It floats, it drifts, it doesn’t break down. Plastic in the ocean is everywhere, but now it’s doing more than polluting. It’s becoming something else.

In the middle of the Pacific Ocean, where no islands or coastlines exist, small marine animals are settling. They’re not just riding the currents. They’re building communities. Some are growing, others are reproducing. All of them are doing it on plastic.

![The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is the largest of the five plastic accumulation zones in the world’s... [+] oceans.](https://imageio.forbes.com/blogs-images/scottsnowden/files/2019/05/GPGP2.jpg?format=jpg&width=1440) The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is the largest of the five plastic accumulation zones in the world’s oceans. Credit: The Ocean Cleanup

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch is the largest of the five plastic accumulation zones in the world’s oceans. Credit: The Ocean Cleanup

This wasn’t supposed to happen. The open ocean has always been too harsh for coastal life. No rocks, no sea floor, no anchor. But floating trash is changing that. It’s providing a surface. A home.

Researchers are beginning to see this plastic debris not just as waste, but as a new kind of habitat. What it means for marine life, and for the ocean as a whole, is only starting to come into focus.

Plastic Isn’t Just Floating, It’s Hosting Life

A team of scientists recently studied 105 pieces of large plastic debris collected from the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre. That’s the swirling ocean current system where the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is located. This is the zone where plastic tends to gather and stay.

The researchers found that 98 percent of the items had marine life attached. In total, they identified 46 different types of small animals, including barnacles, crabs, amphipods, and anemones. Of those species, 37 are usually found near coastlines. That means animals that typically live on rocks, piers, or the seabed are now surviving far from shore.

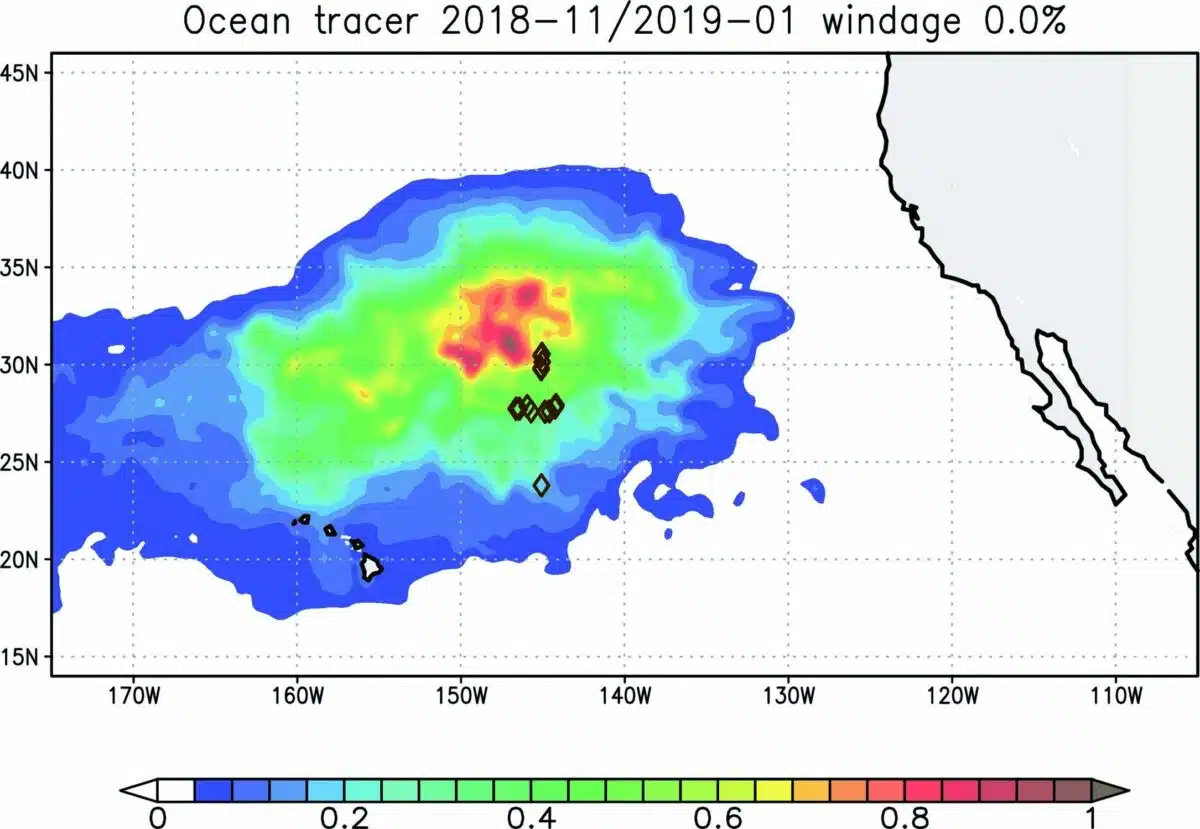

Modeled concentration of floating plastic debris in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (2018–2019), with sampling locations marked in black diamonds. Warmer colors indicate higher debris density. The core of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is clearly visible between Hawaii and California. Credit: Nature Ecology & Evolution

Modeled concentration of floating plastic debris in the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre (2018–2019), with sampling locations marked in black diamonds. Warmer colors indicate higher debris density. The core of the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is clearly visible between Hawaii and California. Credit: Nature Ecology & Evolution

These findings are part of a study published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, which analysed how both coastal and open-ocean species have formed lasting communities on plastic debris in the gyre.

