Getty Images

Getty Images

New taxes on expensive homes and private jet travel along with changes to income tax were among the proposals in the Scottish government’s latest budget.

Scotland’s finance secretary Shona Robison says the spending proposals help families and will aid efforts to eradicate child poverty.

But who are the budget’s winners and losers?

BBC Verify has examined what we know about how the Scottish budget is likely to affect different groups across the country.

The winners

The Scottish government described this as a cost of living budget, and the key measures were chiefly aimed at families.

The Scottish Child Payment – a flagship policy which provides a weekly payment to families who are in receipt of certain benefits such as universal credit – is to be expanded to £40 a week for children under the age of one.

The government has also pledged to set up breakfast clubs for every primary school and special school in the country.

Both of these policies are slated to begin in 2027, so are really a matter for next year’s budget – after May’s Holyrood election, and which could thus be viewed more as campaign pledges.

There is an extra £2.5m of funding in this draft budget for more afternoon and evening activities after school.

And there is cash for more sports provision, marking Scotland’s men’s World Cup qualification and Glasgow hosting the Commonwealth Games this summer – including a promise of free swimming lessons for every primary pupil.

Scotland’s further education colleges are also in line for a boost in funding, to the tune of £70m.

Audit Scotland analysis had suggested the sector suffered a 20% real-terms cut in funding, and the Scottish Funding Council warned last year that most colleges face unsustainable losses.

Finance Secretary Shona Robison said the extra cash – a 10% uplift on the 2025-26 budget – was an opportunity for the sector to demonstrate how it could help Scots fulfil their potential and meet the nation’s workforce needs.

Businesses had also been demanding extra support, with concerns about a looming revaluation of the non-domestic rates which are levied on premises.

As a result all three bands of business rates – the basic, intermediate and higher property rates – are being cut.

Other “transitional” reliefs are also being brought in to ease the move to the new system, including an extension of the “small business bonus” scheme which lifts smaller properties out of paying anything.

The Scottish Fiscal Commission had forecast that the new valuation of properties would increase revenues by £290m, but that changes announced in the budget would cut that by £153m.

Some business groups had been calling for the revaluation process to be put on hold, and Robison stopped short of this.

However she also said she would make further support available “if additional resources become available”, citing speculation about changes to tax plans in the rest of the UK – where businesses have also raised the alarm about the revaluation.

The losers

In terms of losers, the plan for a “mansion tax” in Scotland was one of the more eye-catching announcements in the budget.

A budget of £5m has been put aside for a “targeted revaluation” of certain properties, in a bid to create two new council tax bands targeting houses worth more than £1m in 2027.

Analysis by estate agent Savills in February 2025 suggested there were more than 11,000 houses in Scotland at that price range, and Public Finance Minister Ivan McKee told BBC Scotland it could raise £14m.

That money would go directly to local councils – and some may benefit more than others, based on where the highest value properties are.

However, there will not be a broader revaluation of Scotland’s properties – meaning the rest of the council tax system will remain based on house prices determined in 1991.

The Scottish government had estimated that a nationwide revaluation would see roughly half of Scotland’s homes change council tax band, and that kind of upheaval has long been seen as a barrier to reform of the levy.

This – along with plans for a tax on private jet flights earmarked for 2028 – continues the Scottish government’s approach of asking those who are better off to pay more towards public services.

And the changes to the devolved income tax system underline this.

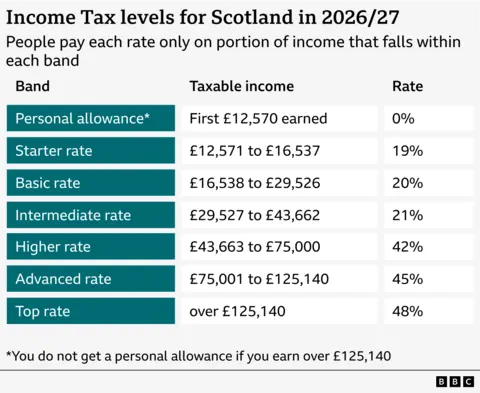

Scotland has its own income tax system, which has moved in a distinctive direction with six different bands ranging from 19% to 48%.

The Scottish government calls this a more progressive system, because it raises more from those with the broadest shoulders while charging average and lower earners a bit less.

Phil Sim outlines the main things we learned from the Budget

Phil Sim outlines the main things we learned from the Budget

The SNP has long pledged that a majority of Scots will pay less income tax than if they lived elsewhere in the UK.

Ministers have sought to achieve this by raising the thresholds where the lower rates kick in by 7.4% – double the rate of inflation – while freezing those for the higher rates.

Forecasts suggest that means 55% of taxpayers in Scotland will pay slightly less – although by a margin of at most £40 a year.

Meanwhile someone earning £50,000 will pay almost £1,500 more than if they lived in England – with ministers arguing this is in return for better-funded public services.

All of this is based on forecasts from the Scottish Fiscal Commission – and given forecasts are not always bang on, the reality can be a little more tricky.

Data on tax actually collected in 2023-24 showed that slightly more Scots had actually paid more tax than they would if they lived elsewhere in the UK.

Ministers have given themselves a bit more margin for error this year, and are confident their promise will be delivered based on the latest SFC estimates.

They will be hoping that the pledges included will be enough to deliver them back into government after voters go to the polls.

Phil Sim outlines the main things we learned from the Scotland Budget

Additional reporting by Aimee Stanton, Andrew Picken and Phil Leake