Another big boxing film is here. This time Prince Naseem Hamed gets the Rocky treatment. We know this because Giant is produced by Rocky, aka Sylvester Stallone, and the poster describes it as “The UK’s answer to Rocky”. Whether it can replicate its stateside cousin by winning the Oscar for best picture depends on whether the suits prefer Ariana Grande or the one about Shakespeare’s son.

Hamed’s story is unquestionably filmic and Amir El-Masry has the looks to play him, with Pierce Brosnan alongside as Brendan Ingle, the Irish trainer who made the Prince a king and then, inevitably, fell out with him. It is easy to see why boxing appeals to Hollywood. A protagonist from a difficult background overcomes huge obstacles and gets the girl. Stallone’s eureka moment was having Rocky lose, heroically of course, to Apollo Creed, and still get the girl.

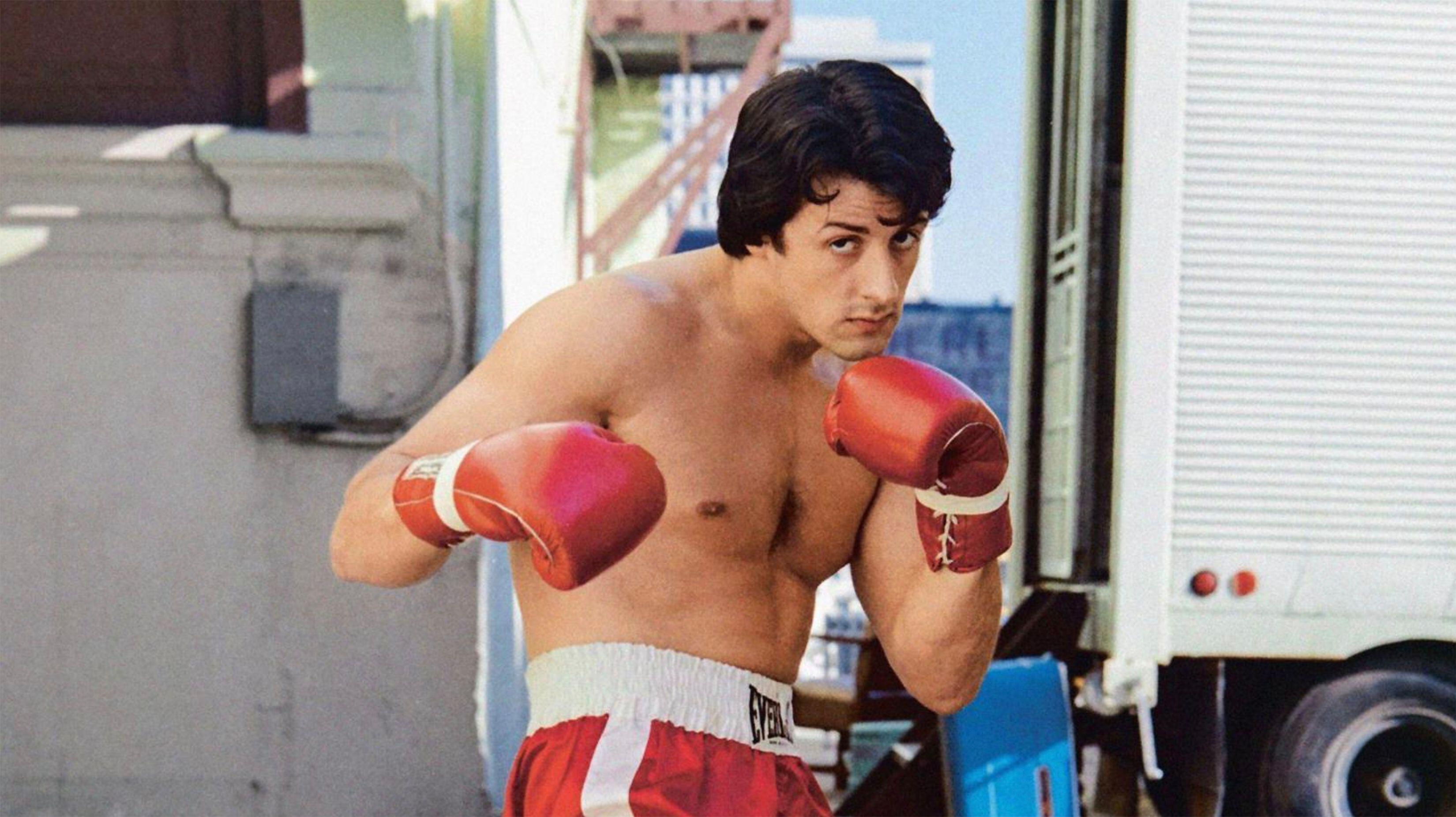

Sylvester Stallone as Rocky Balboa in Rocky, which won best picture at the 1977 Oscars

