No sport preys on nostalgia quite like boxing. Whether an exhibition bout mooted for March in Africa between Mike Tyson and Floyd Mayweather, who is 11 years younger and seven stone lighter, comes to fruition remains to be seen, but stranger things have happened.

In fact they already did the last time Tyson, 59, hobbled into the ring, sporting a knee brace, months after a stomach ulcer flare-up that required eight blood transfusions. “I almost died,” Tyson revealed — only after his haggard ghost had been beaten up by the Disney star turned boxer Jake Paul.

For those whose celebrity is less enduring, the yearning for one last payday can lead to darker and more dangerous corners. Towards the end of last year, at Trilogy Nightclub in Colchester, Essex, Danny Williams climbed wearily through the ropes. The MC introduced him as the former British and Commonwealth heavyweight champion, an inarguable truth, albeit one that overlooked the fact Williams has not held one of those titles for 16 years.

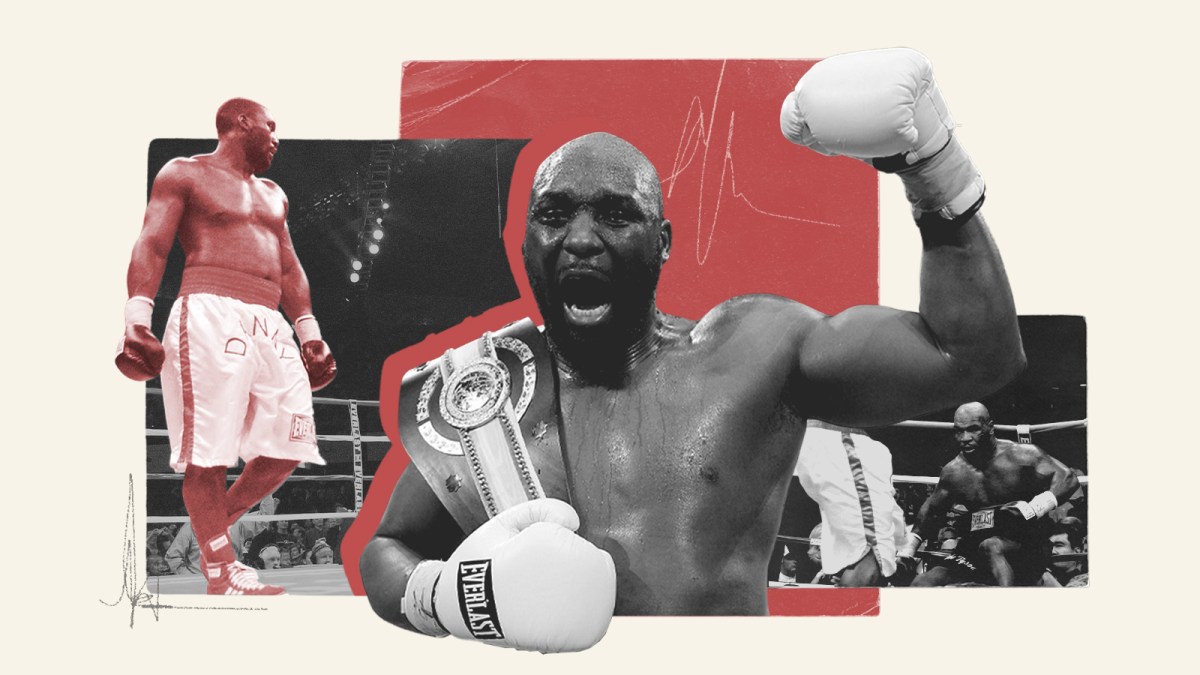

But his real claim to fame, and the reason why about 200 punters had parted with £35 to attend, is his involvement in one of British boxing’s greatest upsets, when he beat Tyson in 2004.

Footage of the Essex Boxing Organisation event quickly becomes difficult to watch. Williams, 52, still appears in good physical condition, but his expression is absent and forlorn. Early on Tony Conquest, 41, lands a shuddering one-two with Williams pinned against the ropes.

The pattern continues in painful slow motion, with Williams offering little response before he is caught heavily again in the closing seconds and the bell saves him.

