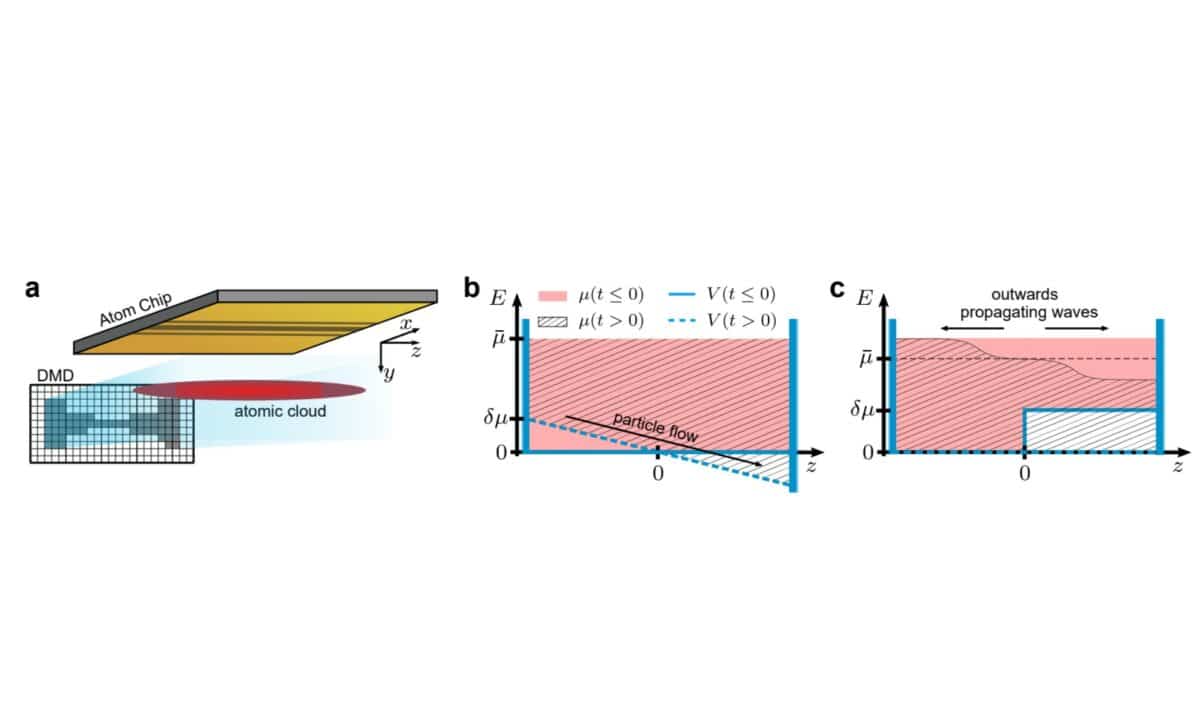

Researchers at TU Wien have made a breakthrough by creating a quantum system that allows energy and momentum to flow without resistance. By trapping thousands of rubidium atoms in a one-dimensional line, they observed an unprecedented form of transport where atomic collisions do not degrade the flow, offering a rare glimpse into a perfect conductor.

This new discovery challenges everything we know about the behavior of matter at the quantum level. In traditional materials like metals, heat and energy are dissipated due to collisions, but in this carefully controlled system, the atoms pass momentum through their collisions like a Newton’s cradle, without any loss. The findings, published in Science, open doors to a deeper understanding of quantum physics and the potential for resistance-free materials.

A New Look at Transport Phenomena

Transport is a concept scientists have studied for centuries, but it typically involves some form of resistance. For example, when heat moves through metal or charge flows through a wire, collisions between particles slow down the movement, dissipating energy. However, the researchers at TU Wien have now demonstrated that under very specific conditions, energy and mass can move through a quantum gas without any dissipation. By confining the atoms to a single line, the system behaved like a perfect conductor, in stark contrast to the typical diffusive transport seen in everyday materials.

Frederik Møller, one of the researchers at TU Wien, explained that in this experiment, the atomic system did not follow the usual patterns of either ballistic or diffusive transport. Instead, the motion remained sharply defined and undiminished, showing that the gas acted as a perfect conductor. This opens up new avenues for studying how resistance emerges or disappears at the quantum level.

Ballistic vs. Diffusive Transport

There are two fundamental types of transport: ballistic and diffusive. Ballistic transport occurs when particles move in a straight line without scattering, covering double the distance in double the time, much like a bullet traveling through space. Diffusive transport, on the other hand, is seen in processes like heat conduction, where energy is gradually shared between particles due to random collisions.

