Stay informed with free updates

Simply sign up to the Artificial intelligence myFT Digest — delivered directly to your inbox.

Barclays has published a Special Report: ‘AI gets physical’. Here’s the opening pitch:

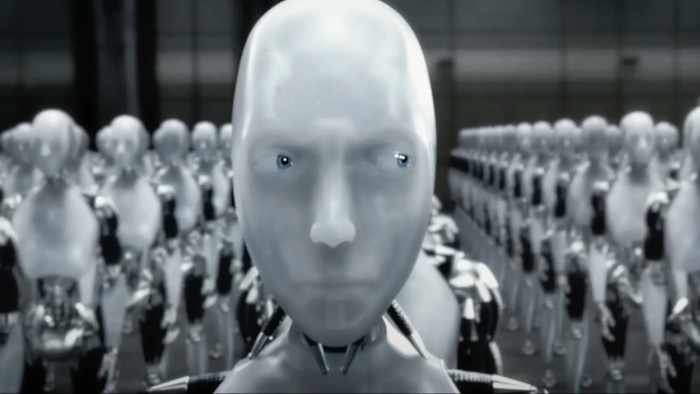

AI’s next frontier is physical: humanoid robots – robots in human form – are stepping out of the lab and into the real world. They could take on the tough, repetitive jobs humans increasingly avoid in manufacturing, agriculture and healthcare – working alongside people and augmenting the workforce.

Authors Zornitsa Todorova and Carlos Eduardo Garcia Martinez write that a 30x drop in unit costs over the past decade means that the market for these “humanoids” — which they describe somewhat imprecisely as “cars in miniature” — could grow from $2–3bn today into a (“most-optimistic” scenario) $200bn industry by 2035. The tailwinds include ageing populations, growing urbanisation and shifting job preferences.

Obviously, the calculations underpinning that figure …

Estimating the total addressable market (TAM) is challenging, and projecting its future even harder given the many moving parts. To address this, we aggregated a broad range of sources from AlphaSense – company reports, industry articles, white papers, earnings transcripts, and expert commentary – to build a forecast model across three scenarios: baseline, conservative, and optimistic.

… are very vague.

The big breakthrough (they reckon) is AI, which (they reckon) is good enough that (they reckon) these robots now (they reckon) understand context. They are significantly more optimistic than, say, MainFT’s Sarah O’Connor, who wrote about this same issue earlier this week.

You can read the report in full here. We just wanted to dwell on one part. The authors write:

[Humanoid robots’] advantage lies in near-continuous operation: even at half human efficiency, a humanoid can deliver 25% more output per day, and at parity, up to 150% more, according to our analysis.

They expand on this later on in a section called “Labour force augmentation and productivity”. The authors name some “roles with the greatest potential for humanoid robot adoption” (high-res):

It’s notable that a job being “emotionally demanding” is supposed to make it *more suitable* for a robot

It’s notable that a job being “emotionally demanding” is supposed to make it *more suitable* for a robot

And write (their emphasis):

While it is still uncertain whether humanoid robots can match human efficiency, their technical advantage lies in near-continuous operation. Unlike humans, a humanoid can run almost 24/7, with only short breaks for battery charging. For example, assume a human in a logistics facility delivers 8 productivity hours per day. A humanoid operating in 6-hour cycles (5 hours of work followed by 1 hour of recharge) allows for 20 work hours in a 24-hour period. If its efficiency is only half that of a human, that equates to 10 productivity hours per day, or 25% more output than a human. If the humanoid matches human efficiency, its output jumps to 20 productivity hours per day, or 150% more than a human worker.

First, the technical part of this: that six-hour cycle proposal is based on the trailed “peak performance” specs for Figure AI’s F-03 battery, designed for its Figure 03 humanoid, which very much does not yet exist as something a company can actually buy. Maybe it will exist someday, but this isn’t exactly a hype-free sector.

Now, the non-technical part. Here’s another quote:

The prolongation of the working day beyond the limits of the natural day, into the night, only acts as a palliative. It quenches only in a slight degree the vampire thirst for the living blood of labour. To appropriate labour during all the 24 hours of the day is, therefore, the inherent tendency of capitalist production. But as it is physically impossible to exploit the same individual labour-power constantly during the night as well as the day, to overcome this physical hindrance, an alternation becomes necessary between the workpeople whose powers are exhausted by day, and those who are used up by night. This alternation may be effected in various ways; e.g., it may be so arranged that part of the workers are one week employed on day-work, the next week on night-work.

That quote, in case it isn’t clear, is not from Barclays. It’s from Capital (Volume 1), written by a guy called Karl Marx and published in 1867.

We flag it because the existence of shift work doesn’t seem to have been factored into Barclays’ calculations. If a robot is half as efficient as a human per hour, it’s half as efficient as a human per hour. And if working 24 hours straight is too much for one of these fabulously efficient fleshbags, then 24-hour businesses will just… hire more.

And yes! Shift work has loads of horrible consequences, workers in logistics facilities are often exploited, and of course if there does reach a point where a continuously-working robot is cheaper than three humans (whether due to falling costs, labour shortages or anything else), we’re sure companies will jump right on it. Marx probably had some thoughts on that kind of thing too.

Update: Incidentally, if you want to consider the humanoid robot takeover in the context of Barclays’ other 2035 predictions, here’s their whole entire trends matrix, published on Monday (high-res):

You’ll find “humanoid robotics” just next to “diversity and inclusion”. Make of that what you will…