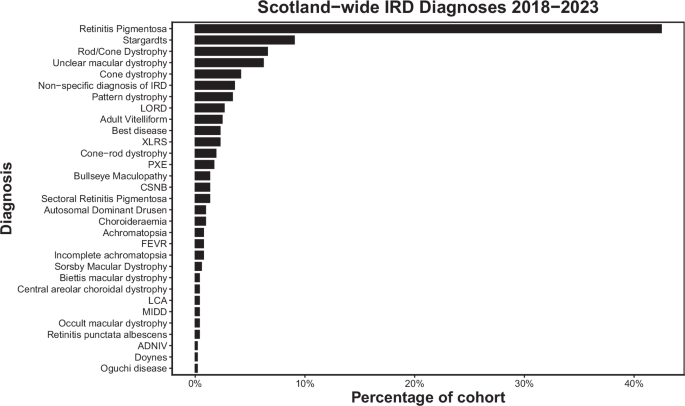

This study presents a description of inherited retinal disorders in Scotland over a 5-year period. The most common initial testing strategy was a retinal gene panel, but this varied by region, with some more likely to attempt targeted testing in the first instance. Volume of genetic testing varied by region; a reflection of their respective populations. The most common clinical diagnoses were Retinitis pigmentosa and Stargardt disease, with the most common RP syndrome being Usher’s disease. The most common genes identified were ABCA4, USH2A, RDS/PRPH2, RS1, RHO and C1QTNF.

Previous work describes a range of molecular diagnosis rates in IRD. Khan et al. reported a molecular diagnosis rate of 40% in patients with IRD, and Ellingford described a 50% success rate [7, 16]. This is lower than the 67.4% reported in our study, but comparison of results is limited as their work related to the use of a 105 gene panel, rather than the 176 panel. Sheck et al.’s more recent work describes IRD molecular diagnosis rates in Moorfields between 2016 and 2018 using the 176 gene panel and reported a higher rate of 59.4% [8]. Further, they observed that a younger age at testing and certain diseases were more likely to result in a molecular diagnosis. In this study, diseases with a strong phenotype:genotype relationship initially underwent more targeted gene screening, and were thus not included for analysis. Our data includes analysis of targeted gene testing which had a slightly higher molecular diagnosis rate, increasing the overall molecular diagnosis rate in our cohort. Indeed, when analysed separately, our 176 gene panel results broadly agree, at 65.2%.

Previous work has demonstrated higher rates of molecular diagnosis in those presenting at a younger age. Taylor et al. report 78.8% of 85 cases under the age of 16 had a molecular diagnosis during a period of time when both 105 and 176 retinal gene panels were used [17]. Similarly, Sheck et al. reported 81.8% received a molecular diagnosis if <10 years old [8]. Our results show a similar trend, with 79.3% obtaining molecular diagnosis if a clinical diagnosis is made within first 2 decades. The reasons for this are likely multifactorial but could reflect that mutations with high functional consequences are more likely to be exonic and so easier to detect. Conversely, it is suggested that less pathogenic mutations (causing later onset disease) may be under less selective pressure and therefore of higher prevalence, making them harder to detect bioinformatically [8].

Regarding the most common clinical diagnoses, our work agrees closely with that reported from the My Retina Tracker initiative, a database of over 15,000 patients across the globe with IRDs. Similar to our work, they report that the most common diagnosis is Retinitis pigmentosa, followed by Stargardt disease and Usher syndrome [18]

Regarding the relative frequency of mutation in individual genes, our Scottish results are largely in keeping with the Global Retinal Inherited Disease dataset, who report that the most common mutation in the literature is ABCA4, followed by USH2A [19], with RHO and PRPH2 also common. This is similarly reflected in work performed by Moorfields, but perhaps unsurprisingly, given the founder mutation originated in East Lothian [20], our Scottish cohort contains significantly more C1QTNF5 mutations than national global studies [12].

The proportion of RP that is syndromic has previously been reported to range from 20-30% [21]. Our results broadly agree with this figure, but we report a slightly lower rate of syndromic RP at 15.5%, though rising to 19.4% (35/180) among RP cases with a molecular diagnosis. Our results are in keeping with other studies, whereby syndromic RP is most commonly diagnosed in patients with Usher syndrome, followed by Bardet-Beidl, then Refsum disease [22, 23].

Few previous studies have reported real world duration of genetic panel tests, particularly in the context of IRDs. Some studies have reported time to a molecular diagnosis of 12 to 21 weeks [24, 25]. The American Academy of Ophthalmology refers to the context of ‘clinically relevant’ turnaround time, noting that speed and cost increase in tandem and that 6 months would be a reasonable target [26]. Our mean turnaround time of 5.6 months is within this notional target, though the reasons for some regions taking longer will be reviewed in further work. When NHS England transitioned to offering whole genome sequencing (WGS) as part of routine care for monogenic disease, NHS Scotland instead opted to develop a targeted exome for testing IRDs [27]. Future work will aim to analyse the impact on speed and rate of diagnosis.

In our Scottish cohort, over 30% did not receive a molecular diagnosis. Whilst some of this missing heritability may be due to as yet undiscovered causal genes, it is known that adoption of WGS into IRD screening, with the resulting capture of 5’ prime and intronic sequences of known genes, can increase the proportion of cases obtaining a molecular diagnosis by 10-15% [9, 28, 29]. A national transition to this testing paradigm, matching NHS England, has significant potential for benefit. This has already been recognised; in their “Genomic Medicine Strategy 2024–2029” the Scottish Government articulate their ambition to update and develop their testing strategies to include WGS, and ensure that associated genomic data is incorporated into national datasets [30]. Aligned WGS approaches would also help to standardise IRD testing pathways, leading to reduced regional variation and improved time-to-diagnosis, with this work providing a useful baseline with which to measure improvement.

This study provides a comprehensive assessment of the ophthalmic genetics service across Scotland over a 5-year period, involving a large number of patients across all of the main ophthalmic centres. However, we are limited in the completeness of our assessment by the number of patients still to be seen in genetics clinic or awaiting their genetics results. Furthermore, as inclusion in the study was contingent on referral and clinic attendance in a tertiary centre, there may be a degree of under-representation of certain communities or districts if they are underserved or under-referred by community ophthalmic teams, As the period studied includes the COVID-19 era, there may be some artefactually reduced activity in some regions during this time. Similarly due to the data storage methods on the EPR used, we may be subject to a degree of false-negative results, whereby results have been received but not yet uploaded to the system.