“Programmer by day, photographer by weekend” Cristian Băluță could not find the precise camera he wanted in the market, so he made it himself. Băluță expertly took the internal components from the Panasonic Lumix G9 II Micro Four Thirds camera and put them inside a Leica M replica body he made. It was a labor of love, and while the photographer admits the result isn’t necessarily the dream camera he imagined, the project is incredible.

The “Leica G9 II,” as Băluță calls it, required a lot of very careful hardware and software engineering. The programmer/photographer has a rich history of working with electronics and has also grown frustrated with the state of Micro Four Thirds cameras.

“Then there was this frustration with MFT losing its identity and companies officially killing their compact lineups and rangefinder style cameras. OM System eventually released OM-3 shortly after I started building this but it was not a rangefinder style nor very compact,” Băluță writes, admitting that his new camera is not necessarily very compact either, it is roughly the size of a full-frame Leica M rangefinder, which Băluță says is “the absolute minimum” he could do.

As for why he opted to transform a Panasonic Lumix G9 II, a relatively recent camera released in late 2023, Băluță explains that the G9 II is “the most capable” Micro Four Thirds camera out there. It has the best resolution, good phase-detect autofocus, dual card slots, and, perhaps as important as anything else, works very well with the Panasonic Leica lenses Băluță loves, like the excellent Panasonic Leica DG Summilux 15mm f/1.7 ASPH. Panasonic and Leica, a match made in photography heaven.

Băluță had just a few requirements for his Leica G9 II build, but they were far from simple. He wanted the camera to look like a Leica M rangefinder, with a high-quality look and feel, no visible screws, and a lens mount as centered as possible. The photographer also wanted his camera to have only the most essential buttons and controls, nothing he didn’t personally need for his photography.

Băluță didn’t already own a Lumix G9 II, either, so he needed to buy a used one for around 1,000 euros for the project. It proved quite the gamble, because he says he hadn’t fully researched the camera’s internal design.

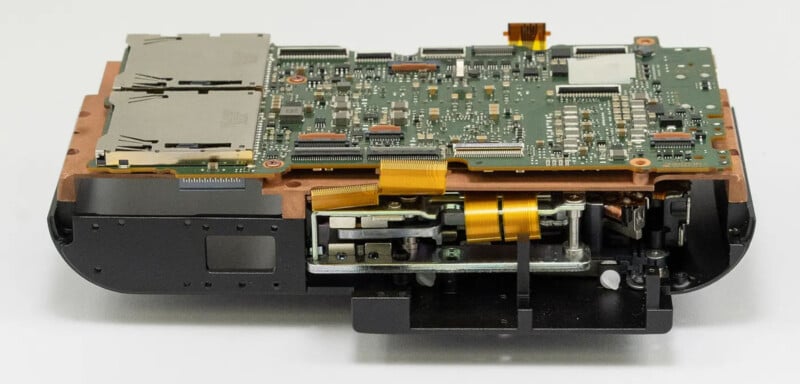

“I just assumed I will find a way to make it smaller. And I was in luck,” the photographer says. The G9 II has a decent amount of empty space inside, which would make the transformation much easier.

