The frozen edges of Antarctica are less stable than they appear. Beneath the wide, seemingly immovable shelves of ice, the ocean is at work. Currents carry heat into hidden cavities, silently reshaping the foundation of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet. Most of what lies below the ice remains out of reach. Or at least, it did.

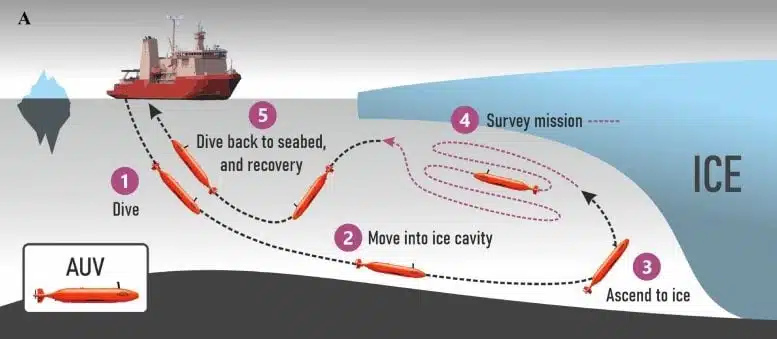

In recent years, scientists have begun to penetrate these spaces using advanced autonomous vehicles. These underwater robots are deployed beneath the shelves to map terrain, measure melt, and study how seawater and glacial ice interact in places satellites cannot see. One such mission, conducted beneath the Dotson Ice Shelf, returned with the most detailed images yet of an Antarctic glacier’s underside.

Then the robot disappeared. But, before contact was lost, it had recorded unexpected structures beneath the ice.

Breakthrough Maps From Beneath the Ice

The mission was part of the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC), a joint research programme between British and American scientists. Their aim: understand how West Antarctica’s ice shelves respond to changing ocean temperatures. In 2022, researchers launched Ran, an autonomous underwater vehicle developed by Swedish scientists, to explore the cavity beneath the Dotson Ice Shelf.

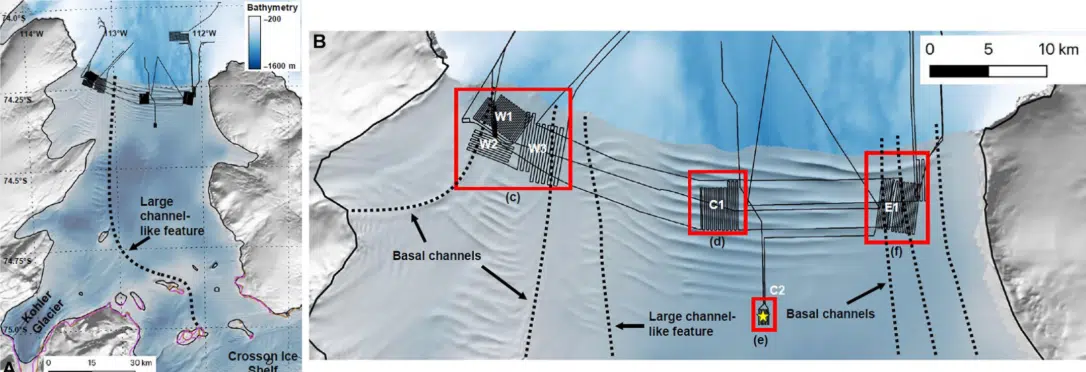

The vehicle travelled more than 1,000 kilometres during a 27-day survey, capturing high-resolution sonar images of over 140 square kilometres of sub-ice terrain. This part of the ice sheet had never been mapped in such detail.

The autonomous underwater vehicle Ran was programmed to perform missions under the ice shelf. An advanced multibeam sonar system was used to map the underside of the ice at a distance of about 50 meters. Credit: Anna Wåhlin/Science Advances

The autonomous underwater vehicle Ran was programmed to perform missions under the ice shelf. An advanced multibeam sonar system was used to map the underside of the ice at a distance of about 50 meters. Credit: Anna Wåhlin/Science Advances

“We were able to get high-resolution maps of the ice underside. It’s a bit like seeing the back of the Moon for the first time,” said Anna Wåhlin, professor of oceanography at the University of Gothenburg, in a statement published by the British Antarctic Survey.

