Two of Antarctica’s most fragile glaciers already sit at the heart of sea-level rise projections. But new evidence from the ocean floor suggests their vulnerability is not new.

When Earth was only a few degrees warmer than today, this same stretch of ice in West Antarctica repeatedly unraveled – retreating deep inland before rebuilding again, over and over.

The evidence comes from sediments drilled offshore in the Amundsen Sea, just beyond today’s rapidly thinning Thwaites and Pine Island glaciers.

Those muddy layers record how the edge of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet behaved during the Pliocene, a time when global temperatures and sea levels were higher than today.

The record tells an unsettling story. Each retreat released icebergs, reshaped the coastline, and likely drove major sea-level rise – offering a geological preview of how this region can respond when warming pushes it past key thresholds.

Antarctica’s most dangerous glaciers

Thwaites and Pine Island are already among the fastest-melting glaciers on the planet. Together they dominate ice loss in West Antarctica’s Amundsen Sea sector.

That’s why researchers are trying to understand what warmer conditions do to this part of the ice sheet, not just in models, but in real geological history.

To do that, scientists often look to the Pliocene, between about 5.3 and 2.58 million years ago.

Global temperatures were roughly 3 to 4 °C (about 5 to 7 °F) higher than today, and sea levels were more than 15 meters (nearly 50 feet) higher. A substantial share of that rise came from Antarctic ice.

Clues buried beneath the ice

The new work focused on marine sediments recovered during IODP Expedition 379, specifically from Site U1532 on the Amundsen Sea continental rise.

The basic idea is simple: as glaciers advance and retreat, they leave a signature in the mud offshore. Over millions of years, those layers stack up like pages in a book.

The team, led by Professor Keiji Horikawa from the University of Toyama, examined how those layers changed through time.

They were looking for evidence of warmer intervals when ocean waters opened up and ice margins destabilized, as well as colder intervals when ice expanded across the continental shelf.

“We wanted to investigate whether the WAIS fully disintegrated during the Pliocene, how often such events occurred, and what triggered them,” said Horikawa.

Sediments reveal climate shifts

In the cores, the researchers identified two repeating layer types that tracked alternating climate phases.

Thick, finely layered gray clays pointed to colder glacial periods, when ice spread widely across the shelf. In contrast, thinner greenish layers signaled warmer interglacial conditions.

That green tint mattered. It comes from microscopic algae, which implies open water and reduced sea ice. In other words, the ocean above these sediments was not locked under permanent ice during those intervals.

Even more telling, the warm-phase layers contained iceberg-rafted debris, or IRD. These are small rock fragments carried out to sea by icebergs that calved from the Antarctic margin. When the icebergs melted, they dropped the debris onto the seafloor.

Between 4.65 and 3.33 million years ago, the team identified 14 especially strong IRD-rich intervals. Each was interpreted as a major melt-and-retreat episode, when the ice margin pulled back and released a surge of icebergs into the Amundsen Sea.

Tracing Antarctica’s ice retreat inland

Seeing debris offshore is one thing. Knowing how far inland the ice pulled back is the harder part. To get at that, the researchers used geochemical “fingerprints” to trace the source regions of the debris.

They measured isotopes of strontium, neodymium, and lead. These isotopic ratios vary across West Antarctica depending on the age and type of bedrock.

By comparing the signatures in the debris with modern seafloor sediments and bedrock samples, they could identify where the material likely originated.

A key result is that much of the debris appears to match rocks from the continental interior, especially the Ellsworth–Whitmore Mountains.

That’s significant because those mountains sit well inland. If their material is ending up in iceberg debris offshore, it implies the ice margin had retreated far enough to excavate, transport, and calve ice containing that interior signal.

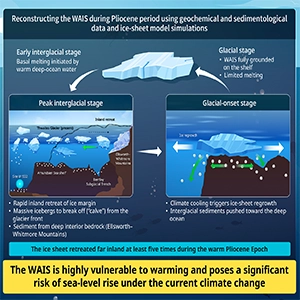

By studying Pliocene sediments deposited when Earth was warmer than today, the researchers found that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreated far inland at least five times. Credit: Professor Keiji Horikawa from the University of Toyama, Japan. Click image to enlarge.Glaciers collapsed but rebounded

By studying Pliocene sediments deposited when Earth was warmer than today, the researchers found that the West Antarctic Ice Sheet retreated far inland at least five times. Credit: Professor Keiji Horikawa from the University of Toyama, Japan. Click image to enlarge.Glaciers collapsed but rebounded

The sediment record also suggests a consistent rhythm to these Pliocene shifts. The team describes a four-stage pattern.

In cold glacial phases, the ice sheet was extensive and comparatively stable on the shelf. As climate warmed into an early interglacial stage, basal melting increased and the ice began to retreat inland.

At peak warmth, large icebergs calved from the shrinking margin and carried interior-derived debris across the Amundsen Sea, leaving those IRD-rich layers behind.

Then, as temperatures cooled again into a glacial-onset stage, the ice rapidly regrew, reworking and pushing sediments toward the shelf edge and farther downslope.

This is not a picture of a single, permanent collapse. It’s a picture of repeated, fast retreats followed by rebounds – events that could still drive major sea-level rise while they are happening.

“The Amundsen Sea sector of the WAIS persisted on the shelf throughout the Pliocene, punctuated by episodic but rapid retreat into the Byrd Subglacial Basin or farther inland, rather than undergoing permanent collapse,” said Horikawa.

Lessons for Antarctica’s future

The takeaway is sobering. The ice sheet in West Antarctica has a history of retreating far beyond its current position under temperatures that are not wildly outside what the planet could reach again. And it appears capable of doing so in bursts, not just slow, steady steps.

That matters because the Amundsen Sea sector is exactly where today’s biggest worries sit.

If Thwaites and Pine Island continue to thin and grounding lines continue to migrate, the system may be pushed toward thresholds that past climates have already crossed.

The Pliocene doesn’t offer a perfect blueprint for the coming century. The geography was similar, but ocean circulation, greenhouse gas trajectories, and the pace of change differ.

Still, the sediment story delivers a clear warning: this part of Antarctica can retreat rapidly when conditions allow, and it has done so repeatedly before.

The study was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–