Many of the species weren’t just surviving. They were reproducing. Some carried eggs. Others showed signs of different growth stages. In some cases, scientists saw young and adult animals living together on the same plastic object.

The most heavily colonised items were ropes and nets. Their tangled shapes provided more space to hold on and more protection from waves and predators. These artificial surfaces are now acting like miniature islands for species that were once thought unable to survive in open water.

Why Plastic Stays in the Gyre for Years

The North Pacific Subtropical Gyre is a slow-moving loop of ocean currents. It stretches between Asia, North America, and Hawaii. Because of the way the currents flow, anything floating into this area tends to stay there. That includes plastic.

This system, known for its role in creating oceanic “garbage patches,” is explained in more detail on the North Pacific Gyre Wikipedia page, which describes how stable circulation traps debris in its center.

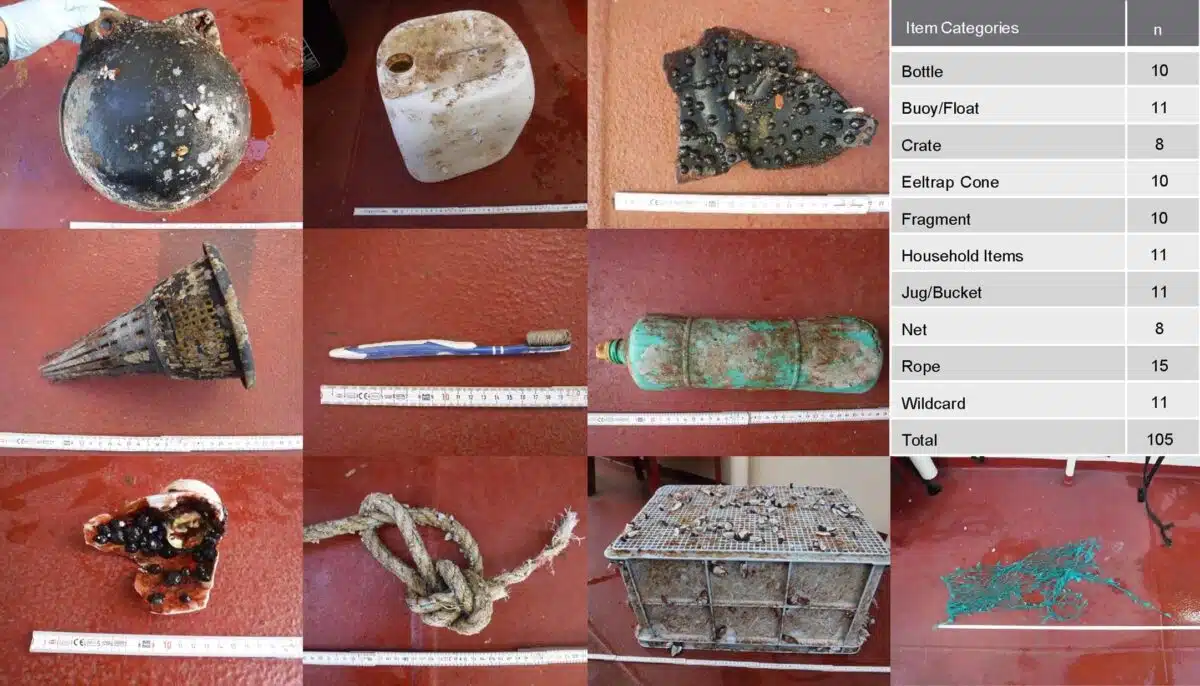

Examples of plastic debris collected from the North Pacific Garbage Patch, showing heavy biofouling by marine life. Items included nets, ropes, buckets, and household objects. The table shows the number of samples by category, totalling 105 items. Credit: Nature Ecology & Evolution

Examples of plastic debris collected from the North Pacific Garbage Patch, showing heavy biofouling by marine life. Items included nets, ropes, buckets, and household objects. The table shows the number of samples by category, totalling 105 items. Credit: Nature Ecology & Evolution

Over time, floating debris builds up in the middle of the gyre. This creates the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, which now contains an estimated 1.8 trillion pieces of plastic, based on data from the environmental initiative The Ocean Cleanup. Most of these pieces are small, but more than 90 percent of the total mass comes from large items like fishing gear and containers.

Unlike natural materials like driftwood or seaweed, plastic doesn’t rot or sink quickly. It can float for years. This gives animals plenty of time to find it, attach to it, and build small ecosystems on it.

Because the gyre moves slowly and keeps plastic in circulation, it gives these new marine communities a chance to grow in one place, even in the middle of the ocean.

How a Tsunami Revealed the Survival Potential

After the 2011 tsunami in Japan, millions of tons of debris were swept into the Pacific. That debris included boats, docks, plastics, and other materials, as documented on the Wikipedia page on the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami. In the years that followed, scientists discovered many of those objects still carried coastal marine species alive when they reached places like Hawaii and North America.

More than 280 different species made that journey. Some survived on the floating debris for as long as six years. This showed that coastal life, given the right conditions, could tolerate life at sea.

A follow-up article from Earth.com explains how many of the same organisms first observed on tsunami debris are now being found living on plastics in the garbage patch. These include crabs, sea anemones, hydroids, and others that normally depend on fixed surfaces close to shore.

Their ability to reproduce asexually, feed in place, and anchor to debris gives them a clear advantage when it comes to long-term survival in the open ocean.