There’s something magical about the idea of a business that makes satellites, fires them into space and controls them as they zoom around, cataloguing what is happening on Earth.

Rafel Jordá Siquier, the founder and chief executive of a British small satellite operator called Open Cosmos, has been doing just that since the age of 25, when he convinced his first customers to cough up the necessary cash. Since then his company has launched a dozen satellites ranging in size from a microwave to a large fridge on rockets operated by the likes of SpaceX and Arianespace.

The beauty of these small satellites is fleeting. Sitting in a low Earth orbit, between 400km and 2,000km from the surface of the planet — the “sweet spot” for satellites — and travelling at speeds of 7km a second, they traverse the planet every two hours and can hold their position for at least five years. But, inevitably, they begin to lose altitude, turning into plasma as they re-enter the atmosphere.

Rafel Jordá Siquier, the founder and chief executive of Open Cosmos

OPEN COSMOS

• Ministers back ‘rapid response’ satellite plan to end reliance on US

At the moment Open Cosmos, which is based at a science park in Harwell, Oxfordshire, has seven active satellites providing data and monitoring services to governments in Europe and to companies, as well as images of what is happening around the world, whether on Ukraine’s borders or supporting emergency relief in Valencia following the devastating floods in 2024.

The profitable, £29.7 million turnover business won new orders so quickly in the three years to December 2024 that it earned a place on this year’s Sunday Times 100 Tech ranking of Britain’s fastest-growing tech firms. Last year it landed even more, including one worth about £29 million to launch satellites for the European Space Agency.

However, this week its fortunes changed up a gear again. On Wednesday it revealed a coup. With the help of the UK government it has pipped much larger rivals to secure the rights to use a global high-priority radio spectrum for its space to Earth communications services.

It will mean it can roll out an even more resilient satellite system for the UK and Europe to meet their sovereign communication needs. “That is transformational — really, really big,” Jordá says.

Open Cosmos has acquired the licence, for an undisclosed sum, from the tiny principality of Liechtenstein, which had the wherewithal to move faster than any other country to apply for a new slice of radio spectrum with the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), which defines pockets of spectrum that are available.

This global “Ka-band” licence has priority over others, meaning that if another satellite provider, say Elon Musk’s Starlink, began to send interfering signals, the regulatory body would give priority to Open Cosmos.

The successful launch and orbit of Open Cosmos’s Mantis satellite last year was “a major milestone in agile Earth observation”, according to the UK Space Agency

OPEN COSMOS

The British company expects to start deploying satellites in a specific set of orbits using the Ka-band by April, launching the first from New Zealand. Jordá would not confirm the scale of the launch programme but hints at a large number: “It will definitely be one of the highest that has ever been seen in Europe.” Amazon Leo began launches last April and will have a constellation of 3,000 satellites. Starlink has more than 9,400 active satellites, with plans to reach 12,000. Both sell services to consumers directly — many more satellites are required to support mobile phone devices. Open Cosmos is focused on services for governments, researchers and companies, and so can make do with a smaller number.

Jordá says the Liechtenstein licence is “extremely valuable”. Last September Starlink acquired lower bandwidth spectrum rights over the US from EchoStar for $17 billion. While it has raised $64 million in venture capital and plans to raise more, Open Cosmos does not have that kind of war chest. “It is no secret that we cannot pay billions for an asset of this kind,” Jordá says.

“We can offer other things — our speed, our commitment, our technology — that have a lot of value. This is strategic for the UK and without the support from the highest levels in government it would have been very difficult for a company like Open Cosmos to be in this position. It is also strategic for other European countries… for systems of this nature to emerge from Europe in order to keep our competitive resilience.”

