A new NASA timelapse was two and a half decades in the making. What makes the timelapse of the Kepler Supernova Remnant even more spectacular is that it wasn’t captured on Earth, but in space. The supernova remnant is a whopping 17,000 light-years away from Earth, or over 99 quadrillion miles.

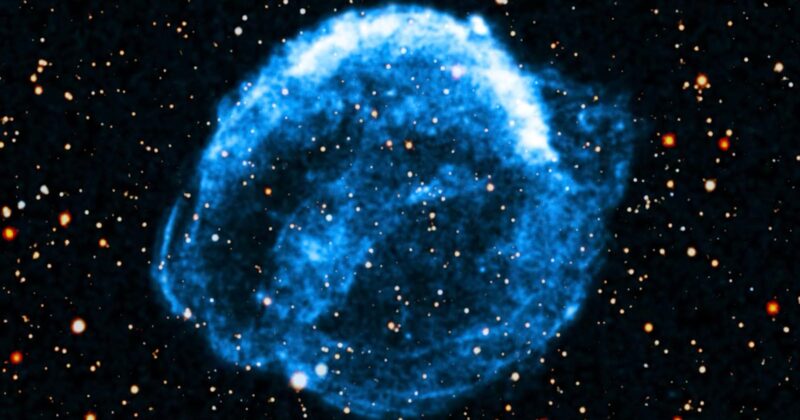

The timelapse relies heavily on X-ray imaging data from NASA’s space-based Chandra X-ray Observatory, and also includes optical imaging from Pan-STARRS, a panoramic survey telescope in Hawaii. Chandra is no stranger to long-term observations and checking back in on the same cosmic object over time, but this is the longest-spanning timelapse the venerable telescope has ever done. In the timelapse below, the X-ray data is blue.

Chandra captured images of the Kepler Supernova Remnant, first discovered in the night sky by astronomers in 1604, in 2000, 2004, 2006, 2014, and most recently, in 2025.

Supernova remnants are particularly fascinating subjects for astronomers and astrophysicists. They are the debris fields that supernovae leave behind when they explode, and supernova remnants are often aglow in X-ray light because their materials were superheated to millions of degrees in the supernova explosion. In the case of the Kepler Supernova Remnant, although astronomers didn’t realize it back in the early 17th century, it is a Type Ia supernova. It was once a white dwarf star that exceeded its critical mass and exploded. Scientists use these types of supernova remnants to measure the rate of expansion of the Universe.

The rate of expansion of this particular supernova remnant is a key component of the timelapse endeavor. By capturing images of the supernova remnant for 25 years, scientists can measure how different parts of the supernova remnant move and at what rates. The fastest parts of the remnant are traveling at roughly 2% the speed of light, or 13.8 million miles per hour, NASA explains. This region is seen near the bottom of the timelapse.

Meanwhile, the slowest region, near the top of the image, is traveling at a measly 0.5% the speed of light, or four million miles per hour. What a slowpoke.

NASA explains that the significant speed difference across different regions of the supernova remnant is due to variations in density, which itself offers key insights into how the star exploded.

“Supernova explosions and the elements they hurl into space are the lifeblood of new stars and planets,” says Brian Williams of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. Williams is the principal investigator of Chandra’s new observations of Kepler. “Understanding exactly how they behave is crucial to knowing our cosmic history.”

“The plot of Kepler’s story is just now beginning to unfold,” says Jessye Gassel, George Mason University graduate student and leader on the timelapse work. “It’s remarkable that we can watch as these remains from this shattered star crash into material already thrown out into space.”

Image credits: X-ray: NASA/CXC/SAO; Optical: Pan-STARRS