In 1940s Nazi-occupied Denmark, landscape architect Carl Theodor Sørensen noticed something: children ignored the playgrounds he built—they’d much rather make their own.

And so Sørensen came up with skrammellegepladser—junk playgrounds—the first of which opened in 1943 in Emdrup, on the outskirts of Copenhagen. It was a bombsite, but that was the point. Given hammers and free rein, children could use whatever they found—wood, ropes, tires, sticks—to dig, construct and build their own play spaces.

Old train engines, disused lifeboats, abandoned buses and unwanted railway carriages became arenas for imagination. Emdrup marked the start of a radical approach to childhood – more than just fun, it was empowerment.

Reporting on the stories that matter to you. Only with your support.

In 1946, British landscape designer and activist Lady Marjory Allen visited Emdrup and was inspired, championing the idea in the UK. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, she led the creation of over 35 adventure playgrounds.

At the heart of adventure playgrounds was ‘controlled risk.’ Children were encouraged to test their limits—climbing trees and structures, racing down hills, experimenting with tools and engaging in rough-and-tumble play.

Adventure playgrounds gave rise to the playwork movement—a profession that helps children play freely and take safe risks. As play expert Tony Chilton put it: “A grown-up who can help, but won’t boss, and the rest is up to children.”

Modern playgrounds by contrast, are clean, colorful and easy to supervise. What is left of that radical approach to making risk part of play? This question led me to visit Bristol’s four adventure playgrounds—Felix Road, The Ranch, The Vench, and St Agnes.

This story follows my journey through them, uncovering their histories and challenges, and meeting the passionate people creating these spaces where children are trusted, empowered, and free to play.

The Vench – Lockleaze Adventure Playground

In late August, senior youth and play worker Diana Sabogal invited me to a rare event: Bristol’s Adventure Playgrounds were coming together for a football tournament. Laughter carried across the street as parents chatted and toddlers darted between climbing frames.

“I first walked in randomly with my children,” says Dee, who has worked at The Vench for four summers. “Since then, it feels like we haven’t gone back home. My kids call it their second home.”

Sophia, 17, who grew up here and now works as a youth and play worker, adds: “It’s a safe space where kids can explore, make mistakes and grow. Today everyone’s having lunch, meeting new people—it’s a great way to connect with other adventure playgrounds.”

The Vench celebrated a multi-adventure playground football match. For those who didn’t want to play football, there were other things to do. Credit: Begonya Miranda.

The Vench celebrated a multi-adventure playground football match. For those who didn’t want to play football, there were other things to do. Credit: Begonya Miranda.

“Without play, I don’t think you can even exist,” says Augusta, a mother whose teenage daughters volunteer. “They learn teamwork, emotions and resilience. Through play, they actually learn life.” Ten-year-old Logan sums it up: “Responsibility. You take responsibility for yourself. It feels good to be trusted.”

The playground is also a place to build confidence. “In school, you’re shut in,” says 19-year-old Aster, a youth worker. “Here, you meet new faces all the time—you learn to get along, adapt and be part of something bigger.” Parents notice the difference: one mother explains how attending two days a week, as part of alternative learning provision, has boosted her son’s confidence and mental health. “He feels wanted again. Everyone’s so warm and welcoming.”

Families travel from Southmead, Easton and beyond. “It brings the postcodes together,” says Salah Hassan, playworker at Felix Road Adventure Playground.

It’s a safe space where kids can explore, make mistakes and grow.

Sophia, 17

Sophia highlights the playground’s wider impact: “Some kids come with a bit of a reputation. After a summer or two, you see them change. They learn to deal with things better. They start to trust adults again. This place keeps them out of trouble—and gives them a future.”

The Vench runs weekly sessions for primary and secondary-aged children, offers specialised activities like parkour workshops, and liaises with schools for one-to-one support. To sustain the model, they hire the space to other organisations—but staff capacity is stretched.

Behind the laughter lies a harder truth: The Vench is self-funded, reliant on volunteers and limited grants. “It should definitely be funded by the council,” says Brooke, a local mum. “Places like this keep children safe, give them independence and keep them off the streets.”

Rain begins to fall, but the footballers keep playing, shouting encouragement across the muddy field, undeterred.

Felix Road Adventure Playground

Adventure playgrounds are a world of their own. “Like time travelling to the ’70s,” says Tom Williams, manager of Felix Road Adventure Playground and Founder of Woodland Tribe. Splashes of colour and fearless children at play make it feel like stepping into Peter Pan’s Neverland. For 50 years, Felix Road has also provided free hot meals six days a week.

