Visitors to Christopher Hill’s Sussex retreat sometimes expressed surprise, tempered with concern, when they saw the crumpled order for his imprisonment, framed on the wall. In the mid-1960s, he had been sent to prison in Salisbury, now Harare, alongside six colleagues, at the behest of the government of Ian Smith. After a week of incarceration, Hill and his colleagues, having been sustained by a Fortnum and Mason hamper specially flown in, were put on a plane and deported from the country. Publicity from the event was not entirely unwelcome, in Hill’s case, leading to his appointment as a lecturer at York University.

Hill’s imprisonment had come about after his working for a year at University College, Rhodesia. He was opposed to government policy and aware of possible dangers, especially after he and some colleagues had sheltered a trade unionist, Josiah Maluleke, from arrest. Many people were involved in this subterfuge, Hill even taking the fugitive for a weekend at Lord and Lady Acton’s House, Mount Jalumba. Maluleke was never caught and eventually fled the country dressed as a woman and carrying a baby. As Hill wryly remarked in his memoir Looking In, “The baby’s fate is not known”.

In the years before Rhodesia, Hill, after graduation and a short period working in the City, had taken the Foreign Office exam. This was followed by a meeting for which he had turned up in top hat and tails, in his own words, “slightly tight”, having come straight from the Epsom Derby. All went well, and he found that he had joined the Special Intelligence Service, known in Whitehall as “The Friends”. MI6 was a perfect placement for Hill, with his excellent command of languages and easy sociable style. He described his time in the organisation as the best years of his life.

In SIS, he got to know “C”, Sir Maurice Oldfield, who was in charge, and many of the senior figures associated with the intelligence services. He was aided by his personable and highly articulate manner as well as his membership of various London clubs (his father, after Hill’s election, having paid for life membership of The Travellers). After time spent in the SIS office, where shoes were cleaned for the staff and morning tea brought, he was posted to Germany, quickly getting to know a wide range of notables, including figures from both sides of the Second World War, as well as members of the jeunesse dorée.

Elected to the exclusive Adelskub, otherwise reserved for members of the German nobility, he was asked to witness a duel, from which he sensibly excused himself. Looking for a change of career, he was sent to Bonn to see David Cornwell, first secretary at the embassy, who, as the author John Le Carré, later gained fame for his spy stories. Cornwell’s efforts to dissuade Hill included a convivial evening, which, having missed the last train to Frankfurt, resulted in his having to stay the night at the author’s house, his wife being somewhat displeased to discover a complete stranger in the spare bed (Cornwell having neglected to tell her about the unexpected guest).

After Hill’s return from Rhodesia, he became established in the politics department at York, where he was the founding director of the Centre for South African Studies, in its time a successful and highly regarded study centre for African politics.

Meanwhile, Hill’s lifetime interest in the Turf led to his purchase of a racehorse in 1971 and eventually to research and publication in 1988 of Horse Power. The title was reminiscent of a Dick Francis thriller, but the book was a serious academic study of the politics of the racing world. It was well-received, Hill’s laser-like attention to detail meaning that no stone had been left unturned in his quest for material. Subsequently, his work for the Jockey Club led to the graduate development programme, which he ran until his retirement in 1996.

Many of those who attended these residential courses went on to distinguished positions in and beyond racing. The success of Horse Power led to his book Olympic Politics (1992), a rather more onerous undertaking, Hill finding the labyrinthine machinations of Olympic officials and committees somewhat overwhelming. Eventually, he encountered the mysterious figure of Juan Antonio Samaranch Torelló, 1st Marquess of Samaranch, the Francoist president of the International Olympic Committee, who, after considerable prevarication, granted Hill a half-hour interview, which left him none the wiser.

Christopher Richard Hill was born in London and raised at Trotton Place, a Georgian manor house in Sussex. His father, Horace Rowland Hill, was a considerable figure in the City, having sold a prosperous family brewing business to become a stockbroker. After a first marriage, he married Hill’s mother in 1933. She had trained at the Royal College of Music but never pursued a musical career. At one stage, news of Horace Hill’s wealth had reached Maundy Gregory, Lloyd George’s purveyor of honours, and Hill senior was offered a baronetcy in return for £40,000, an offer which was promptly turned down.

