“The war on drugs has failed,” Zack Polanski told reporters in October 2025. The new leader of the Green Party for England and Wales, rising in the polls after his appointment, called for legalization and a drug-policy approach “led by public health experts, not politicians.”

The backlash was swift and brutal. Polanski’s support for the regulation of substances like cannabis and MDMA was “reckless,” according to media commentators. And prescribed heroin on the National Health Service? “State-sponsored drug taking.”

Britain’s prohibitionist drug policies are now so deeply entrenched that it’s hard to believe it was long a world leader in what would now be called safe supply.

From 1926, doctors were legally allowed to prescribe pharmaceutical heroin (diamorphine) and other opiates to patients with dependencies. This followed the publication of a landmark report by Sir Humphrey Rolleston, former president of the Royal College of Physicians and chair of the government Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction.

The Rolleston Report framed addiction as an illness and established a framework that placed primary responsibility for it with the medical profession. It allowed doctors to prescribe maintenance doses of drugs to those for whom withdrawal wasn’t feasible.

“Many psychiatrists had the view that the only treatment was to get people off drugs completely,” Dr. John Marks told Filter. Marks is a former psychiatrist who bucked that trend.

But after the adoption of the 1961 UN Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs, which set out the principles of global prohibition, Britain introduced regulations in 1971 that meant only psychiatrists could prescribe heroin at specialist clinics. This effectively ended the so-called “British system.”

“Many psychiatrists had the view that the only treatment was to get people off drugs completely,” Dr. John Marks told Filter.

Marks is a former psychiatrist who bucked that trend. He is renowned for running maintenance clinics in North West England for 13 years in the 1980s and ‘90s, in what became known as the “Merseyside experiment.”

When Marks began working as a consultant psychiatrist in Widnes, a small town near Liverpool, and was asked to take charge of an existing Rolleston-style clinic, he initially shared the view of many of his colleagues.

“It seemed so pointless to me, I wanted to try something different,” he said. “But I was told to leave it alone, that it ‘just works.’”

As time went on and he got to know the patients, his perspective began to shift.

Mortality fell sharply in Widnes, reflecting people’s access to drugs of known dosage without adulterants.

“There was one patient, Sid, a reasonably smart, working-class ex-docker, with a wife and kids. There was nothing to distinguish him from you or me,” he said. “[Sid] was the opposite of what the public thinks of as an ‘addict,’ and that made me look into this further.”

With research funding from the government, Marks and his colleague, Dr. Russell Newcombe, began investigating the effects of the Widnes Drug Dependency Clinic, monitoring patients and comparing outcomes to those in Bootle, a nearby town where only abstinence-based treatment was offered.

Mortality fell sharply in Widnes compared to areas where heroin was not prescribed, reflecting people’s access to drugs of known dosage without adulterants. That’s in line with what we know about modern safe supply programs.

“In Bootle, there was a 16 percent mortality rate,” Marks said of that cohort. “In Widnes, we didn’t have a single death.”

But more surprising, Marks said, was the impact on rates of drug dependency. “There was a decrease in incidences of addiction from 207.6 per 100,000 to 15.83. That is an 18-fold, over 90-percent reduction.”

Marks was then invited to set up a similar clinic in Liverpool, which was “as successful, on a much larger scale.”

In addition, when people could obtain drugs legally—and without having to find the means to pay for them, due to the United Kingdom’s universal health care system—they were far less likely to be arrested.

“In the comparison group, there were 6.88 criminal convictions per patient per year,” Marks said. “In Widnes, it was 0.44. That’s a 12-fold reduction.”

Marks was then invited to set up a similar clinic in Liverpool, which was “as successful, on a much larger scale.” So much so that in 1990, the retail chain Marks & Spencer sponsored the world’s first international conference on harm reduction in the city, after seeing a dramatic fall in shoplifting at its local stores.

After his research was published in 1991, journalists began contacting Marks, and he gave numerous media interviews about his work, which was often portrayed as “controversial.”

As Toby Seddon wrote in a 2020 paper about Marks and the Merseyside model, his supporters saw him as a “humane doctor responding pragmatically to an extraordinary social problem,” but to his critics, he was an “irresponsible maverick who risked prolonging addiction careers and expanding the heroin-using population.”

