NASA’s Perseverance rover has spotted a desk-sized rock, nicknamed Phippsaksla, on Mars that looks suspiciously like an iron-rich meteorite.

Roughly 31 inches wide (80 centimeters) wide, the lonely boulder sits in the Vernodden area just beyond Jezero Crater.

The work was led by Candice Bedford, a research scientist at Purdue University, whose studies focus on Martian rocks.

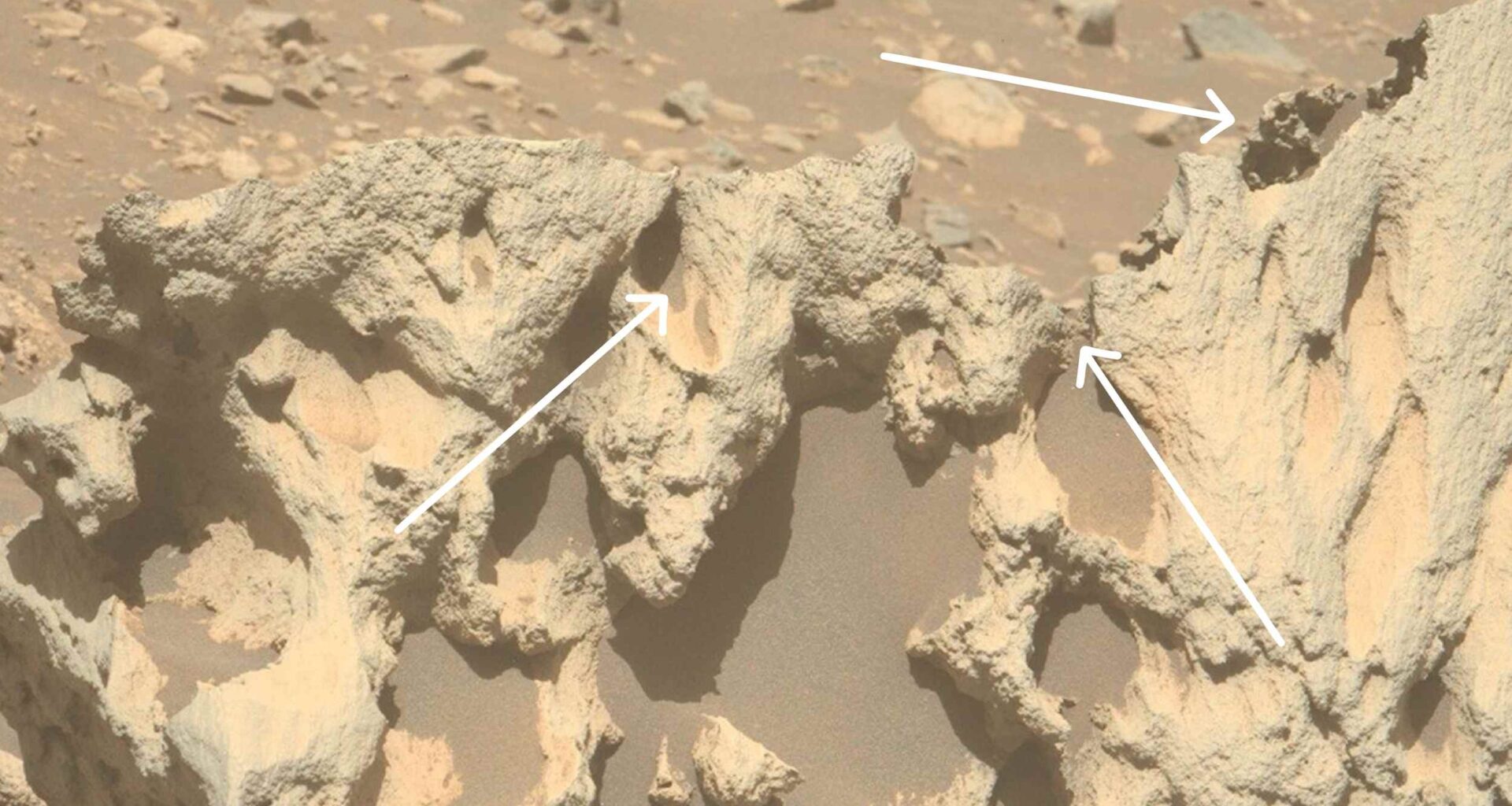

The unusual Phippsaksla rock has a sculpted shape and raised position that make it stand out from the flatter, broken rocks carpeting the crater rim.

Initial analysis showed that Phippsaksla holds iron and nickel, matching an iron-nickel meteorite, a metal-rich rock from space.

Because it rests on fractured, impact-formed bedrock outside Jezero Crater, the rock may record how older collisions reshaped that landscape.

