Jurassic Coast to the cliffs of Morocco.

Because ammonites disappear from the fossil record around the same time as the non-avian dinosaurs, scientists long assumed they died in the immediate aftermath of the asteroid impact. The widely accepted theory held that the impact caused rapid ocean acidification and food chain collapse, leading to their extinction. But new fossil discoveries challenge that assumption.

The Denmark Discovery That Rewrites the Story

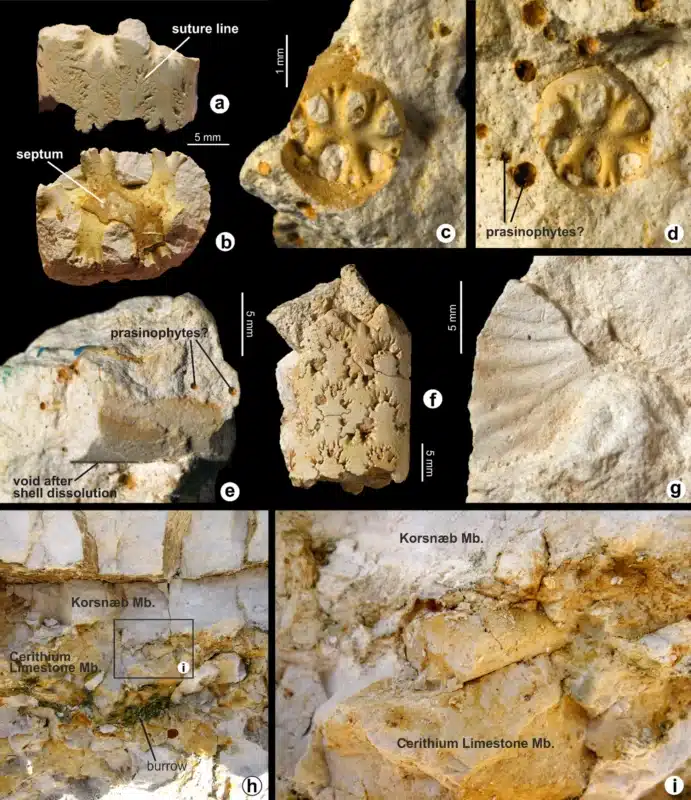

The new evidence comes from Stevns Klint, Denmark, a site recognized by UNESCO for its unique preservation of both pre- and post-extinction fossils. In a recent paper published in Scientific Reports, Professor Marcin Machalski of the Polish Academy of Sciences and his colleagues reported finding ten ammonite fossils in limestone layers dating from the early Paleogene period, tens of thousands of years after the asteroid hit.

These fossils belonged to three known genera, Hoploscaphites, Baculites, and Fresvillia. Crucially, most of the specimens showed no signs of being reburied from older layers. In one example, researchers found a preserved void where the shell had dissolved, a strong indication that it fossilized in place rather than being moved from earlier strata. Most intriguing was the Fresvillia genus, previously unseen in the region during the late Cretaceous, suggesting it had spread after the extinction event.

The presence of these ammonites in such well-dated geological layers suggests that they survived for up to 200,000 years after the initial catastrophe, a much longer timespan than previously believed.

Dead Clade Walking: A Delayed Extinction

If ammonites didn’t die immediately from the asteroid’s effects, why did they disappear shortly afterward? The answer may lie in a phenomenon known as “Dead Clade Walking,” a term describing species that survive an extinction event only to die out soon after due to long-term stresses.

While the post-impact ocean likely returned to chemical stability within tens of thousands of years, ecosystems remained deeply disrupted. Ammonites, especially those that relied on plankton-based food webs, may have struggled to find enough food or suitable reproductive conditions. Even if they physically survived the impact, their genetic diversity and ecological resilience may have been too compromised to support recovery.

This scenario contrasts with their distant relatives, the nautiloids, which somehow managed to survive and still swim today. Nautiloids had deeper living ranges, slower reproductive cycles, and different ecological strategies, factors that may have given them an edge in the unstable world after the impact.

Why the Fossil Record Misled Us

The belief that ammonites perished alongside the dinosaurs has endured for decades, partly because Paleogene ammonite fossils are rare and often misinterpreted. Until now, such fossils were dismissed as re-deposited Cretaceous specimens, shifted by erosion or geological activity. But the findings at Stevns Klint are remarkably well-preserved and clearly located in early Paleogene sediment, making them difficult to dismiss as mere anomalies.

This discovery highlights how our understanding of extinction events can be shaped, and sometimes distorted, by incomplete or misinterpreted fossil records. It’s a reminder that even widely accepted scientific timelines can be revised with new evidence and careful analysis.