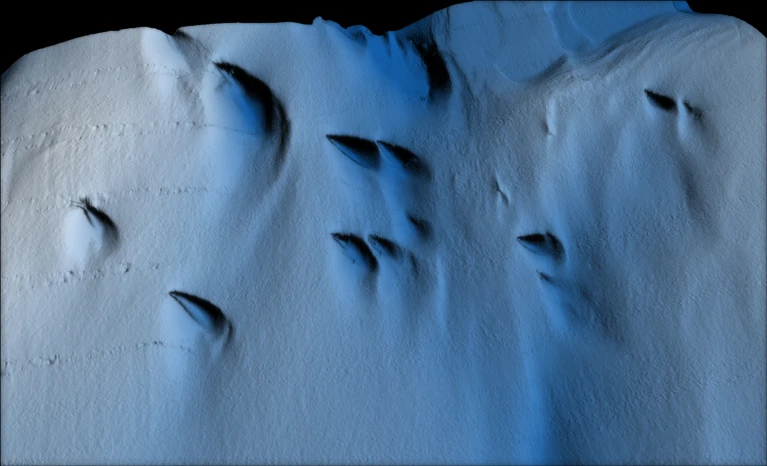

According to a peer-reviewed study published in Science Advances, the underside of the shelf revealed complex terrain: terraced ledges, teardrop-shaped pits, and long melt channels carved by warm water. The structures point to localised zones of erosion, likely shaped by the intrusion of Circumpolar Deep Water, a relatively warm ocean current moving along the continental shelf.

Patterns of Melting More Complex Than Expected

The Dotson Ice Shelf is thinning, but not evenly. Sonar data confirmed that melting is concentrated in specific areas, not across the entire shelf. Two deep cavities beneath the western flank were found to be linked by narrow channels that help move warm water efficiently into the ice base.

This uneven pattern supports earlier findings from satellite altimetry and climate models, which showed significant melt along the western edge of Dotson. These concentrated flows of heat explain why some regions of the shelf are retreating faster than others.

A visualization of the underside of Dotson Ice Shelf showing mysterious tear drop shaped areas of melting. Credit: Filip Stedt/University of Gothenburg

A visualization of the underside of Dotson Ice Shelf showing mysterious tear drop shaped areas of melting. Credit: Filip Stedt/University of Gothenburg

“The maps that Ran produced represent a huge progress in our understanding of Antarctica’s ice shelves,” said Karen Alley, a glaciologist at the University of Manitoba. “We’ve had hints of how complex ice-shelf bases are, but Ran uncovered a more extensive and complete picture than ever before.”

Data collected from ocean sensors and satellites indicate that the Dotson Ice Shelf has lost nearly 390 gigatonnes of ice over the past 20 years. As the shelf thins, its ability to resist the movement of grounded inland glaciers declines, increasing the potential for accelerated ice flow into the ocean.

Longstanding fractures, some visible since the 1990s, were found to widen at their base due to concentrated turbulence. These act as entry points for warm water and can accelerate hidden ice loss, a process not fully accounted for in many ice sheet models.

Disappearance During 2024 Expedition

In early 2024, researchers returned to Dotson to repeat parts of the mission and assess changes in the underside structure. During a follow-up dive, Ran entered the sub-ice cavity for a scheduled 24-hour survey. It failed to return.

Without a live data link—radio signals cannot penetrate several hundred metres of solid ice—the team could not monitor the vehicle’s progress. Post-mission searches yielded no acoustic signals or debris. Ran’s final location remains unknown.

Dotson Ice Shelf. (A and B) Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica mosaic. Credit: Science Advances

Dotson Ice Shelf. (A and B) Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica mosaic. Credit: Science Advances

“Although we got valuable data back, we did not get all we had hoped for,” Wåhlin told British Antarctic Survey News. The cause of the loss is unclear, though experts have cited possible mechanical failure or a collision with an underwater ridge.

Despite the setback, scientists say the sonar data collected during the initial survey continues to improve understanding of basal melt and ice-ocean interaction. The disappearance has also prompted new discussions on the design and resilience of autonomous systems operating in extreme environments.

What This Means for Sea Level Rise

Ice shelves like Dotson serve as structural supports for larger glacier systems. When they weaken, they allow grounded ice to accelerate toward the ocean. Over time, this leads to rising sea levels globally.

Melting beneath Dotson has already contributed approximately 0.02 inches to sea level rise between 1979 and 2017, according to estimates published in Science Advances. Total ice loss from West Antarctica during that period accounts for over 0.5 inches, a figure that continues to rise with accelerating melt.

US research ship Nathaniel B. Palmer at the ice front of Thwaites Glacier, taken by drone. Credit Alex Mazur

US research ship Nathaniel B. Palmer at the ice front of Thwaites Glacier, taken by drone. Credit Alex Mazur

Findings from Ran offer strong evidence that melt is not a slow, even process. Instead, warm water targets specific features—fractures, deep cavities, and channels—leading to more rapid degradation than most global models currently reflect.