Reading Time: 9 minutes

Background – the new draft Climate Change Plan

The Scottish Government published its draft Climate Change Plan (CCP) on 6 November 2025, kicking off 120 days of parliamentary scrutiny. The draft CCP covers the period 2026-2040 across three ‘carbon budgets’. Carbon budgets set a legally binding cap on the maximum level of Greenhous Gas (GHG) emissions for a period of five years. In effect, a carbon budget is the amount of carbon that Scotland has available to ‘spend’ in a set time frame, like a personal budget for shopping. The Scottish Government has a goal of reaching ‘net zero’ GHG emissions by 2045.

The approach to reducing transport related GHG emissions set out in the draft CCP is largely focused on two areas:

- Encouraging and incentivising the rapid uptake of electric vehicles (EVs), as replacements for existing petrol and diesel vehicles, with a goal of all vehicles on the road being zero emission by 2040.

- Reducing private car use by a combination of policy ‘carrots’, that is improving alternatives to car use such as walking, cycling, and public transport, and policy ‘sticks’, physical or fiscal approaches which make car use less attractive, such as road space reallocation to buses, cyclists, and pedestrians.

The draft CCP predicts zero reduction in emissions from aviation and shipping over the three carbon budgets covering 2026-2040.

This post provides background on the first of these issues, EV uptake in Scotland, and considers relevant outcomes, policies and proposals set out in the draft CCP, challenges facing their delivery, and views expressed by stakeholders on the contents of the draft Plan.

What does the Draft Climate Change Plan say about electric vehicle uptake?

The draft CCP includes two transport ‘policy outcomes’ that are reliant on mass electric vehicle uptake. These are:

Transport Outcome 4: We will phase out the need for new petrol and diesel cars and vans by 2030.

Transport Outcome 5: We will work with the energy, finance and road transport sectors and related businesses to ensure all road vehicles are zero emission by 2040.

The delivery of these outcomes is supported by two EV focused ‘policy packages”. Transport Package 1– Measures to encourage uptake of Electric Vehicles (EVs) for cars and vans; and Transport Package 3: Measures to reduce emissions from Heavy Duty Vehicles. The ‘key policies’ within these two packages aimed at encouraging EV uptake are:

- The UK-wide Vehicle Emissions Trading Scheme (VETS) and the Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) mandate.

- The Scottish Government’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Fund.

- A new suite of Scottish Government consumer incentives to encourage electric car uptake.

- Investment in the replacement of diesel buses and Heavy Goods Vehicles (HGVs) and deployment of associated charging infrastructure.

- Energy market reform to support decarbonising transport, including HGVs.

- Support for electric vehicle skills development to support a just transition.

- Consideration and implementation of regulatory measures to encourage and ensure transition to zero-emission buses and HGVs.

Three of the mechanisms mentioned in these policies already exist, these are:

Zero Emission Vehicle Mandate: In January 2024, the UK Government introduced a zero-emission vehicle mandate for car manufacturers. The mandate specifies a minimum proportion of car manufacturers’ sales that must be zero-emission vehicles. This will rise from 22% of cars and 10% of vans in 2024 to 80% of cars and 70% of vans by 2030 and 100% of both in 2035. A series of flexibilities have recently been introduced to support domestic manufacturers during this transition, whilst maintaining the headline ZEV targets.

Vehicle Emission Trading Schemes (VETS): Accompanying the ZEV mandate are two VETS, these are:

- non zero emission car registration trading scheme (CRTS)

- non zero emission van registration trading scheme (VRTS)

These allow manufacturers to bank or trade ‘credits’ accrued by registering more zero emission vehicles, or fewer non-zero emission vehicles, than required under the ZEV mandate. Trading credits allows manufacturers to build more/fewer zero emission vehicles than set out in their ZEV mandate for a particular year within the envelope set out in the ZEV regulations.

Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Fund: Launched in 2022, the Scottish Government supports the expansion of the public EV charging network through the Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Fund, jointly developed and managed by Transport Scotland and the Scottish Futures Trust. The Fund originally aimed to deliver £60m of investment in the development of electric vehicle charging points between 2022-23 and 2025-26, with the Scottish Government investing up to £30m over this period, levering in another £30m of private sector investment. While it is unclear how much private investment has been ‘levered in’ Transport Scotland state:

Transport Scotland has provided £4.48 million to support development of strategies and procurement to all of Scotland’s 32 local authorities and has allocated a further £25.52 million of funding to local authorities and regional collaborations to support delivery of their public EV charging strategies. This means that the full £30 million of public funding available through the EV Infrastructure Fund has now been allocated to local authorities in Scotland.

The EV charging projects funded through the Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Fund are expected to be delivered between 2025 and 2030.

In addition to the charging infrastructure supported by the Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Fund, the Scottish Government announced a commitment in April 2024 to deliver 24,000 additional electric vehicle charge points by 2030, using a mix of public and private finance. Details of how these will chargers will be delivered are set out in a Draft Implementation Plan published on 16 December 2024.