Tom, a lifelong advocate, holds a PhD on adventure playgrounds.traces his journey back to the 1980s, inspired by the freedom he saw during a trip to Denmark and Germany.

“These spaces,” he says, build not just memories but the “children’s emotional framework,” fostering independence, negotiation, resilience and community connections.

Ten-year-old Ramu, who for years had watched the playground from her tower block flat, recalls her first visit: “I thought it was gonna be for money until I came here and it was free. You just explore and have fun… Every culture is allowed here, and every race is allowed here. That’s what I really enjoy.” Now she comes most weekdays for crafts, water slides, and trips.

Felix Road Adventure Playground during Halloween celebrations. Credit: Begonya Miranda.

Felix Road Adventure Playground during Halloween celebrations. Credit: Begonya Miranda.

Felix Road faces challenges shared by many adventure playgrounds: rising insurance costs, occasional racial tensions, and strict regulations. “We are going to put a ‘No Drama Llama’ sign at the entrance,” says a playworker, inviting children to leave their issues outside.

For older children, the playground is a sanctuary. Casey, 14, loves the independence: “Adults are calm, nice, not shouty. You learn to share, explain things and make friends. If there’s a problem, adults like Wavy help you. But mostly, you handle it yourself. And if you fall, you get back up and play again.”

The playground’s strength lies in the autonomy it offers. “Parents say it’s like magic. ‘I’d never seen my child so focused.’ I say, it’s not magic, it’s freedom,” says Tom Williams.

Senior playworker Shaniem Biggs (aka Wavy) grew up at Felix Road. “Football was everything for me. Adventure, campfires, roasting potatoes, telling stories… anything you couldn’t do at home, you could do here. Safely, but with real freedom. Parents trusted the staff because they looked like you.” Wavy adds, “Regulations are stricter now, but the spirit remains.”

Felix Road’s ‘Drama Llama’ invites people to leave dramas outside the front gates. Credit: Begonya Miranda.

Felix Road’s ‘Drama Llama’ invites people to leave dramas outside the front gates. Credit: Begonya Miranda.

Adventure Play Manager Ollie Fournier says, “These experiences are crucial for helping kids develop confidence, resilience, and the ability to risk-assess. You’re in a relatively safe space to take risks and push yourself one step further.” Academics and frontline playworkers agree: risk-taking is intrinsic to growing up. Without it, young people seek risk elsewhere, and antisocial behaviour often follows because they lack spaces to be themselves.

Across generations—from children watching from flats to teenagers chasing footballs and crafting friendships—Felix Road Adventure Playground stands as a testament to the enduring power of play, freedom, and community.

The Ranch – Southmead

On a Wednesday afternoon in Southmead, the Ranch is buzzing. Kids drift between the music studio and the football pitch, make their own toasties, or simply hang out. Playworkers move among them with watchful eyes and ready smiles.

“This is a safe space,” says manager Delroy Hibbert. “Some kids just want to chill. Others want to learn music or sports. All of that’s fine.” His philosophy of respect and choice has guided the Ranch since he became manager two years ago.

When he arrived, the space was being used mostly by older teens. “I changed that. Parents didn’t want younger kids around older ones. Now it’s all secondary school age, years seven to eleven,” Delroy says “We still do some career-focused work with post-16s, but the main focus is youth services.”

The Ranch, Southmead. Delroy Hibbert (left) helps create a safe space for young people. Credit: Begonya Miranda.

The Ranch, Southmead. Delroy Hibbert (left) helps create a safe space for young people. Credit: Begonya Miranda.

Jack and Jesse, who began as attendees themselves, now mentor younger children. Jack DJs, Jesse produces music, and together they guide others in exploring creativity beyond what schools can offer. “At school, it’s stricter, more directed,” Jesse explains. “Here, you learn at your own pace.”

Amy, chief executive of Southmead Development Trust, coordinates programming across the Ranch and the nearby Greenway Community Space. “The Ranch and Greenway support each other. Kids move between music, sports, and other activities. It gives them a sense of community.”

If you fall, you get back up and play again.

The Trust traces its origins to the late 1990s, when locals transformed a former boys’ school into a community centre, later taking on the Ranch to create complementary spaces. “Post-Covid, we really focused on young people—they’re where we could have the most impact. It just seemed like a no-brainer,” Amy says.

The impact is clear. “It brings all the youth together. I meet people from different schools and do things I can’t do at home,” says a teen. Jesse adds, “It’s inclusive. The community is strong-knit. I don’t think there’s a single kid in Southmead who doesn’t come to the Ranch at least once a week.”