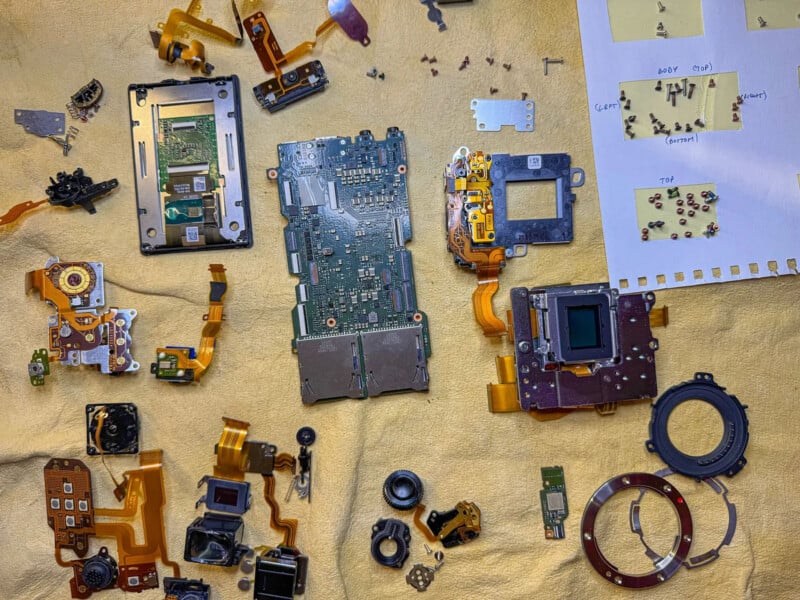

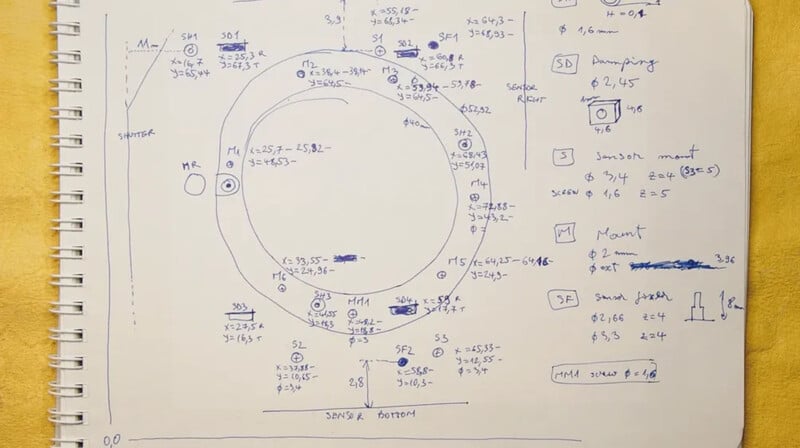

With the G9 II fully disassembled and all its critical components measured, it was time to start the design and planning process.

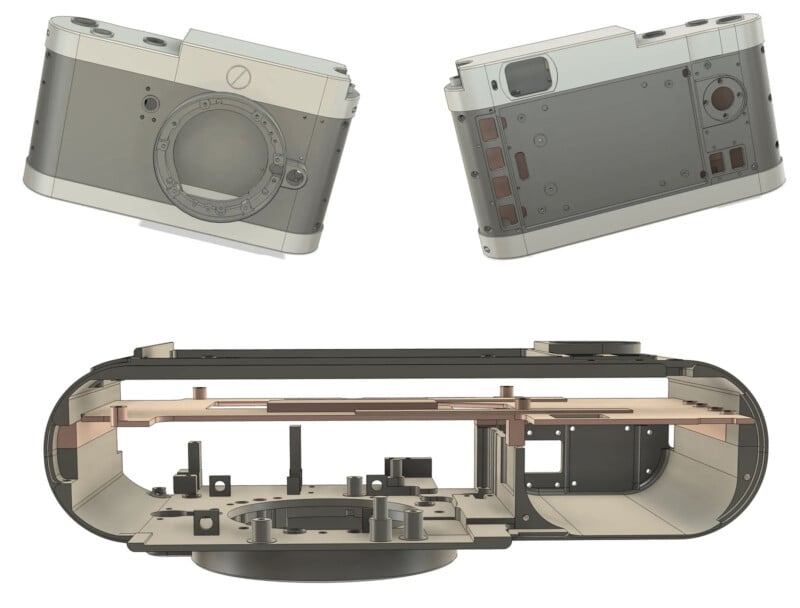

“The design program of choice was Fusion360. I had 0 experience with 3D softwares like this and my strategy was ‘do first, ask questions later.’ I changed multiple strategies as I was learning but ended up with one file and multiple components, one per part. Thinking like a programmer with multiple files and parameters was not flexible at all, like it is in programming,” Băluță explains.