Meet the Mars rover that found it

Perseverance has spent nearly five years exploring Jezero Crater, an ancient lake basin where water once pooled and left layered sediments.

The rover’s main job is collecting rock and dust for return to Earth, guided by a recent study that mapped their context.

Finding a stray metal-rich rock along that route reminds scientists that Mars still holds surprises even in heavily studied terrain.

The Vernodden outcrop lies on the rim where impacts fractured bedrock, solid stone beneath loose soil, and left scattered blocks.

Iron and nickel in Phippsaksla

On both Mars and Earth, rocks loaded with iron and nickel usually trace back to the shattered cores of large asteroids.

These metal-rich meteorites formed when early planetesimals, small worlds that built planets, melted inside and separated heavy metals from lighter rock.

If Phippsaksla is one of these fragments, it offers a sample of deep asteroid material without launching a new mission.

Mars’ thin atmosphere and dry surface mean such metal-rich rocks can sit for ages with relatively little rusting or erosion.

What meteorites on Mars reveal

As they travel through space, metal bodies record hits from cosmic rays, high-energy particles that stream from the sun and stars.

By measuring changes inside such meteorites, researchers estimate how long they wandered between planets and when they landed on a world.

Back on Earth, scientists have identified hundreds of Martian meteorites, then studied their chemistry to compare with rocks seen directly on Mars.

A confirmed meteorite sitting at Vernodden would flip that story, giving researchers a chunk of solar system metal that landed on Mars instead of Earth.

Late to the meteorite party

Spirit and Opportunity each spotted metal-rich meteorites during their long treks, proving Mars could preserve wandering space rocks for years.

In Gale Crater, the Curiosity rover examined Lebanon, a roughly 2-yard-wide (1.8-meter-wide) metal meteorite that gleamed against the surrounding dusty surface.

Later, Curiosity rolled past Cacao, an iron-rich meteorite with a 1 foot (30 centimeter) width that showed similar metallic composition.

Given that history, scientists wondered why Perseverance had not yet logged its own metal meteorite while crossing Jezero’s floor and delta.

Examining Phippsaksla rock

Perseverance first spotted Phippsaksla with Mastcam-Z, twin-zoom cameras that provide detailed color views, as they scanned distant terrain for interesting textures.

The rover then used SuperCam, a laser-based instrument that analyzes rock chemistry from several yards away, to examine the metal-rich target.

By vaporizing tiny spots on the surface, this system reads plasma with spectroscopy, a technique that identifies elements from their light.

The pattern of peaks in that data helps distinguish a metal meteorite from basaltic lavas that also contain iron.

Shaped by time and thin air

Up close, Phippsaksla shows deep pits and grooves that likely formed as softer material eroded away under the harsh Martian environment.

Processes called space weathering, surface changes driven by micrometeorite impacts and radiation, can darken and smooth metal surfaces over millions of years.

Because Mars has very little air and almost no liquid water at the surface, corrosion there progresses differently than on Earth.

By comparing Phippsaksla’s texture with weathering seen on metal meteorites, scientists hope to estimate how long it has rested on that ridge.

Clues about ancient Mars

A meteorite on Jezero’s rim would carry material from beyond the crater’s watershed, adding an external datapoint to Mars’ own geologic record.

If scientists can date the meteorite and rocks beneath it, they refine impact chronology, timelines of when collisions struck Mars.

Its mixture might resemble asteroids sampled by missions like Hayabusa2 and OSIRIS-REx, letting researchers connect findings with pieces stored in Earth laboratories.

Placing an ancient lakebed and a metal visitor within one region gives scientists a fuller picture of Jezero’s long history.

Why this find matters

For future crews living on Mars, metal-rich meteorites like Phippsaksla could someday provide handy sources of iron for tools or shielding.

Because their chemistry differs so strongly from native rocks, they might be easier to spot, characterize, and safely process using robotic equipment.

Mapping how many metal chunks sit on different Martian surfaces helps engineers gauge landing hazards and durability needs for long-term infrastructure.

Data from Phippsaksla will feed models of object impacts on Mars, information that planners use when choosing sites for bases and sample depots.

Lessons from Phippsaksla rock

For now, the team treats Phippsaksla as a candidate meteorite, and plans follow-up observations to confirm its chemistry lacks Martian ingredients.

Engineers can command the rover’s arm to brush, drill, or image the rock, giving instruments a view of its structure.

Whether Phippsaksla proves to be meteoritic metal or an unusual Martian rock, the investigation adds another chapter to Perseverance’s story of Jezero.

To observers on Earth, that lone boulder shows that even after decades of robotic exploration, Mars still holds startling surprises.

The study is published in a press release by NASA.

Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/ASU

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–