The Ranch is honest about life’s challenges. Teens joke about drama and disagreements, often sparked by events outside the playground. “Sometimes there’s beef,” one admits. “Staff help sort it out, and sometimes involve parents if it gets serious.” Amy acknowledges the heavy responsibility: “Safeguarding concerns are often passed to us to manage,” referring to how other institutions reach out to them for support.

Beyond play, the Ranch teaches life skills. Madison, a regular attendee, reflects, “You learn proper skills here.” Another girl adds, “This place is special. It’s got something in everyone’s heart.” For the children of Southmead, the Ranch is more than a youth club—it’s a second home, a launchpad for creativity, and a cornerstone of the community. And thanks to the partnership with Greenway, its reach stretches further.

St Agnes Adventure Playground

The African Caribbean heart of Bristol, St Pauls, has more community spaces than many areas—Docklands, St Pauls Learning Centre, Malcolm X Centre—but few dedicated solely to young people.

St Pauls Adventure Playground has been through dramatic ups and downs in recent years. In 2020, an arson attack destroyed the site — but its rebuilding became an unexpectedly transformative moment. A valiant community fundraiser brought it back to life, complete with an iconic tower where children could play piano while overlooking the M32.

But in the years that followed, like many council-owned spaces transferred to community management, it struggled with mixed funding streams and shifting leadership. In December 2023, it was suddenly forced to close. During the prolonged shutdown, a lack of maintenance led to significant deterioration. The much-loved tower had to be removed, and repair costs drained already limited funds.

Once again, the community rallied. The local church raised around £10,000, and Black South West Network stepped in to help strengthen management and long-term sustainability.

Finally, last April, the playground reopened with a new name—St Agnes Adventure Playground—and charity status.

Operational costs remain high. “It takes an astronomical amount of money to keep this building running,” says Sharon Benjamin, who has been involved in various capacities and now manages the playground. Yet she beams with excitement over a new heater and plans for floodlights.

The reopening brought Friday and Saturday sessions supported by Bristol City Council, alongside full-time holiday activities funded by the Holiday Action Fund. Sessions are run in partnership with 91 Ways, a group that uses food and language to bring people together. “We can’t run, we have to walk,” Sharon reflects. “Children need a safe space where they can talk to adults and eat for free.”

Staff and trustees involve young people in shaping the space. “After consulting with them, essentially the young people want a multipurpose sports ground,” explains Leigh McKenna, youth worker, community member, and new trustee. “Delivering on their ideas shows they are valued members of society and that their opinions matter. These spaces bring different young people together outside school. It’s a historic institution, very important to the community.”

Other residents are stepping in as well, including Dr Michele Curtis, artist of the iconic Seven Saints of St Paul’s murals and new trustee. “We redesigned the logo with staff, children, and residents,” she says. “It’s about community, learning through play, and teamwork.” One retiree volunteering at a fundraiser explains simply, “I just want to give something back.”

Despite ongoing challenges—insurance, maintenance, staffing—optimism runs high. St Agnes Adventure Playground has reinvented itself, surviving the storm and standing once again as a resilient beacon for young people in the community.

Fair Play

Adventure playgrounds are oases of freedom in a world built for convenience. Kids, like the rest of us, are drawn to the easy route—social media, endless scrolling, distraction. Traditional playgrounds entertain briefly—round and round the merry-go-round, up and down the see-saw—then boredom sets in.

Evidence shows children thrive when they have a real say in decisions affecting them, feeling empowered when their opinions shape the spaces they inhabit. Yet rigid school timetables leave little room for play, creativity, or risk.