This strategy ultimately worked, and the photographer soon had files and test 3D prints to help him further refine his design. The refinement process took months, and then he ordered proper, high-quality parts.

But the work was far from done; everything needed to fit together, which was not easy, and he needed to redesign the electronics to fit inside the new camera body, which was challenging as well.

But Băluță persevered, and ultimately, the project came together and looks exceptional, albeit imperfect.

“The biggest problem I have are the dials, they are quite loose and only one of them actually works, the shooting modes dial. The axles of this dials are very short and wide, they can be improved by making them longer, like one of them already is and works very well. Another problem is that the sensor is not calibrated correctly, it stays on springs. I did many measurements before disassembly but I couldn’t find the numbers anywhere in my notes. There is no visible problem in the final photos though,” the enterprising photographer remarks.

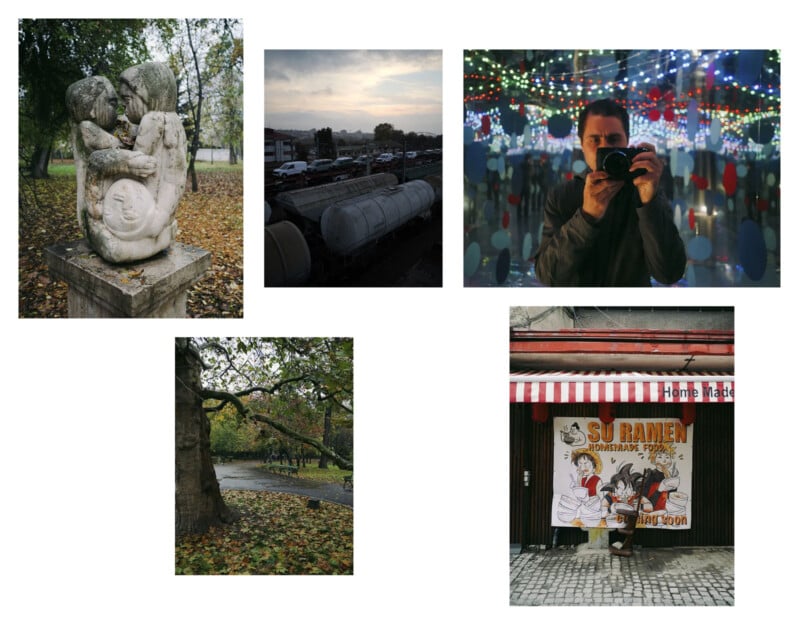

As the sample photos show, Băluță is correct; the final images look great despite minor issues with the sensor assembly. He also notes that the camera body gets warmer than he expected, and that, due to its entirely aluminum body, the camera’s Wi-Fi doesn’t work too well. He could have overcome this issue by using plastic parts, but he didn’t want to go that route.

When it is all said and done, the G9 II, a new battery, specialized tools, necessary components, custom CNC machining, PCBs, and 3D printing all add up to a bit under $2,700, which is significantly less than the cost of a brand-new Leica M camera.

Băluță’s “Leica G9 II” (left in each side-by-side) versus the Panasonic Lumix G9 II (right)

Băluță’s “Leica G9 II” (left in each side-by-side) versus the Panasonic Lumix G9 II (right)

“I still don’t have the camera I imagined, but I now know what it takes to build it. This build gave me proof that good hardware can be smaller and beautiful,” Băluță concludes. It’s not quite the perfect camera, and it’s not exactly how he imagined it, but Băluță says he plans to spend some more money on the project to resolve some of the issues and take it on his next photography trip.

While the photographer is quite hard on himself, there is no debating that he achieved something very impressive with the project. It is far from simple to take a camera apart and put it together in a different, thinner custom body. As for achieving the Leica look? We think Băluță nailed it.

Image credits: Cristian Băluță