Everyone is quick to look to space and the vast universe as the most important area to explore, but right here on Earth, much of our oceans lie completely untouched and undiscovered. Why travel all the way to space when we still have numerous revelations to make here? Chinese scientists are doing just that, by looking deep into our untouched oceans to find what is lurking beneath.

How much of our ocean have we actually explored?

Even though the ocean covers around 75% of our planet, we know surprisingly little about what lies beneath its surface. With scientists and researchers so focused on the universe outside our planet, we have been ignoring the multitude of biodiversity we have yet to find, a whole lot closer to home.

It is estimated that only 5% of all oceans and seas have been explored directly, through observation and submersibles. More has been mapped using advanced technology, but that still only makes up about 20-26% of the entire ocean environment.

Although it appears we have a lot of information about many marine animals and organisms, we are actually only aware of about 10-20% of all ocean life, and many of those species we only know a small amount about. Overall, about 70-90% of the ocean remains undiscovered. While many scientists are looking to the sky for the next age of discovery, Chinese explorers are dedicated to looking below, and are finding things we’ve never seen before!

Deep ocean trenches hold unexpected life, and the Chinese are out to learn about it

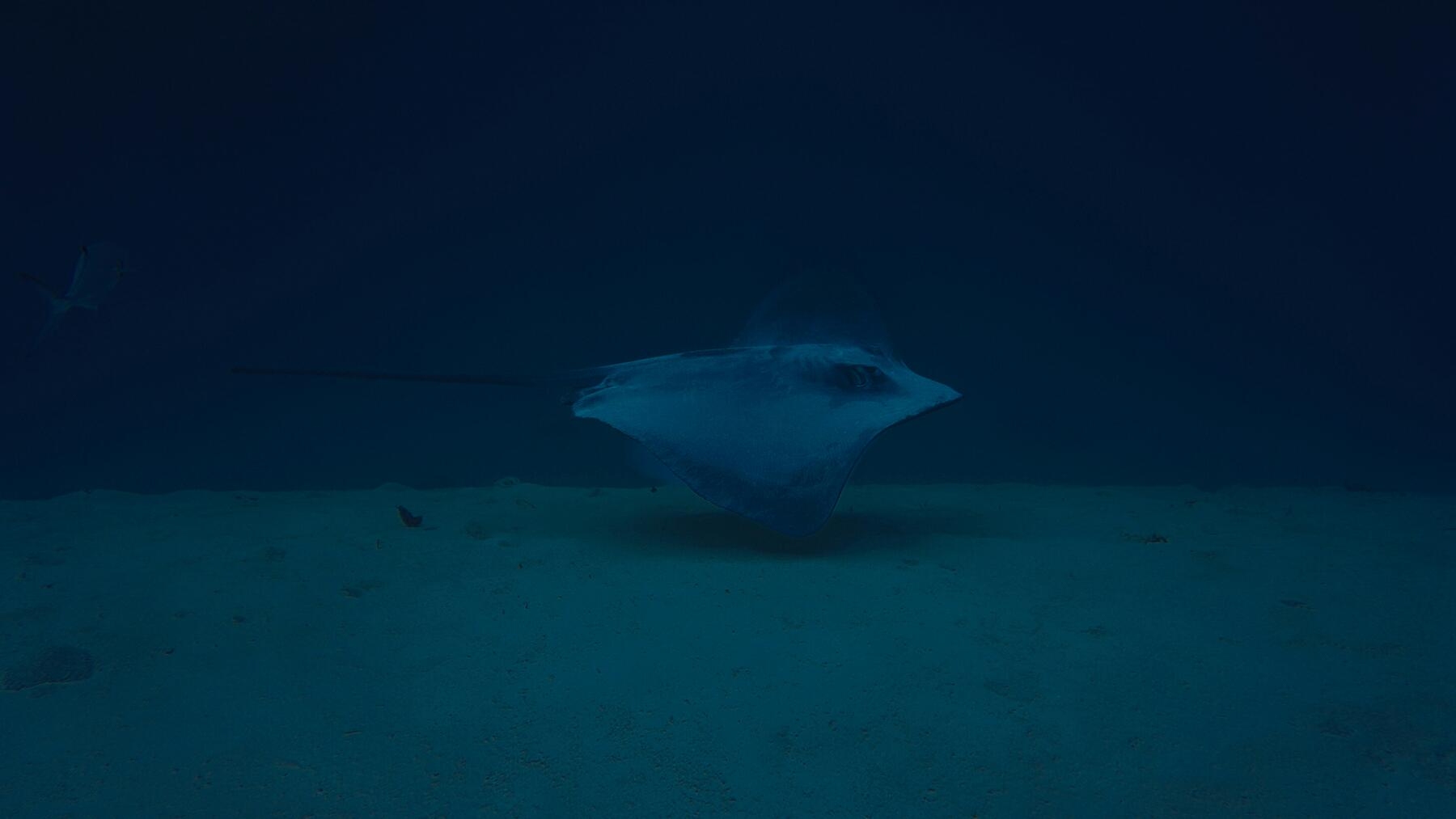

It used to be thought that not much goes on deep below the ocean due to a lack of light and warmth, but that idea has long been overturned. We know that many species can live far beneath the surface of the ocean, but just how far is the question.

The Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Deep Sea Science and Engineering has set off to discover just how deep organisms can be found, and the results are fascinating. This team has been exploring the Kuril–Kamchatka Trench and the western Aleutian Trench in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, going as deep as 9,533 meters (around 30,000 feet). According to Discover Wildlife at the BBC Wildlife Magazine:

“It was thought that life in the hadal zone (depths below 6,000 metres) was sparse, limited by intense pressure, near-freezing temperatures, and a lack of sunlight.”

While there have been other intriguing ocean discoveries of late, this Chinese team observed something even more interesting…where there were chemical seeps upon the ocean floor at such depths, communities of life were actually clustering around. What were these creatures doing at such depths, and why were they attracted to these chemicals? The answer lies in a process known as chemosynthesis, where microbes convert chemicals into energy.

Newly discovered chemosynthetic communities in the hadal zone

The human-occupied submersible Fendouzhe, which reached these depths, discovered species that had never been found before. Organisms such as tube worms, clams, and crustaceans were found, with the most popular organisms sighted being iboglinid Polychaeta (marine worms with no mouth or digestive system) and Bivalvia (a class of mollusks), presumably living off the chemosynthetic bacteria that form the basis of the food chain for these larger organisms. According to the researchers who made the discovery, these organisms were:

“Sustained by hydrogen sulfide-rich and methane-rich fluids that are transported along faults traversing deep sediment layers in trenches, where methane is produced microbially from deposited organic matter, as indicated by isotopic analysis.”

The documentation of life in these hadal trenches is extremely rare, so this Chinese expedition is quite astonishing. This discovery may have just found the most extensive chemosynthesis-based community ever, and, despite many scientists simply wanting to look to space, it indicates just how much we still can find within our own planet.

If you want to learn more about this discovery, you can consult the full study: Peng, X., Du, M., Gebruk, A. et al. Flourishing chemosynthetic life at the greatest depths of hadal trenches. Nature 645, 679–685 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-025-09317-z