As US influence drove international pressure, the British clinics were closed down in 1995. Marks became “vilified” and left the UK.

A number of senior politicians at the time, including the Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and Health Minister Norman Fowler, were supportive of Marks. But political pressure was mounting—including from the United States, where President Richard Nixon’s “War on Drugs,” enthusiastically escalated by his successors, had ramped up enforcement of prohibition.

“It was two opposing political ideologies,” Neil Woods told Filter. A former police officer-turned advocate with LEAP (Law Enforcement Action Partnership), he’s now a prominent British opponent of the drug war he once fought.

“The British system viewed someone with a problem as having an unfortunate medical condition and offered them help,” he said. “The American system saw addiction as a moral failing [for] which people should be criminalized. But after the Second World War, we owed America enormous amounts of money.”

As US influence drove international pressure to establish coordinated global prohibition, the British clinics were closed down in 1995. Marks became “vilified,” as he put it, and left the UK for New Zealand, eventually leaving the field of addiction medicine too.

Yet the Merseyside experiment would be used to inform similar drug policies and regulation pilots around the world, such as Switzerland’s prescribed heroin program, which launched in 1994.

An evaluation of its results found large reductions in illicit drug use and drug-related convictions and significant improvement in participants’ health and social status. No overdose-related deaths were recorded.

Implementing programs like the Merseyside model once again would not necessarily require a major change in legislation.

“Almost all of those in the initial cohorts [of the program] are no longer using heroin,” Woods noted. “As soon as you medically control it, the market shrinks. In Switzerland, there are no children dealing heroin.”

Meanwhile, in England, the Children’s Society estimates that 46,000 children are being exploited by ‘“County Lines” gangs. Over 300,000 adults were registered with drug and alcohol treatment services in 2024, and drug-related deaths are at a 30-year high.

“There are many reasons why [current drug laws] are not working,” Woods said. “Not least of which is that criminalizing people stigmatizes them and makes it harder to get help.”

But implementing programs like the Merseyside model once again would not necessarily require a major change in legislation.

In 2019, a heroin-assisted treatment pilot was launched in Middlesbrough, with a licence to prescribe patients a supervised dose of diamorphine twice a day.

An assessment by the University of Teesside found that the majority of those who took part in the first year reported improvements in wellbeing and quality of life, with none reporting any new injection-related wounds or infections. Most either stopped or reduced their use of unregulated heroin, and there was a reported 60-percent reduction in criminalized behaviors. There were no deaths among participants over the 12-month period.

But the program was forced to close in 2022, after its funding was cut.

Marks is saddened by the current state of British drug policy, and the sense that even if the country is able to move forward once again, it wasted decades by banning a model that “just works.”

The UK government continues to insist it will not revisit laws to allow for overdose prevention centers—though Scotland opened its first in 2025, authorized and funded by the Scottish government—despite recent pressure from the UK Parliament’s Scottish Affairs Committee.

At the Scottish Green Party’s annual conference in October, members voted overwhelmingly to approve a policy calling for the regulation of drugs in Scotland.

MSP Maggie Chapman

Maggie Chapman, a member of the Scottish Parliament and the Scottish Greens’ spokesperson on drugs, said the country’s “appalling drug death numbers” show the drug war has “obviously” failed. Her party now calls for a “compassionate” and “evidence-led” approach, with all drugs—including alcohol and nicotine—regulated according to risks, alongside a clear prevention strategy.

“It has to sit alongside a preventative approach,” Chapman told Filter. “That includes investing in care and support services that aren’t about punishment or fixing the problem once it’s happened.”

The Greens believe their policy strikes the right balance between strict prohibition and an unrestrained commercial market.