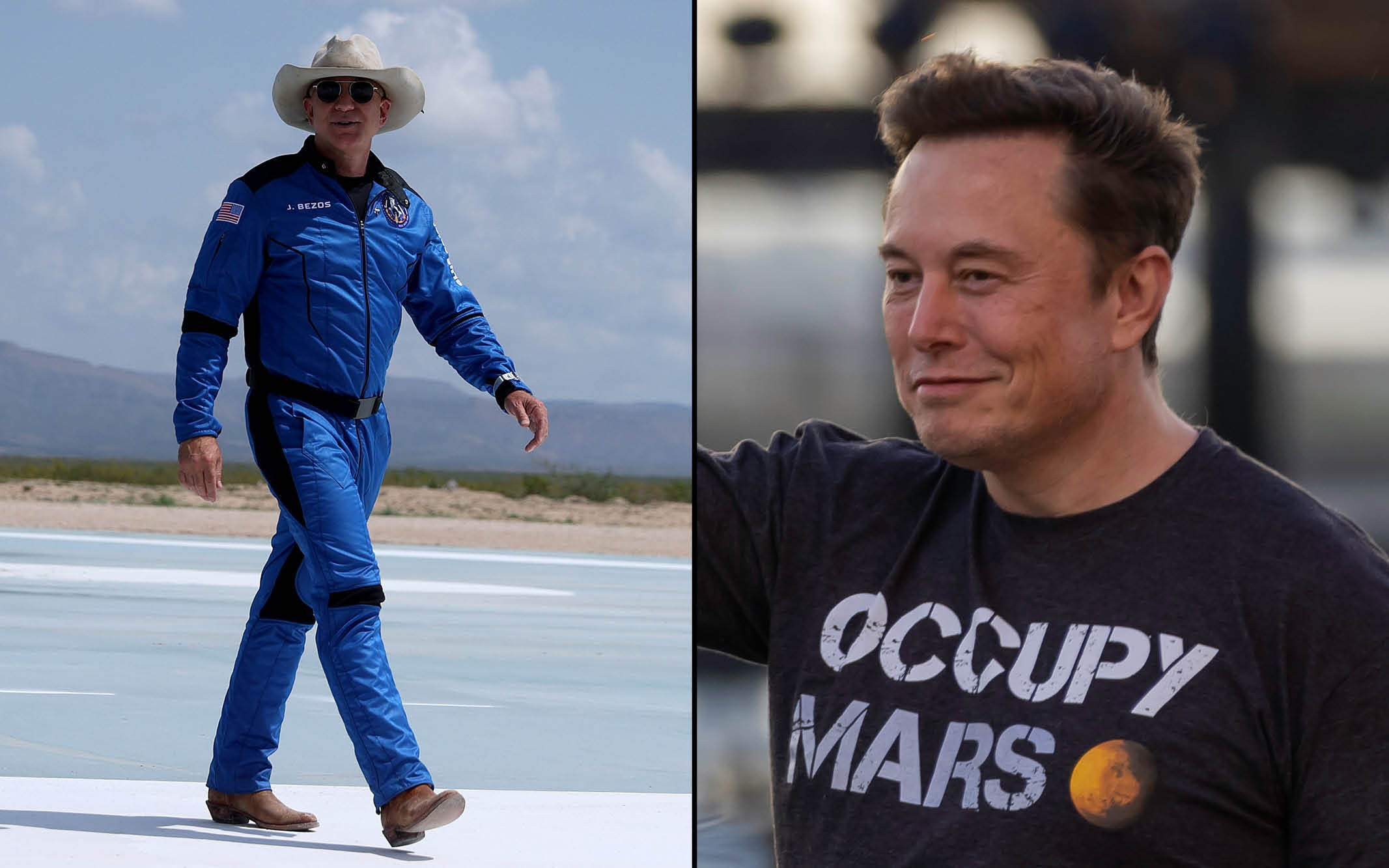

He’s clear that the creation of a new sovereign constellation of low Earth orbit communications satellites would be “an invaluable asset for the UK and Europe”, providing alternatives to the US systems owned by the billionaires Musk and Jeff Bezos.

“We will be able to build a satellite infrastructure that enables the UK and Europe not to have to depend on what Elon [Musk] wants to do, or what Jeff [Bezos] wants to do. It will play into a key strategic asset that the UK and Europe should leverage in order to be able to offer, from a position of strength, relationships and international collaborations.”

Jeff Bezos, left, and Elon Musk have made big investments in the space sector

• UK firms win £16m to provide secure satellite communications

Jordá set up Open Cosmos in 2015, aged 25, leaving his job at Airbus after seeing SpaceX successfully land its Falcon 9, a re-usable rocket capable of sending satellites into space and back to base for a much lower cost. It has sovereign satellite constellation contracts with Greece and Spain, and also works for the UK — two satellites are monitoring extreme space weather events.

It has four strings to its space activities. The first is designing, launching and operating bespoke satellite communications services, data gathering and scientific research payloads. It also has a satellite management system that enables it to harness spare capacity of satellites owned by other parties, lowering costs. Last year it added analysis services to make more sense of the data it was collecting.

From the satellites it will manage by the end of the year, it will have the capacity to collect one billion square kilometres of data a year. “We can start to develop more sophisticated products that tell you, for instance, if there has been an oil spill in the middle of the Mediterranean or there are two vessels doing weird things in the Red Sea,” Jordá explains. The Ka-band licence enables it to offer broadband as well as narrowband services, meaning it could in future provide real-time communications to devices on the ground.

• European space lab sinks into black hole after UK pulls support

Jordá expects the company’s base in Harwell to expand by hundreds of people as a result of the licence win. “We need to keep scaling up our team and attract the top global talent,” he says. The UK space industry already supports more than 55,000 direct jobs, and Jordá would also like to see more money spent by UK and European governments. There have been mis-steps in the past. In 2020 the UK government invested £400 million on a stake in the failed satellite broadband firm OneWeb as part of a plan to replace use of the EU’s Galileo sat-nav system and to challenge Musk’s Starlink service. In 2022 OneWeb was acquired by the Paris-listed Eutelsat for a knockdown price.

But Jordá is adamant that, long term, building a domestic space industry will pay dividends. “In the US, it is insane the amount of procurement they have put from Amazon, SpaceX to really grow. I am not even saying the same order of magnitude, one order less across Europe and we would all be able to thrive.”

Explore the Sunday Times 100 Tech — interviews, company profiles and more