His shoes were shined for the High Court, the home from home these days for the Duke of Sussex, who is no stranger to litigation since leaving the royal fold.

In court 76, Prince Harry stretched his neck down to both shoulders, limbering up for battle with Associated Newspapers Ltd (ANL), the publisher of the Daily Mail and Mail on Sunday, over allegations of unlawful information gathering, which are vehemently denied by ANL.

It is a battle, alongside Sir Elton John, Elizabeth Hurley, Baroness Lawrence of Clarendon and three others, that Harry claimed he could never fight as a member of the “institution”, the chilly phrase he now uses to describe his family.

Prince Harry leaving court after giving evidence

JOSHUA BRATT FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES

On the stand, he explained that, in his former life as a working royal, he was bound by the institution’s “never complain, never explain” mantra, forced like the rest of his family to put up and shut up.

But some recollections may vary. The King and the Prince and Princess of Wales have fought and won legal battles for invasions of privacy — Charles over the Mail on Sunday’s publication of extracts of his private diaries in 2005, William and Kate over photographs of the couple holidaying in France published in the French magazine, Closer, in 2012 and, last year, for photos published in Paris Match of their family skiing holiday in Courchevel, France.

As for Harry’s claim that he was “not allowed to complain” inside the institution, the history books again tell a different story. Harry’s grievances were given plenty of airtime by courtiers, memorably in November 2016 when he directed his communications secretary to issue a highly charged statement about the treatment of his new girlfriend, Meghan Markle, attacking a “wave of abuse and harassment” by the media. Issued while Charles was on an official visit to Bahrain and blowing his father’s coverage out of the water, it was hardly the action of a prince shackled by royal protocol.

Here is a central mission of Harry’s media crusade. Terse and tearful under cross-examination on Wednesday, he painted a picture of the most reluctant royal. Before he left these shores with Meghan for California in 2020, he said his years in the royal fold were marred by the pretence of being “forced to perform” for the press at events, despite his “uneasy” relationship with them. “There was no alternative,” he said. “I was conditioned to accept it.”

Much of being a member of the royal family is a performance — on palace balconies, on overseas tours, while hosting controversial heads of state with a game face on. Of all the royals I’ve watched over the years, Harry was best at winning performances and media stunts, ensuring maximum coverage for the family business and his own causes.

For the most part, he looked like he enjoyed it. If high jinks in Jamaica sprinting with Usain Bolt on a tour honouring Queen Elizabeth’s diamond jubilee in 2012 were performed under duress for the media, then we were all fooled.

If the “mic drop” video with granny and the Obamas, which marked Harry’s 2016 Invictus Games in Orlando, Florida, was performed for the press against his will, then he’s a much better actor than I thought.

“Hindsight is a beautiful thing, Mr White,” Harry told Anthony White KC, who was defending ANL in court. There is hindsight, and then there is revisionist theory. Come on, Harry, admit it — you were very good as a professional prince, and you didn’t hate every single second of it.