The young Christopher was educated at Radley, which he enjoyed despite a polio-related physical disability which he had had from birth. He went up to Cambridge in 1953 to read moral sciences, and at Trinity College was taught by John Wisdom, himself a pupil of Ludwig Wittgenstein. The great philosopher’s influence was still paramount, teaching taking place in Wittgenstein’s old rooms, still furnished with the deck chairs provided by the frugal author of the Tractatus. Hill found, as did many others, aspects of Wittgenstein’s work to be impenetrable and years later, reviewing Bryan Magee’s biography of Wittgenstein for a BBC programme, described him light-heartedly, as “a cul de sac”.

Towards the end of his university career, Hill attempted school teaching, becoming, for a year or two, a visiting schoolmaster fellow at Cranleigh School. He enjoyed the experience and was popular with the staff, but claimed to have never quite grasped pupil discipline.

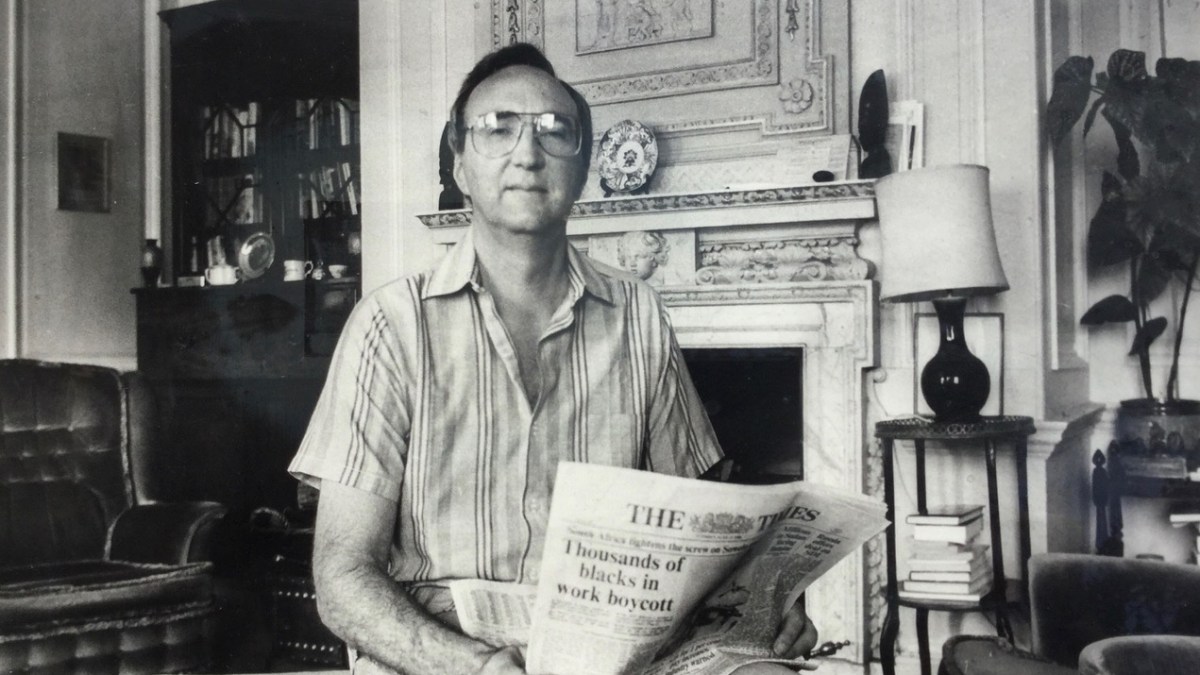

In retirement, he found plenty to do. His lifelong love of Africa led him to acquire a house in Cape Town, later building a superb coastal residence at Yzerfontein on the west coast of the Cape, where he spent several months of each year. This enabled him to keep up with friends and family, but he also continued writing, in particular obituaries of figures from domestic and African politics for The Times and the South African press.

Despite a lifelong interest in national politics, he never threw his hat in the ring, despairing of recent political trends. It is unfortunate that he never aspired to a high position in the intelligence services or the Foreign Office, to which his penetrating intellect and forensic insight could have led him. For the last 25 years of his life, he entertained friends, family and neighbours, aided by the Jeeves-like figure of David Musarurwa, a Zimbabwean by birth. He and his family became close friends.

Hill was widely read and took a mild interest in the arts but was never an enthusiast, adopting Talleyrand’s motto: “Surtout pas trop de zèle” — above all, not too much zeal.

Christopher Hill, racing expert, teacher and MI6 agent, was born on March 4, 1935. He died on November 1, 2025, aged 90