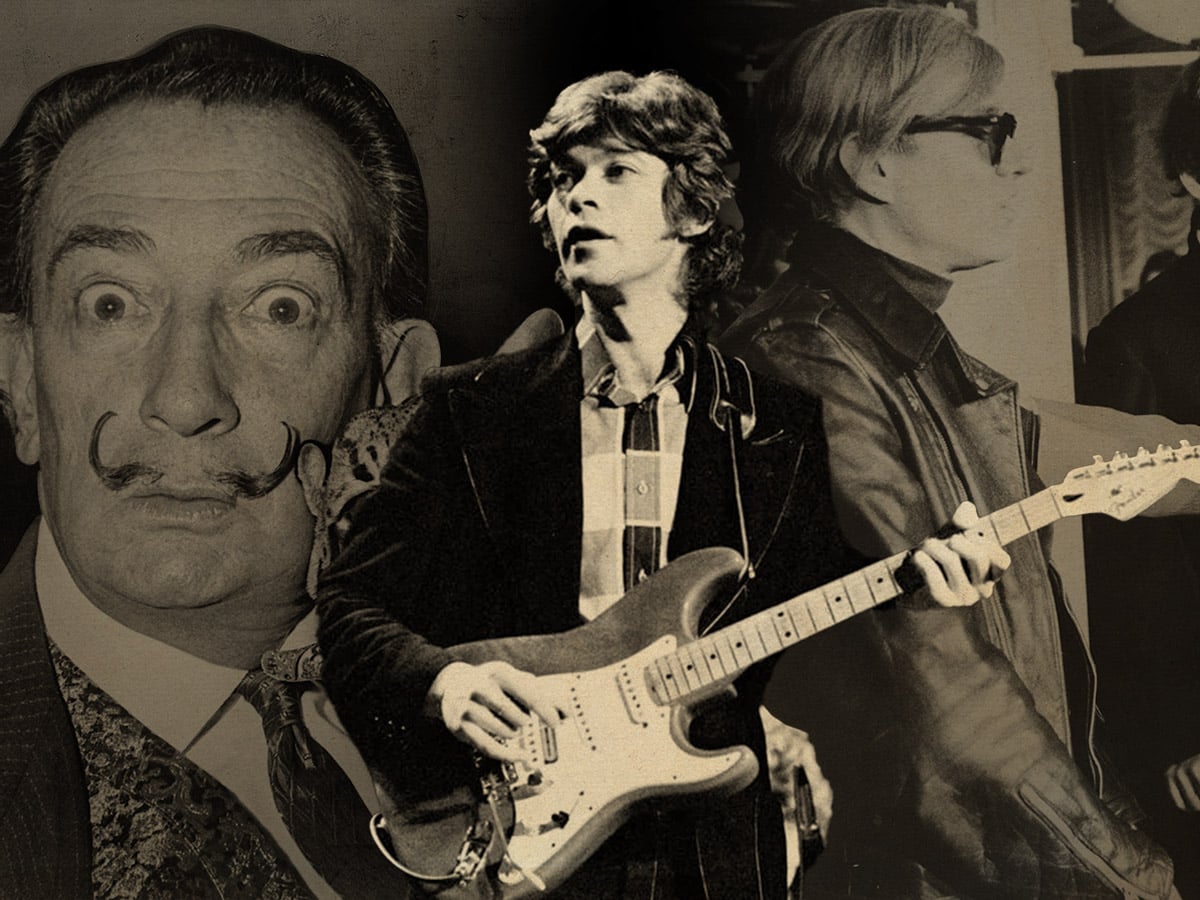

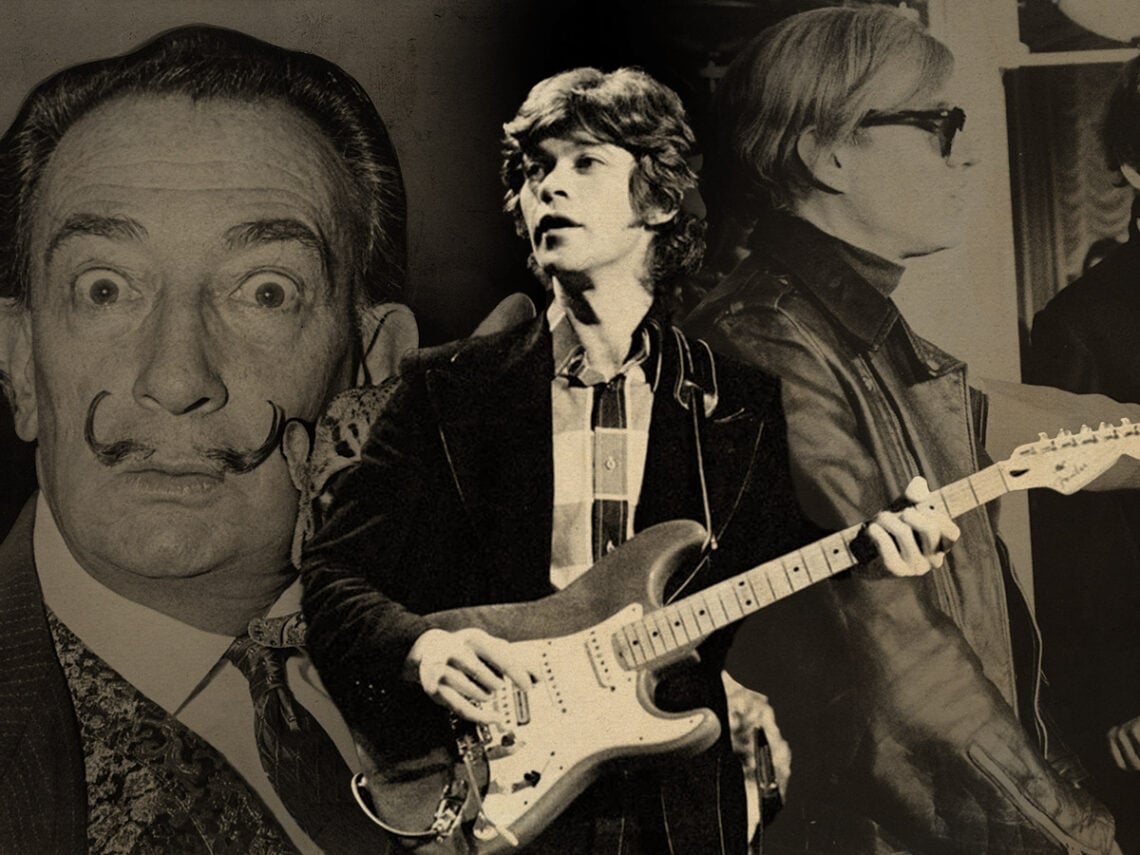

(Credits: Far Out / Alamy / James Kavallines / Roger Higgins)

Sat 17 January 2026 21:11, UK

It’s been decades since the 1960s, with new advancements, technology, cultural heroes, genres and styles having come through, but it still remains a period of complete obsession that especially grips music fans.

But then, when you hear a story like a random night Robbie Robertson spent in the company of the art world’s most enigmatic figures, it’s easy to understand why the fascination endures.

Sure, moments like this are still happening without us realising, as we’re living through history, and in 60 more years, some other journalist will sit here and write enamoured about artists at dinner parties, about meeting those who are modern and new to us, but who will one day be the old heroes. Albums being released this year might become classics that people obsess over and keep on repeat forevermore, as the fascination and intrigue will endure in the year 2076 as it does for us in 2026 for the bygone.

But somehow, it feels different; part of the reason why people remain so intrigued by the 1960s was that it sat on a precipice, where simultaneously, art and music were arguably the most lucrative they had ever been, but also the most lawless. Moreover, the idea of the ‘industry’ didn’t come into it, and artists could be artists, with the scene ruling supreme as some of culture’s best stories, best collaborations and best work all just came from the meeting of minds at some party or another. One chance encounter could change it all, and the people we now worship were out there partying, that’s for sure.

In this story, the party was in New York City, amongst one of the most rose-tinted chapters in history, the Chelsea Hotel era, where the most important artists around took up a room in the same space; it was a time when Andy Warhol was at the height of his power, and the city was alive with the sound of The Velvet Underground, Bob Dylan and the slow dawning of the punk age, so naturally Robbie Robertson was right in the thick of it.

Around 1966, he was playing as Bob Dylan’s backing band as well as crafting his own outfit, ingeniously titled The Band, so, in short, he was in the big leagues and was having a lot of fun with it, taking up residence at the Chelsea and thriving amongst the riff raff.

Though Dylan still loves to deny it, there was one key character revolving around their realm at that time, and that was Edie Sedgwick. Inspiring songs on Blonde on Blonde, Andy Warhol’s ultimate superstar seemed to have that whole set wrapped around her finger as even Robertson admitted of their own relationship, “I wouldn’t say we dated, but sometimes she didn’t want to be alone”.