Please enable cookies and other technologies to view this content. You can update your cookies preferences any time using privacy manager.

Enable cookiesAllow cookies once

Back in the corner, Williams’s coach pulls him out of the fight. He feigns no protest, nor gives any interviews. Instead, the fight’s promoter, Tommy Jacobs, who was sentenced to 12 years in prison in 2009, tells the crowd what he just told Williams: “Don’t ever f***ing do this again. Enough is enough.” The trouble is, in a sport as anarchic as boxing, there are not sufficient laws to stop him.

Tyson’s might had been blunted by years of ill discipline when he fought Williams at the Freedom Hall State Fairground in Louisville, Kentucky, but the bookmakers still made him a 1-9 favourite. Yet Frank Warren, then Williams’s promoter, was adamant that if his charge could weather an early barrage, they may pull off a remarkable upset.

That prediction came true as Williams was shaken and staggered in the first round but, by the fourth, Tyson, who had badly injured his left knee, was a spent force and Williams sent him to the canvas with a 26-punch fusillade. “It was a great moment in some ways but, in others, it was a shame because it prolonged his career,” Warren says. “Because he’s got that win over Tyson, it’s seen as a selling point to put him in with up-and-coming fighters [overseas] or on these unlicensed shows.”

One of the most liked men in British boxing had beaten the so-called baddest man on the planet. Warren describes Williams as a “very quiet, gentle person”. Born in Brixton, south London, in 1973, some of his friends had turned to crime and been killed or sent down but Williams separated himself from that, bashing away on the punchbag his father installed in their back garden.

He earned about £140,000 for his victory over Tyson and nearly four times that for his next fight, against Vitali Klitschko for the WBC title in Las Vegas. Although Williams was thoroughly beaten, he should have been able to retire with his future relatively secure. Instead he ploughed on, fighting domestic rivals on undercards, even in leisure centres. After a gruesome defeat by Derek Chisora in 2010, it seemed that the 36-year-old was finally ready to accept retirement, but the lure of prizefighting can be as addictive as it is dangerous.

“He retired but then he reapplied for his licence and we refused it. We were concerned by his performances, and I told him to look after his family and that he’s had a very good career,” says Robert Smith, general secretary of the British Boxing Board of Control (BBBofC). “The biggest problem is there is no world governing body, so you can go and get a licence from anybody, and so he mainly went to eastern Europe. We did notify the European Boxing Union on a number of occasions that he shouldn’t be boxing, but it didn’t make a lot of difference.”

Since 2010, Williams has been in 38 professional bouts, according to the database Boxrec. After fighting in more established boxing destinations such as Germany and Russia, he then ventured seven times to the Czech Republic over five years, beginning in 2013. Then it was Hungary, Austria, Kazakhstan, Latvia and Albania. Promoters often put Williams in with inadequate journeymen, seemingly in a bid to improve his standing or simply as a circus act, before leaving him to the mercy of their young hope.

A lucrative fight against Klitschko should have left Williams financially secure more than 20 years ago

ED MULHOLLAND/WIREIMAGE

The last two fights on Williams’s record took place in Estonia in 2023 and followed that formula, leaving him with 55 wins and 33 losses (17 by knockout). When he first retired in 2010, it had been 41-8, and there are likely to be more unlicensed contests that do not appear on his record, such as that bout in Essex in late October.

While the BBBofC is the recognised professional governing body in Britain (England Boxing, Boxing Scotland and Welsh Boxing oversee the amateur sport) and ensures that boxers pass an annual medical before being granted a licence, there is little to prevent someone from putting on a boxing show outside that framework.

A paper published by Sheffield Hallam University last year found that of 500 coaches surveyed, half knew of colleagues involved in white-collar boxing and more than 75 per cent thought boxers were being mismatched in terms of training, experience, weight and age. Furthermore, 54 per cent of the coaches cited a lack of appropriate medical care at such events.

Jacobs, 39, founded the Essex Boxing Organisation in 2015 shortly after he was released from prison, having served six years of his sentence for wounding with intent. He says he has staged “what some people call white collar, what some call semi-pro, what some call unlicensed shows — that fringe between professional and amateur” on a regular basis and that “safety is always paramount”.