With regards to the other key policies, the Scottish Government is yet to set out the terms of any new consumer incentives to support electric car uptake, the scale of future public investment in the replacement of diesel buses and HGVs and the deployment of associated charging infrastructure, the nature of energy market reform required to support road transport electrification, how it intends to support EV industry skills development, and the scope of any regulatory change required to support the switch to zero emission buses and HGVs.

Scope of expected emissions reduction

As shown in the table below (figures from the draft CCP), transport emissions reduction is heavily reliant on the speedy replacement of petrol and diesel cars, vans, trucks, and buses with zero emission equivalents, with the focus very much on electric cars.

The remaining reductions are largely from modal shift from petrol and diesel cars to active and sustainable modes and shifting freight transport from road to rail and water.

Transport related emissions reductions produced by CCP electric vehicle policies (reductions relative to CCC baseline figures)

2026-30

2031-35

2036-40

Measures to encourage EV take up

4.8 MtCO2e

13.8 MtCO2e

17.7 MtCO2e

Measures to reduce emissions from Heavy Duty Vehicles (HGVs and buses)

1.8 MtCO2e

2.8 MtCO2e

4.9 MtCO2e

Total CCP transport policy related emission reductions

7.5 MtCO2e

17.8 MtCO2e

23.8 MtCO2e

Proportion of total transport emissions reduction reliant on EV uptake

88%

93%

95%

A very small proportion of the GHG emissions reduction from Heavy Duty Vehicles may come from switching road freight to rail and water, rather than the adoption of electric HGVs.

The scale of the challenge

UK Department for Transport statistics show that at the end of June 2025 there were 2,620,200 cars registered in Scotland, of which 94,516 (3.6%) were battery electric, 46,864 (1.8%) plug-in hybrid-petrol, and a marginal number of plug-in hybrid diesel and range extended petrol engine cars.

Given that there is no expectation of a reduction in car numbers, over the next 15 years at least 2.5 million petrol and diesel powered cars in Scotland will need to be replaced with electric cars.

At the end of June 2025 in Scotland there were also:

- 13,000 buses and coaches, of which 817 (6.3%) were battery electric.

- 37,100 heavy goods vehicles, of which 40 (0.11%) were battery electric.

- 368,200 light goods vehicles (vans), of which 4,278 (1.16%) were battery electric and 355 (0.1%) were plug-in hybrid.

Researchers at the London School of Economics state that the median longevity of a petrol car in the UK is 18.7 years, which means cars being purchased now have a reasonable chance of still being on the road in 2040, the year by which the Scottish Government expects all vehicles to be zero emission. Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT) UK-wide statistics show battery electric vehicles accounted for 23.43% of all new car sales in 2025, with plug-in hybrids accounting for 11.14%. Petrol was still the most popular fuel type, accounting for 43.8% of all new cars sold in the UK during 2025.

Recent figures for zero emission vans and HGVs in Scotland are not readily available, but SMMT UK-wide figures show that during 2025 battery electric vans accounted for 8.7% of vans sold in the UK, with just 0.5% of new HGVs sold in the third quarter of 2025 being classed as zero emission.

As well as the practical challenges to achieving the rapid switch to EVs outlined above, and the financial challenges briefly outlined below, there are also significant consumer concerns to overcome. The most recent edition of Transport Scotland’s Transport and Travel in Scotland publication, dated 26 November 2025, reports the following result from the 2024 Scottish Household Survey question on electric car buying intentions:

The percentage of drivers saying they wouldn’t consider buying an electric car was 56% in 2024. This the highest percentage since the question was first asked in 2016. [Table 49]

When asked their reasons for not considering buying a plug-in electric car or van the most common answer given was the availability or convenience of charging points (52%), followed by cost of vehicle purchase (50%), and the battery (i.e. the distance that can be travelled on a charge) (49%) [Table 51].

Costs and who will pay them

The draft CCP only provides figures for ‘total benefits’ and ‘net CCP costs’ for each sector and broad groupings of policies and proposals. It does not set out details of expected total costs associated with policies and proposals, or any breakdown of where these costs fall, such as individuals, businesses, or the taxpayer.

Clearly, the cost of replacing the current Scottish vehicle fleet with electric cars, vans, trucks, and buses will run to many billions of pounds. This cost will largely be borne by individuals, businesses, and public sector organisations. This is not an unusual situation, as individuals and organisations expect to pay the costs associated with buying new or replacement vehicles. The main question is whether policies intended to encourage speedy EV uptake result in higher costs. While the cost of running an electric vehicle is typically less than that of a petrol or diesel vehicle, they are currently more expensive to buy. In addition, there is not a mature second-hand market for electric vehicles. The cost implications of mass electric vehicle uptake over the next 15 years are difficult to predict, as much is dependent on whether the cost of electric vehicles comes down to meet those of petrol or diesel equivalents and how the second-hand market develops.