ALAMY

You can’t get this drama from football. There are too many team-mates for a start and going a goal down is not the same as having your face bashed in. And modern film-makers may balk at the idea proposed by Escape to Victory that defeating Nazi Germany was contingent on sticking Sly in goal and getting Russell Osman to shore up the back four.

Boxing wins at the cinema. And so, to mark Naz’s relaunch, here is a list of the best boxing flicks, in ascending order. Documentaries are ruled out and there are some notable omissions. The Hurricane does not do justice to the Rubin Carter story, Jawbone has a great Weller soundtrack but is a bit slight, and Million Dollar Baby is not even Clint Eastwood’s best fight film; that’s Every Which Way But Loose, in which he is overshadowed by an orangutan.

10) Cinderella Man (2005) — star Russell Crowe

With a plot so over the top it makes Rocky look like reality TV, James J Braddock is the Depression-era fall guy who comes back from 18 losses in 36 bouts to see off flash heavyweight champion Max Baer, who lights cigars with thousand-dollar bills. It is a true underdog yarn with bells on, and no less satisfying for the inevitability of the conclusion.

I once interviewed Braddock’s nephew, then 86, who was in the Long Island City Bowl in 1935. “I’ve got a picture taken at the fight with my uncle,” Joseph Mallon said. “At one point, when he got hit by Baer, my grandfather was all for getting in the ring himself. Jimmy was on welfare when he won the title, but he made sure he paid it all back. He was an honourable guy. Afterwards it went mad. A lot of people made money out of him and he became a hero. He had a bar in Times Square for a while, but people would drink for free, so that didn’t last long.”

Two years later, Braddock would lose his title to an up-and-coming Joe Louis. “It’s like someone jammed a light-bulb in your face and busted it,” was his description of Louis’ power, but he had done a shrewd deal to take 10 per cent of the new champ’s earnings for the next decade. Footnote: After being dropped as an expert adviser, Joe Bugner described Crowe as a “gutless worm”.

9) Journeyman (2017) — Paddy Considine

This is grim, gritty and a bit great. It involves post-fight brain surgery, suicidal ideation and domestic violence before boxing rescues Considine. Boxing has always appealed to writers because of its grubby romance and its status as both a trap and refuge. With Considine and Jodie Whittaker setting the perfect tone, this is one of the best broken-man-tries-to-fix-himself boxing flicks. Footnote: UFC champion Michael Bisping retired after watching the film, saying he did not want to become another Matty Burton.

8) Somebody Up There Likes Me (1956) — Paul Newman

This is a fairly straightforward run through the life of Rocky Graziano, a juvenile delinquent turned middleweight champion in the 1940s. It builds towards the climactic title fight with Tony Zale and has enough sleaze — blackmail, fixed fight etc — to please the theatre-going audience of the time.

It has its flaws. I’m a paid-up fan of Paul Newman, who interviewed Graziano several times in preparation, but this is one of his first starring roles and the over-acting is hammy at times. The role had been due to go to James Dean, but he died in a car crash before filming began. Steve McQueen has an uncredited bit-part. Footnote: Zale was due to play himself in the fight but was dropped after refusing to pull his punches.

7) The Fighter (2010) — Mark Wahlberg

Although it sticks to the narrative arc of lose-struggle-win, The Fighter is really a story about brothers. Micky Ward, a real survivor of numerous Fight of the Year contenders, has to deal with his cocaine addict half-brother Dicky Eklund, as well as self-doubt and opponents. It is raised above most boxing movies by Christian Bale’s performance as Dicky, Ward’s deluded trainer, while Ward’s reckless courage makes him analogous to Rocky Balboa.

The epilogue states Micky retired and married Charlene while Dicky is a local legend, but the truth was not so glossy. Ward developed symptoms of brain disease CTE (chronic traumatic encephalopathy) and has agreed to donate his brain for research after being approached by Chris Nowinski, the former WWE wrestler who set up the Boston University CTE Center. Nowinski lamented: “We tried to tell his story when he pledged his brain, that Micky, the toughest guy ever, was telling you to stop doing this [head sparring]. Nobody cared.”