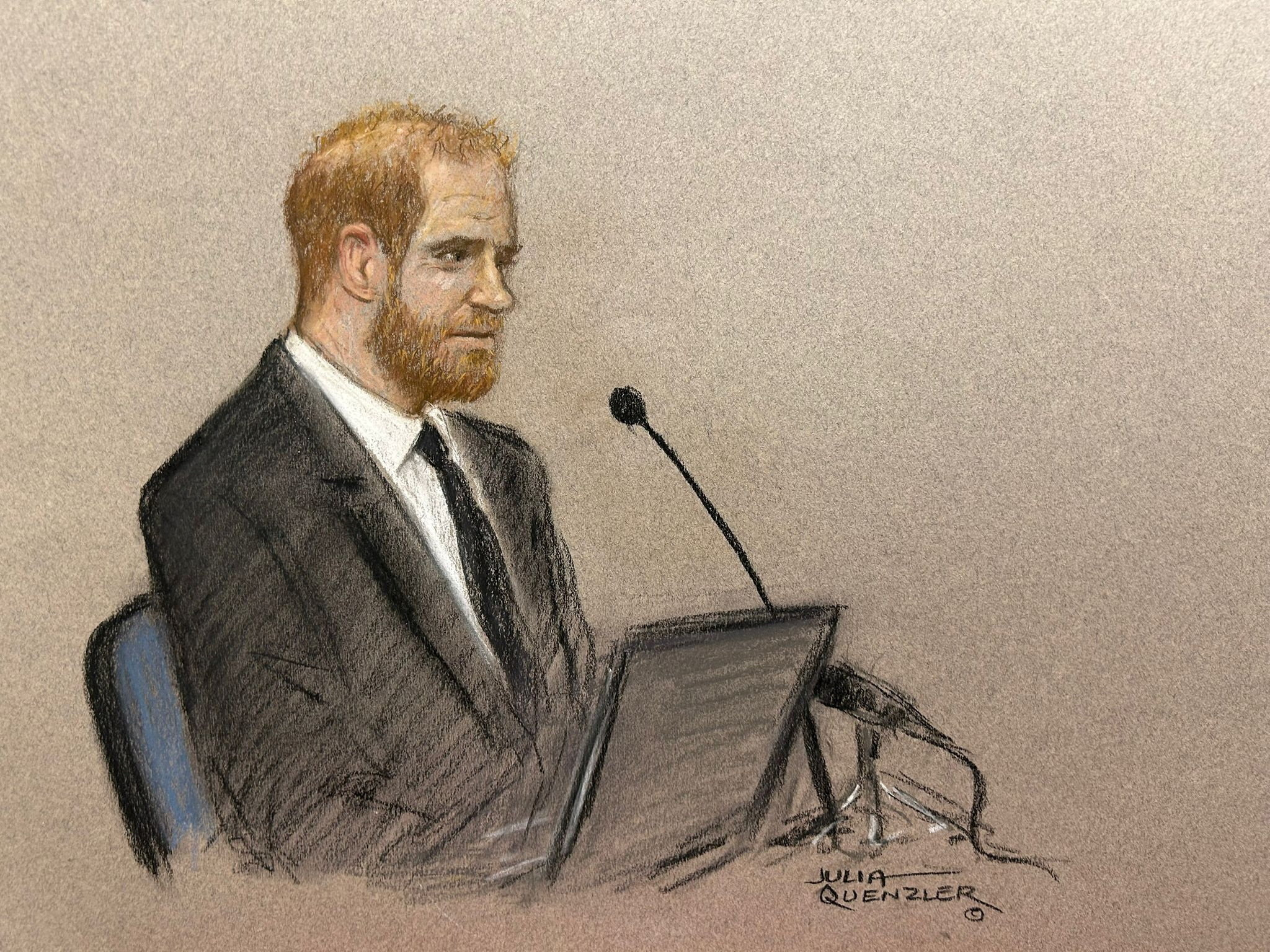

Harry gives evidence at the High Court

JULIA QUENZLER/REUTERS

As for the duke’s witness statement that his treatment by the media “feels like every aspect of your life behind closed doors is being displayed to the world for amusement, entertainment and money”, and his witness-box broadside that “I’ve never believed my life is open season to be commercialised by these people [the media]”, imagine how those declarations landed with the rest of his family.

After penning a bestselling memoir that revealed many of his family’s most private moments, a back catalogue of splashy interviews with Oprah Winfrey, and a tell-all Netflix documentary, Harry has commercialised much of his private life and — without their permission — his family’s.

It is hard to deny Harry the right to feel bitter towards the media, when he blames the media for his mother’s tragic death in 1997. The image of Princes William and Harry, aged 15 and 12, walking behind Diana’s coffin, is seared into the public’s consciousness.

His angst, years later, when former girlfriends and his wife felt similarly “hunted”, is understandable and pushed him towards the California emergency exit. But it is for Mr Justice Nicklin, not Harry, to determine if ANL pushed the boundaries beyond the law.

Harry says he just wants “an apology and some accountability”. But is that really all he wants? Because, watching him in court, it felt like there was another agenda at play: that he wants us to believe he was never a happy prince.

If his ambition really is to wipe clean the memory of a prince who once relished his role, he may soon achieve it in the court of public opinion. The image of happy Harry is fading from view. But what a shame it will be if the once cheerful prince, who did so much good inside the royal fold, is forever remembered outside the institution as a disgruntled duke.