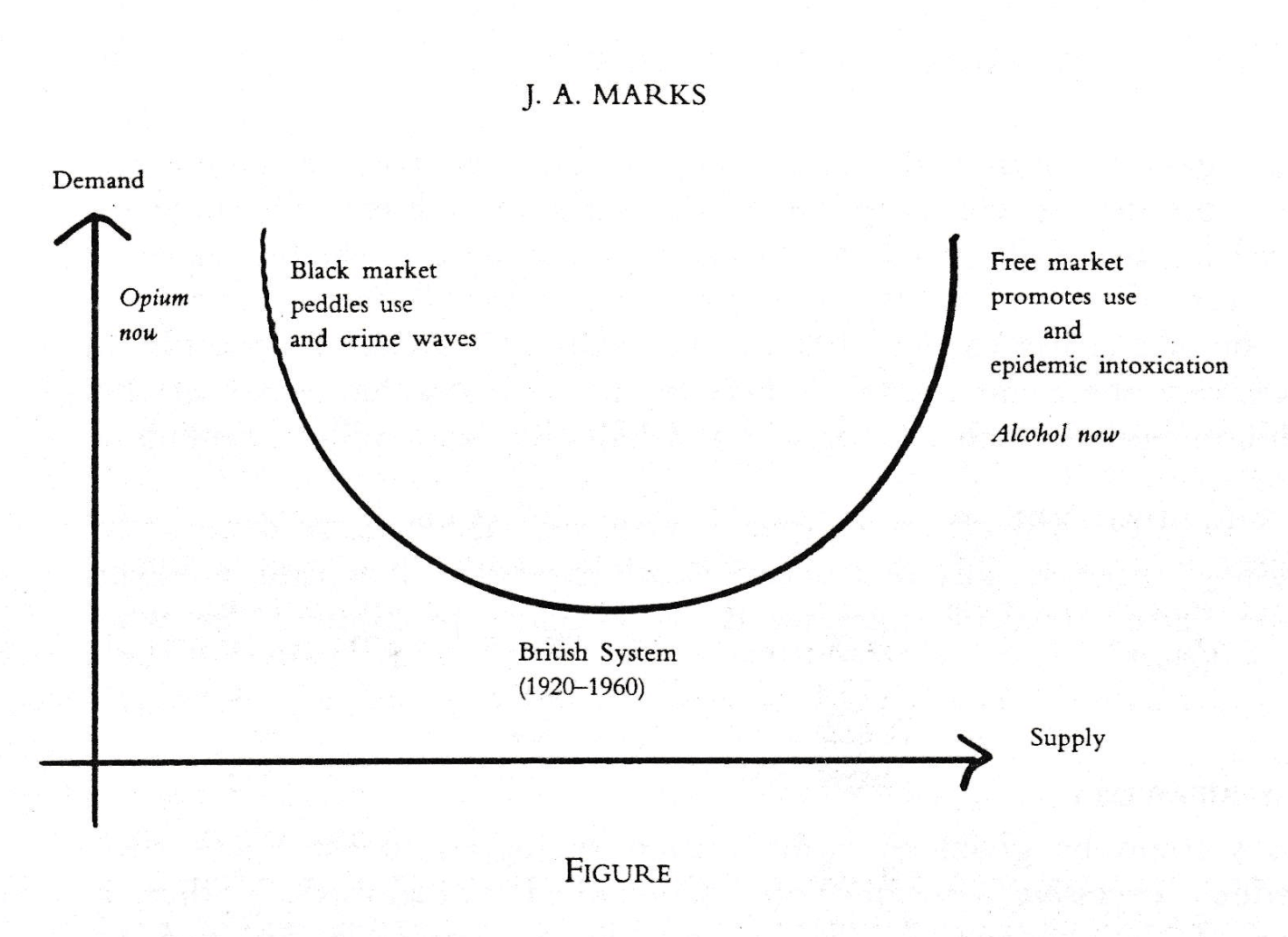

This supposed sweet spot of regulated control is illustrated by a bell curve in Marks’ seminal 1991 paper, titled, “The North Wind and the Sun.”

“Free markets promote consumption, black markets peddle consumption, regulated markets control consumption,” Marks said.

He’s saddened by the current state of British drug policy, and the sense that even if the country is able to move forward once again, it wasted decades by banning a model that “just works.”

Top photograph (adapted) via PublicDomainPictures. Photograph of Maggie Chapman by Sarah Sinclair. Graphic courtesy of Dr. John Marks.

LEAP was formerly the fiscal sponsor of The Influence Foundation, which operates Filter. Filter‘s Editorial Independence Policy applies.