Margam Castle, Margam Country Park. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Margam Castle, Margam Country Park. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Archaeological surveys beneath a park in south Wales have revealed the remains of a substantial Roman building, despite no surface evidence of occupation.

Beneath Margam Country Park, on the outskirts of Port Talbot, lies the largest Roman villa yet identified in Wales. The discovery came from ground-penetrating radar, which traced walls and rooms hidden for more than 1,500 years.

“My eyes nearly popped out of my skull,” said Dr. Alex Langlands, the project lead, after seeing the scans, in comments to BBC News.

Archaeologists have playfully dubbed the site “Port Talbot’s Pompeii.” The comparison is not about volcanic ash. It is about the pristine level of preservation. Like Pompeii, this place appears to have been spared the slow destruction that usually erases ancient buildings from the landscape.

Roman Wales has often been portrayed as a militarized frontier, dominated by forts, roads, and marching camps. A grand rural estate suggests something else entirely.

Not Just a Frontier Town

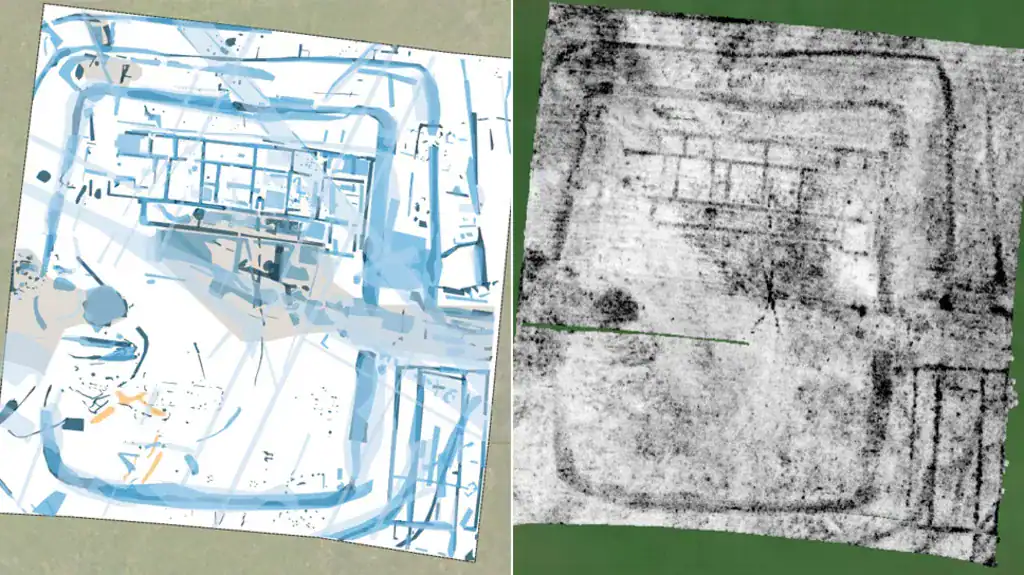

The scans revealed a villa within a defensive enclosure and an aisled building, possibly used as a barn or meeting hall. Credit: TerraDat Geophysics

The scans revealed a villa within a defensive enclosure and an aisled building, possibly used as a barn or meeting hall. Credit: TerraDat Geophysics

The geophysical surveys show a large corridor villa set inside an enclosure measuring about 43 by 55 meters. The layout includes a long central range with wings and multiple rooms, and a veranda running along the front. To the southeast stands another substantial building, possibly a barn or a meeting hall.

In total, the main villa covers about 572 square meters. That makes it the largest standalone Roman villa yet identified in Wales.

In Roman Britain, villas of this scale were the administrative and social centers of large agricultural estates. Grain, livestock, and labor flowed through them, supporting both local elites and the wider imperial economy.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

Until now, most Roman remains in Wales have been military. Civilian estates like this are rare.

The researchers used ground-penetrating radar to survey the ‘footprint’ of the Roman villa. Credit: Hazel Langlands

The researchers used ground-penetrating radar to survey the ‘footprint’ of the Roman villa. Credit: Hazel Langlands

“Until now, Wales in the Romano-British period has, for the most part, been about legionary forts,” Langlands told The Guardian. “It’s always been around conquest.”

The Margam villa points in a different direction. Its scale and design resemble high-status villas in Gloucestershire, Somerset, and Dorset—areas long seen as the prosperous heartlands of Roman Britain.

“This wasn’t necessarily a frontier zone, an unstable place,” Langlands added. “It suddenly feels like we were less out on some windswept frontier.”

The site may date to the fourth century, a period when rural elites across Britain invested heavily in luxurious homes even as Roman political control began to fray.

A Protected Site

Artist’s interpretation of the late 4th-century Lullingstone villa in Kent. Margam’s villa may have been similar. Credit: Peter Urmston/English Heritage

Artist’s interpretation of the late 4th-century Lullingstone villa in Kent. Margam’s villa may have been similar. Credit: Peter Urmston/English Heritage

The villa survived because the land above it was left alone. Margam has been a deer park for centuries, perhaps stretching back to Roman times. The ground was never intensively ploughed, sparing buried walls and floors from destruction.

The radar scans suggest that floor surfaces and wall foundations remain intact. Christian Bird of TerraDat, the company that carried out the survey, said the images were “remarkably clear, identifying and mapping in 3D the villa structure, surrounding ditches and wider layout of the site,” as per BBC News.

Archaeologists are keeping the exact location secret to protect it from illegal metal detecting. For now, the focus is conservation, followed by further surveys and, eventually, excavation.

The discovery also has implications beyond archaeology. Langlands has suggested that Margam may have been a major local power center and has speculated that it could even have lent its name to Glamorgan, the historic region of south Wales.

The project, led by Swansea University with local partners, has involved school pupils and community members from the start. An open day at Margam Abbey Church will share more findings later this month.