An international research team has discovered an unusual quasar in the early Universe. It contains one of the fastest-growing supermassive black holes.

The mystery of supermassive black holes

At the centers of most galaxies are supermassive black holes, whose mass is millions and billions of times greater than that of the Sun. They grow by pulling in surrounding gas. The gas, spiraling inward, forms an accretion disk and may also feed a compact region of hot plasma known as the corona (a key source of X-ray radiation). In some cases, polar jets are also formed, which emit strong radio waves. The brightest and most actively feeding black holes are called quasars.

Supermassive black hole in an artist’s impression. Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Supermassive black hole in an artist’s impression. Source: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Although astronomers understand how supermassive black holes feed, a fundamental mystery remains. Observations indicate that they existed in the early Universe shortly after the Big Bang. This raises the logical question of how such objects could have formed so quickly.

13 times the growth limit

The leading idea behind rapid early growth is the so-called super-Eddington accretion. In standard theory, radiation produced by matter falling into a black hole repels gas and sets an upper limit on the growth rate, called the Eddington limit. But under special conditions, black holes can temporarily exceed this limit, allowing them to rapidly increase their mass over short intervals of time by cosmic standards.

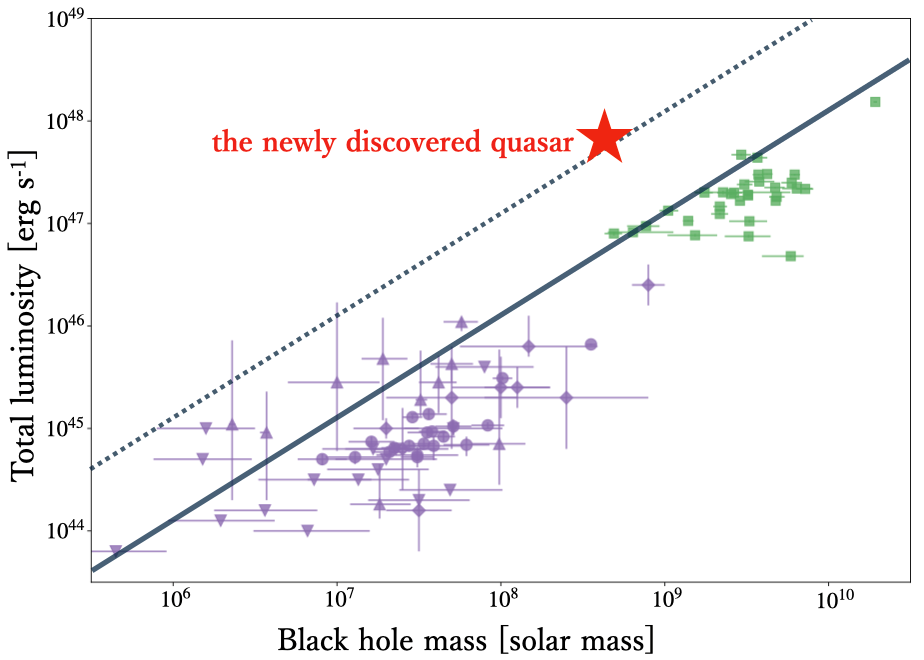

Quasar luminosity (vertical axis), which reflects the growth rate of the black hole, compared to the mass of the black hole (horizontal axis) for the newly discovered quasar eFEDS J084222.9+001000 (red star) and previously observed objects (purple and green symbols). The solid line indicates the theoretical upper limit of black hole accretion rate (Eddington limit), while the dotted line indicates gas accretion ten times higher than this limit. Precise measurement of the black hole’s mass showed that eFEDS J084222.9+001000 exhibits super-accretion exceeding the Eddington limit. Source: NAOJ

Quasar luminosity (vertical axis), which reflects the growth rate of the black hole, compared to the mass of the black hole (horizontal axis) for the newly discovered quasar eFEDS J084222.9+001000 (red star) and previously observed objects (purple and green symbols). The solid line indicates the theoretical upper limit of black hole accretion rate (Eddington limit), while the dotted line indicates gas accretion ten times higher than this limit. Precise measurement of the black hole’s mass showed that eFEDS J084222.9+001000 exhibits super-accretion exceeding the Eddington limit. Source: NAOJ

To verify whether such extreme growth occurred in the early universe, scientists used the Subaru telescope to measure the motion of gas near the quasar eFEDS J084222.9+001000, which existed 12 billion years ago. Observations showed that the accretion rate of its black hole is about 13 times higher than the Eddington limit.

What makes this quasar particularly striking is that, despite its extremely rapid accretion, it shines brightly in both the X-ray and radio bands. These features contradict current theoretical models and point to the existence of as yet unknown physical mechanisms.

One hypothesis suggests that we are observing the quasar during a brief transitional phase, for example, following a sudden surge in gas inflow. Thus, a rapid surge in accretion could have pushed it into a super-Eddington state while maintaining a bright X-ray corona and powerful jets. The quasar will subsequently transition to a more typical mode.

If the assumption is correct, the discovery provides a rare opportunity to observe temporal changes in the growth of black holes in the early Universe. This is an important step toward understanding how such objects formed so quickly.

According to Subaru Telescope