The Scottish Government has committed to introducing a suite of consumer incentives to encourage the uptake of electric cars, plus support for zero emission buses and heavy goods vehicles. The scale and scope of these incentives and support, and the associated budget implications, are not set out in the draft CCP.

With regards the development the electric vehicle charging network, the CCP states that the creation of the slated 24,000 additional public charge points by 2030 will be “…largely funded and delivered by the private sector.”

Issues raised in the call for views

Over summer 2025, the Net-Zero, Energy and Transport Committee led a call for views on what people would like to see in the draft CCP. Respondents who commented on transport issues were unanimously supportive of the switch from petrol and diesel to electric vehicles, but did highlight several concerns, principally:

- Limitations on grid capacity could restrict the roll-out of electric vehicle chargers, restricting the ability of people to switch to electric EVs.

- The higher up-front costs of buying electric vehicles, when compared with petrol and diesel vehicles, acts as a disincentive to their purchase.

- There are skills shortages and supply chain issues affecting electric vehicle maintenance and charger installation.

Issues raised in oral evidence

The Net-Zero, Energy and Transport Committee questioned a panel of EV industry experts and an academic on the EV aspects of the draft CCP at its meeting of 16 December 2024, significant issues raised by witnesses during that meeting include:

- CCP targets for EV uptake will be very challenging to meet.

- Plans for 24,000 additional EV charge points to be installed by 2030 will be hard to deliver, with grid connections and the commercial viability of rural and island chargers being particular concerns. The public sector will likely have a significant, ongoing role in future delivery, which is not currently planned for.

- The Scottish Government needs to publish the assumptions behind the modelling of policy outcomes aimed at supporting EV uptake plus other supporting material to assist in the scrutiny and assessment of draft CCP policies and proposals.

- More detail is needed on plans for ‘consumer incentives’ to support EV uptake, again to support scrutiny and understanding.

- There is a need for multiyear funding streams and additional money for local government, so delivery bodies are assured of consistent funding availability to support mass EV use.

- The draft CCP focuses too heavily on swapping internal combustion cars with electric equivalents, with insufficient focus on reducing car use, redesigning places, and boosting public/active travel – which produce health and social equity as well as climate benefits.

- In addition to incentives to encourage EV uptake, it is also necessary to influence travel behaviour through mechanisms such as road user charging, street design, public transport service quality and integrated land-use/transport planning.

- Many households lack off‑street parking or easy access to EV charging, and that rural/low‑income communities, where charging infrastructure may be uneconomic to install/operate, risk being disadvantaged if policy centres on private EV ownership.

- There is a need for realistic, deliverable milestones and robust monitoring of EV uptake. This allows decision makers to pursue remedial action if policies fail to deliver expected outcomes within desired timescales.

Conclusion

There is strong support from transport stakeholders for the switch from petrol and diesel engined vehicles to electric equivalents set out in the draft CCP, although they have raised three main concerns:

- There is insufficient detail in the draft CCP to assess whether the policies and proposals are likely to deliver the stated outcomes.

- Targets for EV uptake, especially in the freight and bus sectors, will be challenging to meet.

- The draft CCP places too much emphasis on a like-for-like switch from petrol and diesel vehicles to EVs, which will do little to tackle issues such as traffic congestion, road collisions, and particulate pollution from tyres and brake discs. Greater emphasis should be placed on travel demand management, mode switch to walking, cycling, and public transport, and the role that could be played by technologies such as e-bikes (including e-cargo bikes).

Alan Rehfisch, Senior Researcher (Transport and Planning), SPICe

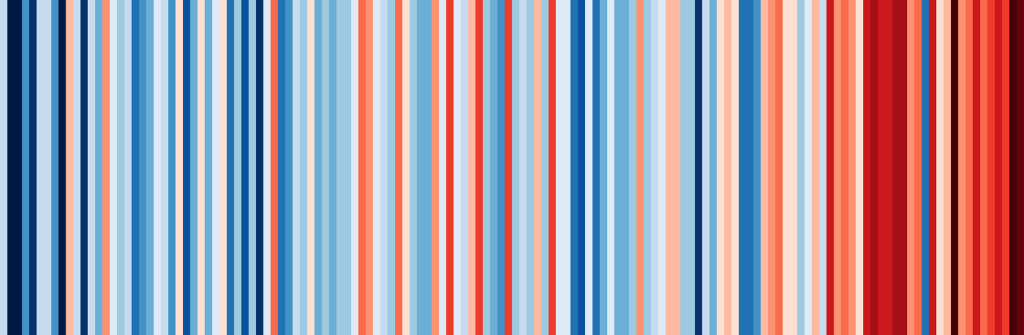

Featured image by Professor Ed Hawkins, University of Reading.

Like this:

Like Loading…