Share

Share

Or

https://www.archdaily.com/1038070/the-chromatic-canvas-10-vibrant-courts-activating-community-space

Unlike most popular sports, the origin of basketball has a precise year and creator: it was invented in 1891 in the United States by Canadian physical education instructor James Naismith as an indoor sport for athletes at Springfield College during the winter, after the end of the football season. The sport quickly expanded beyond U.S. borders, being included in the Olympic Games in 1936 and achieving international popularity after the Second World War. As basketball became more widespread, it also left the controlled environment of gymnasiums and began occupying a wide range of locations: playgrounds, public plazas, school courtyards, driveways, and backyard patios became informal courts for play and community life, reinforcing the role of physical activity as a catalyst for social interaction and neighborhood regeneration.

Part of this widespread popularity is due to the sport’s adaptability and the fact that very little is needed to play it: just a ball, a basket, and a flat surface. Basketball adapts to almost any available geometry – from improvised courts painted on asphalt to fenced courts found in public squares or community centers – allowing the game to thrive across socioeconomic and geographic boundaries.

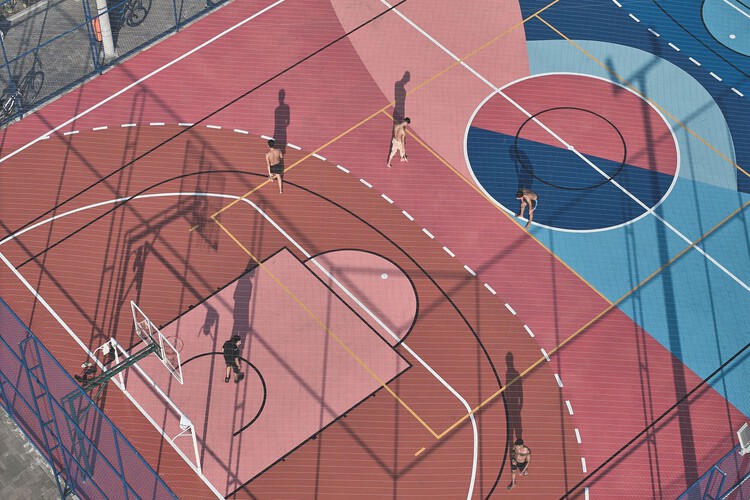

As basketball migrated into urban outdoor spaces, the court became more than just an athletic infrastructure – it transformed into a civic surface. Today, color plays a central role in this shift. Vibrant chromatic palettes activate courts visually, signaling that these are spaces meant to be occupied, shared, and collectively experienced, whether as a player or as a spectator.

Related Article Transforming Public Spaces Through Art: An Interview with Antonio Ton

The colorful courts presented below illustrate how sport and thoughtful design strategies can foster social proximity. They operate as magnets, attracting children and adults, locals and tourists, players and spectators alike, and drawing them into dialogue with one another. The chromatic surface becomes a visible signifier of public life – one that helps communities reimagine their surroundings through play.

Huachiao Vibrant Sports Park / SoBA © HoliBlue Court / Found Projects + Atelier Noirs

© HoliBlue Court / Found Projects + Atelier Noirs © Atelier NoirsHousing Unit Infonavit CTM Culhuacán Square / AMASA Estudio, Andrea López + Agustín Pereyra

© Atelier NoirsHousing Unit Infonavit CTM Culhuacán Square / AMASA Estudio, Andrea López + Agustín Pereyra © Zaickz Moz, Andres Cedillo, Gerardo Reyes BustamantePlayón Red Public Spaces and Community Infrastructures for Integration / Región Austral

© Zaickz Moz, Andres Cedillo, Gerardo Reyes BustamantePlayón Red Public Spaces and Community Infrastructures for Integration / Región Austral © Luis BarandiaránParque Rita Lee – Legado do Parque Olímpico / Ecomimesis Soluções Ecológicas

© Luis BarandiaránParque Rita Lee – Legado do Parque Olímpico / Ecomimesis Soluções Ecológicas © Rafael SalimOlympic Neighborhood Square / Región Austral + CEEU

© Rafael SalimOlympic Neighborhood Square / Región Austral + CEEU © Luis BarandiaránPigalle Duperré / Ill-Studio

© Luis BarandiaránPigalle Duperré / Ill-Studio © Sebastien MicheliniUH Infonavit Santa Fe Community Park / AMASA Estudio

© Sebastien MicheliniUH Infonavit Santa Fe Community Park / AMASA Estudio © Zaickz MozPavuna Park / Embyá – Paisagismo Ecossistêmico

© Zaickz MozPavuna Park / Embyá – Paisagismo Ecossistêmico © Douglas LopesSpark Pavilion / ATMOperation

© Douglas LopesSpark Pavilion / ATMOperation © ACF

© ACF

This article is part of the ArchDaily Topic: Coming Together and the Making of Place. Every month we explore a topic in-depth through articles, interviews, news, and architecture projects. We invite you to learn more about our ArchDaily Topics. And, as always, at ArchDaily we welcome the contributions of our readers; if you want to submit an article or project, contact us.