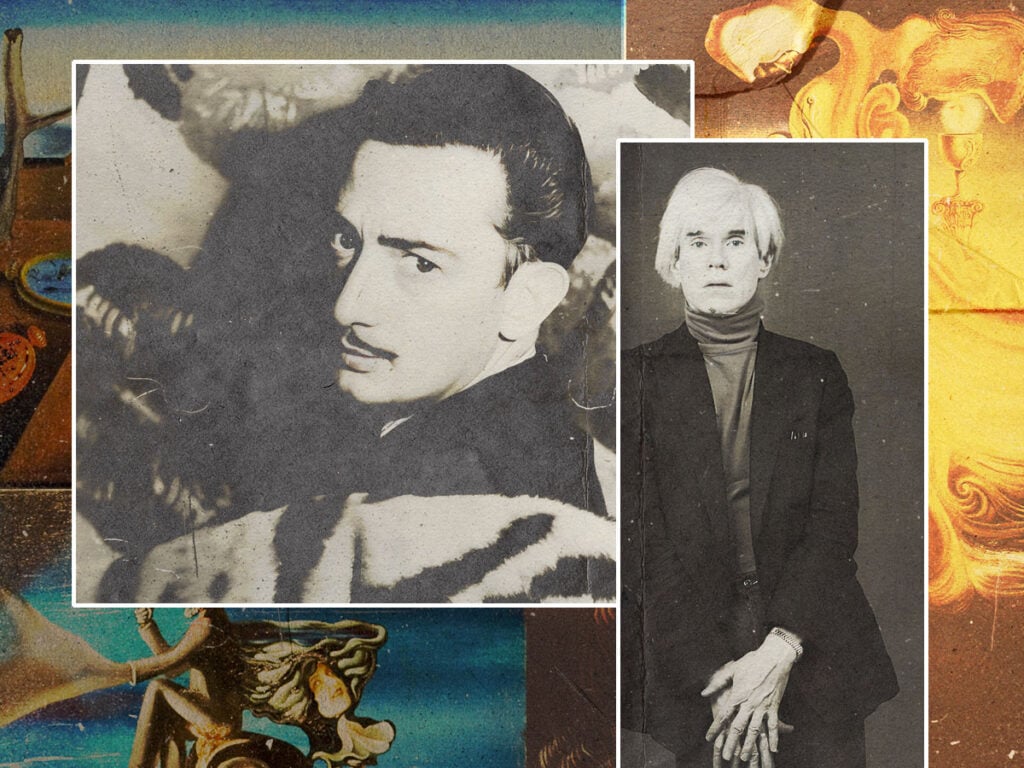

Saldavor Dalí and Andy Warhol, two of art’s most enigmatic figures. (Credits: Far Out / Alamy / National Galleries of Scotland / Flickr)

Saldavor Dalí and Andy Warhol, two of art’s most enigmatic figures. (Credits: Far Out / Alamy / National Galleries of Scotland / Flickr)

Dylan famously hated Sedgwick’s counterpart, but Robertson didn’t seem to mind Warhol so much, happily going along with him and Sedgwick to whatever wild party they might be heading to, and in this case, the gathering was hosted by Salvador Dalí.

Clearly seeing that NYC was the place to be, Dalí had set up residence at the Regis Hotel on 55th Street and Fifth Avenue, and one night, when Robertson, Sedgwick and Warhol found themselves there, they noticed some half-finished sketches on the table of some horses.

Something about them seemed to move Warhol, about which Robertson recalled, “Andy said, ‘Maybe I should do a horse’”. However, in a drunken stupor in the strange atmosphere of a soiree of some of history’s most volatile and electric figures, Dalí seemed to be very anti that idea, as he retorted, according to Robbie, “Salvador said, ‘You don’t need to do horses. You have ladies’ shoes and soup cans’”.

Tensions rose, and Warhol boiled over, leading to a baffling stand-off as the musician recalled, “Andy said, ‘I think we should go’. Salvador was, like, ‘You must never go! You must never leave!’”

The thing was, Warhol had already done plenty of horses; he drew a bunch of them, he made a film of one, he’d go on to make even more horse prints later on. The horse really makes no difference here, and chances are, by the next morning, neither Warhol nor Dalí remembered the interaction, or cared at all if they did. The key is simply this: while all this was going on, Robertson was just there, witnessing an odd moment between two figures already destined to be remembered forever, and all he could think was, “Wow, it’s a Salvador Dalí moment”.

Related Topics