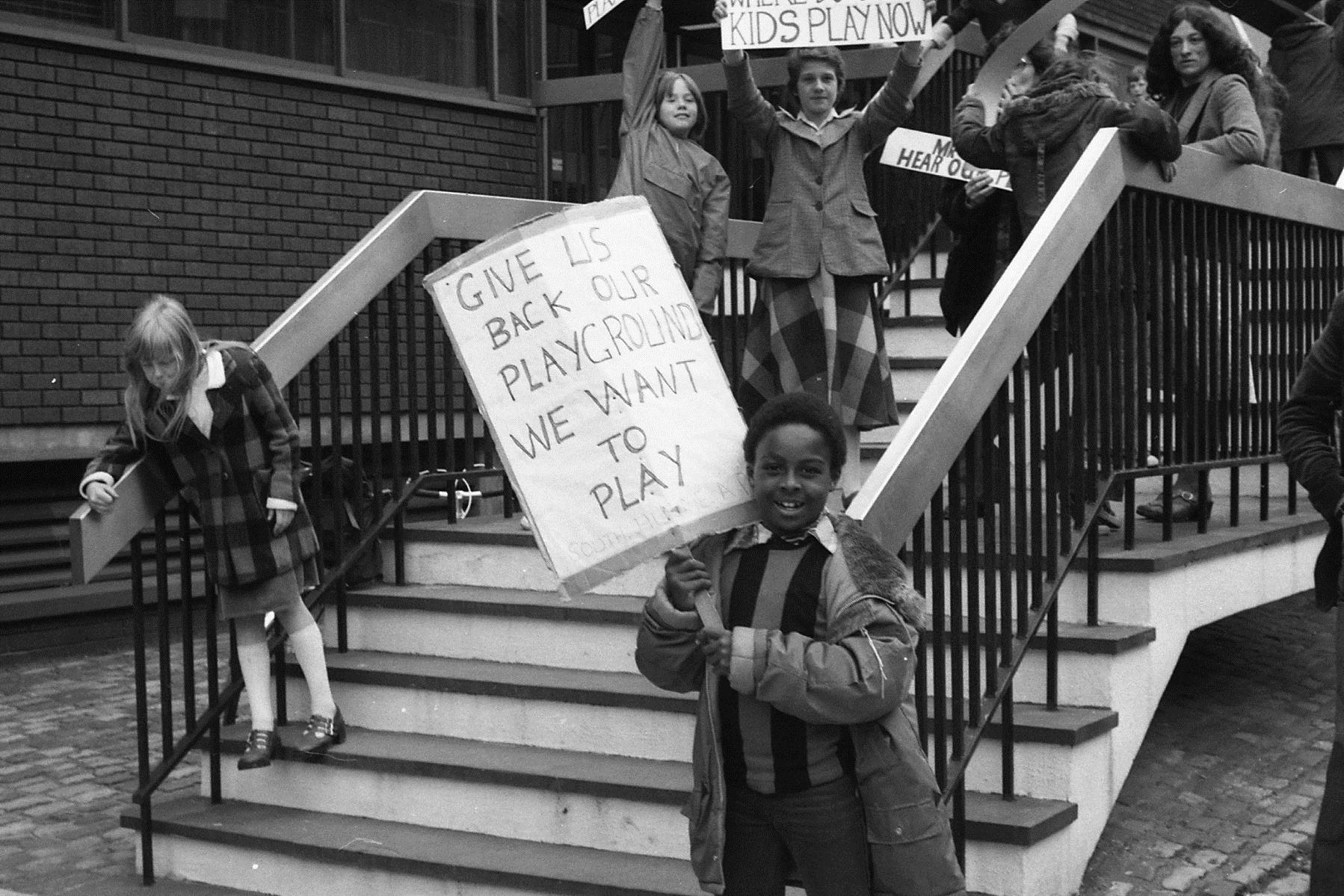

Children protest to keep their adventure playground open in 1980s Manchester

Children protest to keep their adventure playground open in 1980s Manchester

Adventure playgrounds are exhilarating—death slides, soaring zip lines, daring jumps—but the thrill is purposeful. Children learn to assess risk and discover their limits. Ironically, accident rates are lower than in conventional parks, proving that removing risk doesn’t make play safer, only diminishes opportunity for growth.

They are one of the vital “stops” along the school-to-prison pipeline—places where young people can veer off the path of exclusion and find freedom, creativity, and care. I think this pipeline can be interrupted by spaces that meet the needs the schooling system increasingly fails to recognise.

And yet, despite the vital role they play, adventure playgrounds operate under constant strain. Most exist on peppercorn rents, councils acknowledging their value but not covering maintenance, leaving the sites to shoulder those responsibilities alone.

Relationships with funders and authorities are appreciated, but often fraught, requiring constant negotiation and compromise. Playgrounds must bend to shifting managerial requirements, chase scarce funding pots, and navigate complex legal statuses just to stay afloat. On top of all this, in an increasingly over-sanitised society, even securing insurance has become an uphill battle.

Still, in the midst of all this precarity, adventure playgrounds persist, committed to the young people they serve. Living proof that, with even minimal support, communities can create their own forms of rescue—and that liberation, creativity, and resilience can all begin with a bit of risky play.

Independent. Investigative. Indispensable.

Investigative journalism strengthens democracy – it’s a necessity, not a luxury.

The Cable is Bristol’s independent, investigative newsroom. Owned and steered by more than 2,600 members, we produce award-winning journalism that digs deep into what’s happening in Bristol.

We are on a mission to become sustainable, and to do that we need more members. Will you help us get there?