Pink diamonds are rare. Very rare. Their origins? Still not entirely understood. Most are small. Most are tightly held by private collectors or sold through commercial channels before scientists ever see them. What they can tell us about the Earth’s ancient interior often vanishes the moment they’re cut.

Now, a newly uncovered rough diamond, found in Botswana, offers something different. Not just in size. Not just in colour. But in the clarity of what it captures: two different geological histories, frozen in a single crystal.

One half pink. The other, perfectly colourless.

A Natural Record of Deep Mantle Conditions

Weighing 37.41 carats, the diamond was recovered from the Karowe mine and sent for analysis in Gaborone. Scientists at the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) determined it to be a Type IIa diamond, a rare classification defined by extremely low nitrogen levels and notable for chemical purity. This purity makes the visual contrast between the two halves especially distinct.

What sets this specimen apart, researchers observed, is its likely two-stage growth sequence. The pink half appears to have formed first, then transformed structurally under high geological stress. The colourless section seems to have developed later, without deformation.

The pink hue itself is not caused by trace elements, unlike yellow or blue diamonds. It results from plastic deformation, where the crystal lattice bends under pressure. That shift alters how light passes through the diamond. If the stress is too strong, the stone turns brown. Too little, and it stays colourless.

In some diamonds, colour appears in thin bands called lamellae, which mark ancient fault lines inside the crystal. In this Botswana specimen, however, the transition is clean and planar. That allows a rare chance to compare structural conditions across clearly separated zones within the same crystal.

Kimberlite and the Ascent to the Surface

The diamond originated more than 160 kilometres underground, in the upper mantle, where high heat and pressure allow carbon to crystallise. To reach the surface without degrading into graphite, it needed rapid transport. That journey was powered by kimberlite, a volatile-rich igneous rock known for carrying diamonds to the surface.

Kimberlite forms during deep-source volcanic eruptions that penetrate ancient continental crust. These eruptions cool into vertical structures called kimberlite pipes, which often host commercial diamond deposits. As described by Encyclopedia Britannica, kimberlite is a dark, heavy, magnesium-rich rock that typically contains olivine, phlogopite, garnet, and other high-pressure minerals.

The Karowe mine, which sits on stable, billion-year-old cratonic crust, is known for exceptional finds. In 2024, it produced the 2,488-carat Motswedi diamond, one of the largest ever discovered.

Modern processing techniques at Karowe are designed to protect large crystals from damage during recovery. This allowed the 37-carat diamond to arrive intact at the lab, retaining its internal features for scientific inspection.

Supercontinent Breakup and Pink Diamond Origins

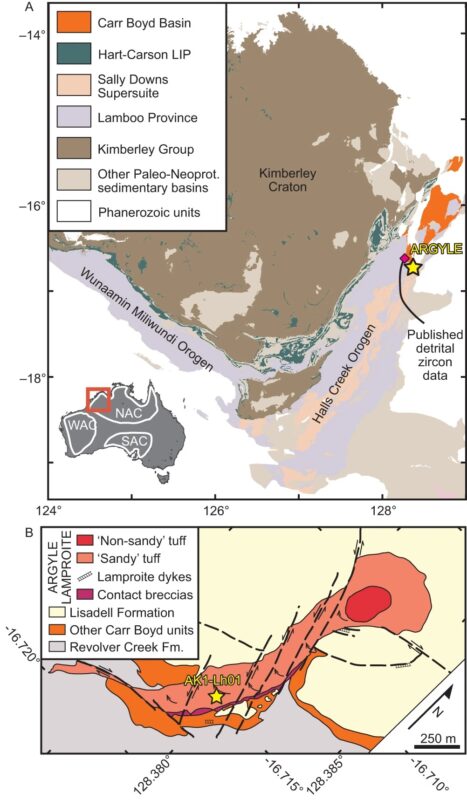

Researchers studying the origin of pink diamonds are increasingly linking their formation to tectonic forces rather than surface chemistry. A study published in Nature Communications examined the geological context of the Argyle diamond deposit in Western Australia. Argyle produced over 90 percent of the world’s known pink diamonds before its closure in 2020.

The study found that Argyle’s host rock, a volcanic material called lamproite, was emplaced between 1311 and 1257 million years ago, during the breakup of the supercontinent Nuna. This event created deep rift zones in the Earth’s crust, such as the Halls Creek Orogen near the Kimberley Craton, where Argyle is located.

By using uranium-lead (U-Pb) dating methods on minerals including zircon, apatite, and titanite, the researchers concluded that continental extension during this period generated the structural strain responsible for pink colouration. “The age of 1257 ±15 Ma records in a most conservative sense a minimum emplacement age for the Argyle diatreme complex,” the study noted.

Although geographically distinct, the Botswana diamond shows a similar two-phase growth pattern. The alignment of features across both cases supports the view that tectonic deformation during major rifting events may be essential to the formation of pink diamonds.

Structural Insights and Implications for Research

The Botswana diamond is undergoing detailed, non-destructive testing to map internal structures and colour zones. These include spectroscopic imaging and lattice analysis to determine the specific defects—known as defect centres—that produce its pink hue. Both halves of the stone will be examined independently to assess how physical conditions varied during growth.

GIA researchers noted that the stone allows for a rare comparative study of two distinct growth environments within a single crystal. This kind of structure, sharply divided and undeformed, provides physical insight into how pressure, temperature, and mantle dynamics influence diamond formation.

Before any cutting takes place, experts will evaluate whether the boundary between the pink and colourless zones can be preserved. Commercially, the pink section is likely more valuable, but scientifically, the full crystal offers a richer dataset.