6) The Set-Up (1949) — Robert Ryan

The only boxing flick in the list based on a narrative poem. Ryan is “Stoker”, another journeyman whose wife wants him to give up. His manager is so convinced of his waning ability that he takes mob money for a dive, but does not bother to inform his man. Stoker finds out about the set-up in the fourth round, rallies and wins, and then duly gets his hands broken with a brick in a back alley. His wife finds him and, knowing he can never fight again, conjures up a classic film noir pay-off: “You won tonight. We both won tonight.”

The poet behind The Set-Up quickly distanced himself from the film. Joseph Moncure March said: “I was really disgusted to find that the hero of the picture was no longer a Negro fighter — they had turned him into a white man. The whole point of the narrative had been tossed out the window. Ah, Hollywood.”

The studio, RKO, claimed they had no black actors under contract, but the whitewashing of boxing in the 1940s was a reflection of a segregated society. The film critic Christina Newland pointed out that during the 11 years of Joe Louis’ reign as heavyweight champion, no major studio released a boxing film with a black protagonist.

5) Creed (2015) — Michael B Jordan

Or Rocky 7 to some. Creed is surprisingly good, as the son of Apollo Creed recruits Rocky, still Stallone of course, with the aim of fighting Tony Bellew at Goodison Park. It sounds like something from a Jake Paul fever dream, but Stallone’s understated performance mines the nostalgia and old-pro tropes to good effect. Footnote: The epic fight scene was filmed in one continuous shot.

4) Raging Bull (1980) — Robert De Niro

This has film critics salivating in a way sport normally only prompts when pundits discuss wall passes at Manchester City. Middleweight champ Jake LaMotta’s story is brutal, visceral and unflinching, and has to be on the list, but it is not the best in my opinion. As a study of jealousy, domestic abuse and toxic masculinity, it is peerless, but it is unremittingly cold. De Niro got the Oscar, but there’s no light here, just shady men. Footnote: De Niro gained 60lb to portray the older LaMotta. Crowe lost 40lb to play Braddock.

3) Requiem for a Heavyweight (1962) — Anthony Quinn

Fascinating just for its mesmerising fictional bout between Mountain Rivera (Quinn) and a young Cassius Clay that plays out even before the titles have finished, this is another film that features the has-been, the fix (an obsession in older fight films) and mobsters looking for their money back. It’s fair to say this film hates boxing and is essentially about a fighter’s twisted relationship with his manager, even to the point of suffering a humiliating wrestling finale to save his skin. Footnote: Quinn made this when “Lawrence of Arabia” stalled shooting for two months.

2) Rocky (1976) — Sylvester Stallone

Yes, it is corny, schmaltzy and now looks like a tick-box exercise (sagacious trainer, training montage, uplifting ending), but it does everything to such a high standard and is part of modern culture. Where it works more than many boxing films is Stallone clearly likes the sport, or at least has empathy for the people in it, and so there is an authenticity to it (Rocky’s training run was done through Philadelphia without public knowledge, so when a punter throws an orange to him it is entirely spontaneous).

There are lots of good lines too. Burgess Meredith tells him: “You’re gonna eat lightnin’ and crap thunder.” Good enough to see off All the President’s Men and Taxi Driver at the 1977 Oscars anyway. Footnote: the great Scottish fighter Ken Buchanan claimed Stallone “owes me” for the scene when he has his trainer cut his swollen eyelid with a razor blade. That happened for real in Buchanan’s epic title bout with Ismael Laguna in 1971.

1) Fat City (1972) — Stacy Keach, Jeff Bridges

This John Huston box-office flop is bleak but dazzling. One washed-up fighter and one kid going nowhere try to keep hold of dreams amid mounting evidence that there is no hope. When Keach finally gets a win, you see him begin to wonder what it is all about.

Stacy Keach, left, as Billy Tully and Susan Tyrrell as Oma Lee Greer

ALAMY

It’s a dead-end world of losers, like a Bruce Springsteen song with lots of minor chords but shiny shorts. It’s the best boxing film because it nails the sadness like no other. Ultimately, Fat City knows that all life’s strugglers can do is go another round. It’s anti-Rocky. Footnote: Huston was a talented amateur boxer in his teens until a broken nose ended his career. In 2023 his grandson, Jack, made the lovingly-shot but clichéd Day Of The Fight.