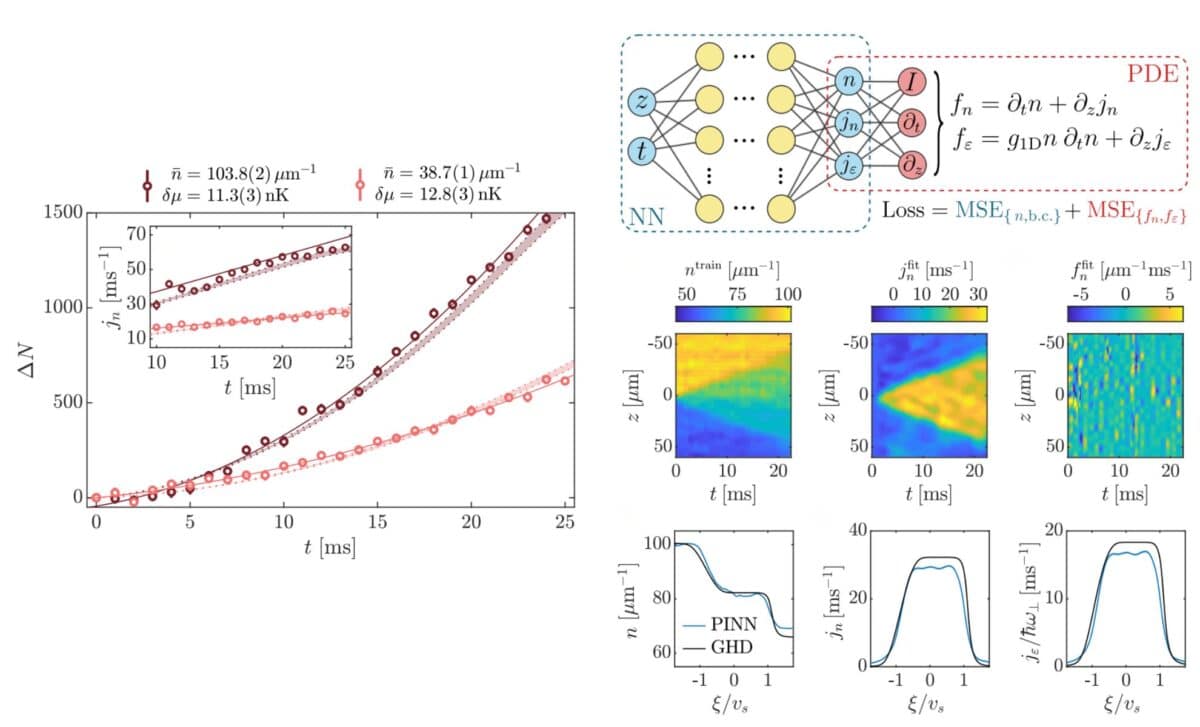

In this experiment, the rubidium atoms were confined to a one-dimensional quantum gas, and instead of diffusing, the energy and momentum stayed sharply focused, even after countless collisions. Møller noted that diffusion was “practically completely suppressed” in this setup. The behavior of the gas can be compared to a Newton’s cradle, where each atomic collision passes momentum to the next, without loss or scattering. This represents a new and unique form of transport that does not follow the normal rules of thermodynamics.

The Drude Weight and Quantum Transport

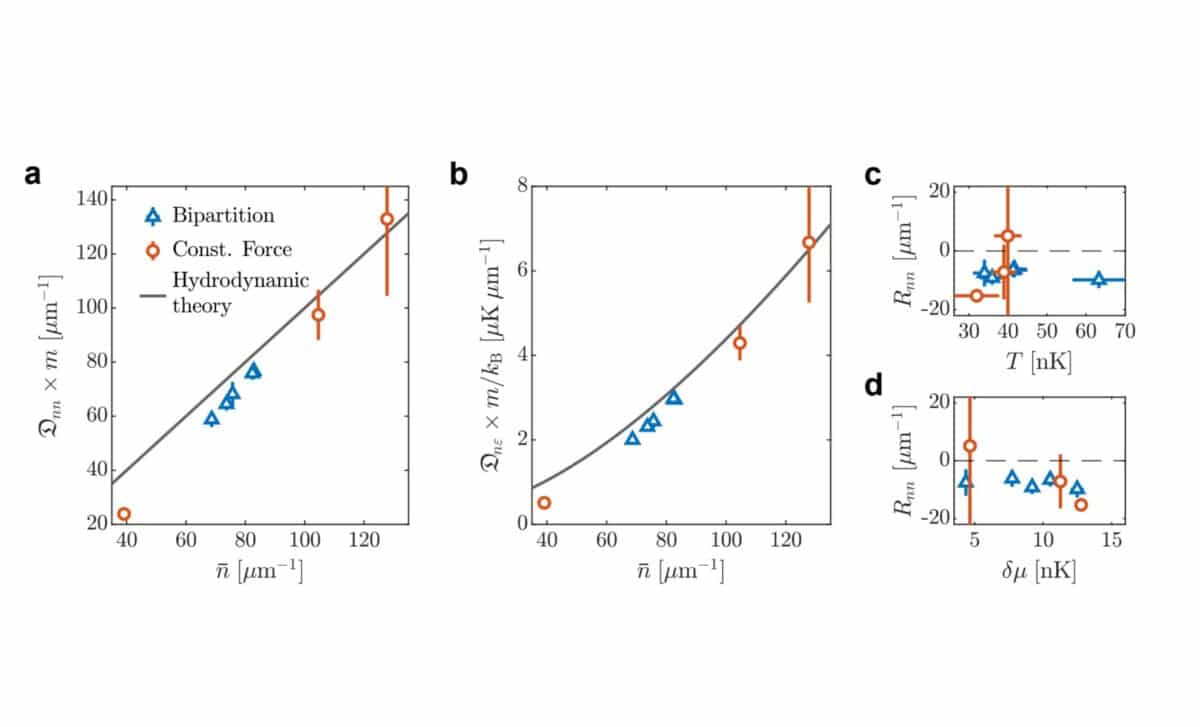

To understand this phenomenon more deeply, the researchers also measured the Drude weights of the system, a parameter that quantifies the ballistic transport of charge carriers. In traditional materials, Drude weights can be used to determine whether a material is a conductor or insulator. In the case of this quantum gas, the measurements showed that even at finite temperatures, the gas displayed nearly perfect, dissipation-free transport.

The team used two experimental protocols to induce currents in the gas: applying a constant external force and connecting two subsystems with different equilibrium states. Through these experiments, they were able to extract the Drude weights, which confirmed that the flow of mass and energy in the system was largely ballistic, even at higher temperatures. These findings further support the idea that the observed transport in this system is an almost perfect, resistance-free process, distinct from what is typically observed in everyday materials.

The experiments at TU Wien not only shed light on how quantum systems behave in unique, controlled conditions but also pave the way for future research into materials with no resistance, possibly revolutionizing fields like energy transport and quantum computing.