Jacobs also claims that Williams had “done his proper medicals and passed them with flying colours” via an event security firm, Overguard Security, whose personnel “were at ringside and did post-fight checks etc”.

A 36-year-old Williams was knocked down twice by Chisora in 2010. He retired shortly afterwards but then returned to the sport and has fought nearly 40 times since — not including unlicensed bouts

NEWS GROUP NEWSPAPERS LTD

Overguard Security said its personnel were not on the ground as Trilogy Nightclub has an in-house security team, but that it did carry out medical checks via a specialist third-party provider. Jacobs claimed they were “the same, if not more thorough than what the BBBofC does”. However, the board’s medicals are first carried out by GMC-registered doctors and then double-checked by their own, and Smith reiterated that the board would never have approved Williams to fight.

Jacobs said there was no ringside doctor present because it was “basically an exhibition”. As Jacobs describes it, it was agreed that Williams would be pulled out after the first round and that Conquest was “not going to throw proper punches. If he does, it’ll be arm shots, things like that”.

Williams’s profile would help sell the tickets and earn him a small purse, probably in the low four figures, while Conquest’s win could secure him a better fight. As part of the deal, Jacobs says, he also became Williams’s manager, so that he could reject requests from promoters attempting to capitalise on Williams’s name.

“I said, ‘Look, we’ll get you for a round, make it look decent for the people that are there so Tony’s supporters don’t feel duped, and get you a little payday, but only on the basis that you’d never box again,’ ” Jacobs says. “ ‘Leave the sport now with whatever faculties you’ve got intact.’ ”

Williams is stopped after one round in Colchester late last year, with no ringside doctor. Jacobs says it was arranged that the 52-year-old would withdraw at that stage

Jacobs says that Williams had two more fights planned for November, in Bosnia and Turkey, but that both were cancelled. He estimates that Williams would have been paid only £1,000 plus expenses for each and nobody would “give an absolute monkey’s” about his health. “I could tell enough stories to close down about half of the European boxing committees because some of them are atrocious,” he says.

But the unregulated circuit in the UK is little better. “Unlicensed boxing has its connotations,” Jacobs says. “Most people think it’s in a field between haystacks with a load of gypsies. Some of these shows are incredibly safe. Some of them are awful. A lot of them are, in fact, and an awful lot of people have died.”

Warren, Wiliams’s former promoter, thinks that “at one stage Williams didn’t even want to be a boxer”

ANDREW BOYERS/REUTERS

Williams rejected multiple interview requests and the chance to talk about why he is still fighting. It was rumoured that he was financing his two daughters’ private-school education, but they are both in their twenties now. Spencer Fearon, a childhood friend who worked as Williams’s cornerman and adviser, said the subject was “too painful to speak about” and that he would not want anything he said to be “misinterpreted as any form of disrespect”.

Wayne Alexander, another close friend and a former European super-welterweight champion, also declined to speak. Jacobs had previously employed Alexander as a referee on his Essex Boxing Organisation shows, but Alexander said he would not be involved if Williams was going to be fighting.

There is little else Williams’s friends or the boxing fraternity can do to dissuade him. Warren recalls one night early in Williams’s career when he refused to leave the dressing room at York Hall in Bethnal Green, east London, moments before he was due to fight an obscure, undermatched opponent. Nobody imagined then that Williams would go on to defeat Tyson, let alone that two decades later that defining night would be the albatross around his neck.

“Danny’s a really lovely bloke. At one stage, I didn’t think he even wanted to be a boxer,” Warren says. “It’s crazy what’s happening and it shouldn’t be allowed. Every punch he takes is brain damage. The problem in this day and age is it just seems like it’s never going to stop.”

The BBBofC and the national amateur governing bodies are lobbying the DCMS to legislate that competitors in unlicensed bouts should, at the very least, be affiliated to a club, but progress has been slow and the board is essentially helpless to stop anybody fighting in the meantime.

Jacobs remains Williams’s manager and appears to have been true to his word, insisting there are no plans for future fights. But Williams’s case is sadly just one of the most striking examples in a sport littered with them.