In recent years, Nobel Prize–winning physicist James Peebles, one of the main architects of the standard cosmological model, has pointed out several mysteries challenging our understanding of the cosmos. While the well-known Hubble tension often takes the spotlight, a lesser-known issue — the cosmic dipole anomaly — might be even more fundamental.

Late in December 2025, Indian-born astrophysicist and cosmologist Subir Sarkar, a colleague of the late Jayant Narlikar, published an article in The Conversation. In it, he presented one of cosmology’s most puzzling anomalies, questioning the reliability of the standard model — much like the tension between two different measurements of the Hubble constant.

This isn’t an anomaly that disputes the existence of dark matter or dark energy, but rather a subtle disagreement between predictions made before those two elements were added to the Lambda-CDM model and the vast astronomical data we’ve since gathered.

The discrepancy was first reported by Sarkar and his team in 2022 in a paper on arXiv, later expanded and published in Reviews of Modern Physics.

It stems from data collected over recent decades — millions of distant radio sources observed by the NRAO VLA Sky Survey (NVSS) and numerous quasars captured by NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Explorer (WISE).

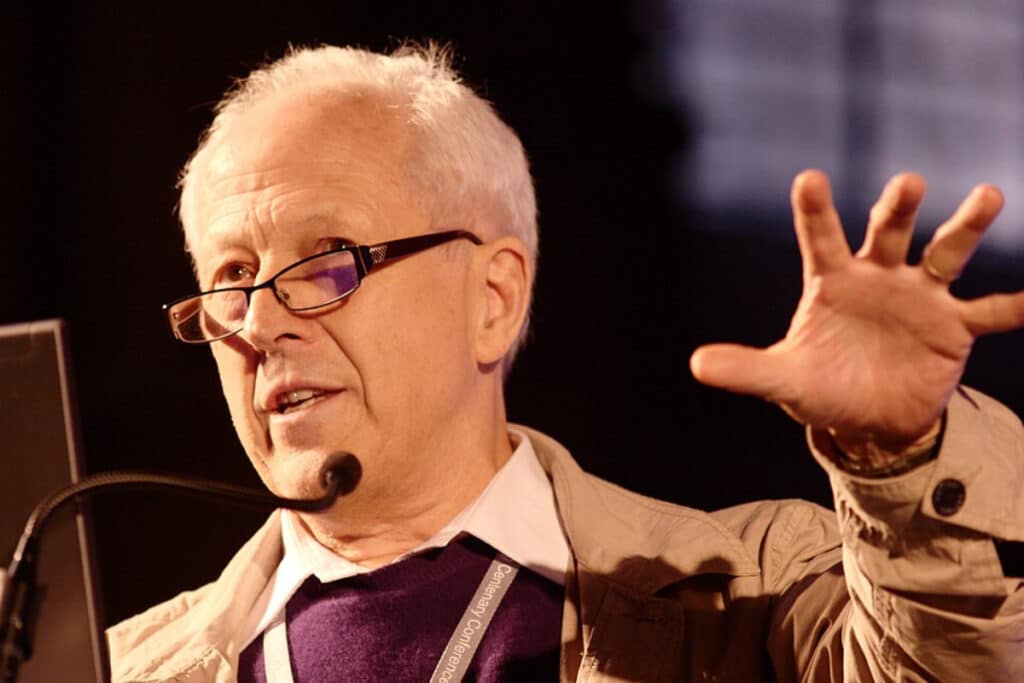

These observations allowed scientists to apply a test proposed back in 1984 by cosmologist George Ellis (known for coauthoring The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time with Stephen Hawking) and astrophysicist John Baldwin — a test now famously called the Ellis–Baldwin test.

South African cosmologist George Ellis. © David Monniaux, CC by-sa 3.0

A century of relativistic cosmology

To grasp the significance of this finding, we need to rewind to 1917, when Albert Einstein first applied his theory of general relativity to the Universe as a whole. His ideas were groundbreaking — but risky.

At that time, scientists were still debating whether the nebulae visible in the sky were other galaxies or part of our own Milky Way. Einstein assumed they were indeed separate galaxies, evenly distributed throughout space (a property called homogeneity). He also believed the Milky Way had no special place in the cosmos, meaning the Universe should look the same in every direction — isotropic as well as homogeneous.

He introduced the famous cosmological constant, now understood as a form of dark energy, to maintain a static Universe.

But soon after, Friedmann and Lemaître proposed new solutions to Einstein’s equations. They suggested a dynamic Universe — one that could expand or contract — with different possible geometries and even different topologies.

How the Big Bang theory was discovered: Einstein, Lemaître, the cosmic microwave background. Documentary excerpt from the magazine Cassiopée, episode 4 “The Big Bang”. © Jean-Pierre Lu minet, France Supervision (1995)

A homogeneous and isotropic cosmos?

By the 1930s, mathematicians Howard Robertson and Arthur Walker developed what we now call the FLRW metric — the general model describing a Universe that is homogeneous and isotropic. It could be curved like a sphere, flat like an infinite plane (or torus), or curved negatively like a saddle.

However, there’s no guarantee the Universe is truly that uniform everywhere, or that it always was in the past. These assumptions simply make Einstein’s equations easier to solve and predict. Fortunately, we can test them with precise observations.

The cosmic microwave background — the faint glow left from the Big Bang — shows that 13.7 billion years ago, about 380,000 years after the beginning, the Universe was remarkably smooth. Temperature variations across the sky are tiny, meaning matter was evenly spread. Observations of distant quasars also support this, albeit with less precision.

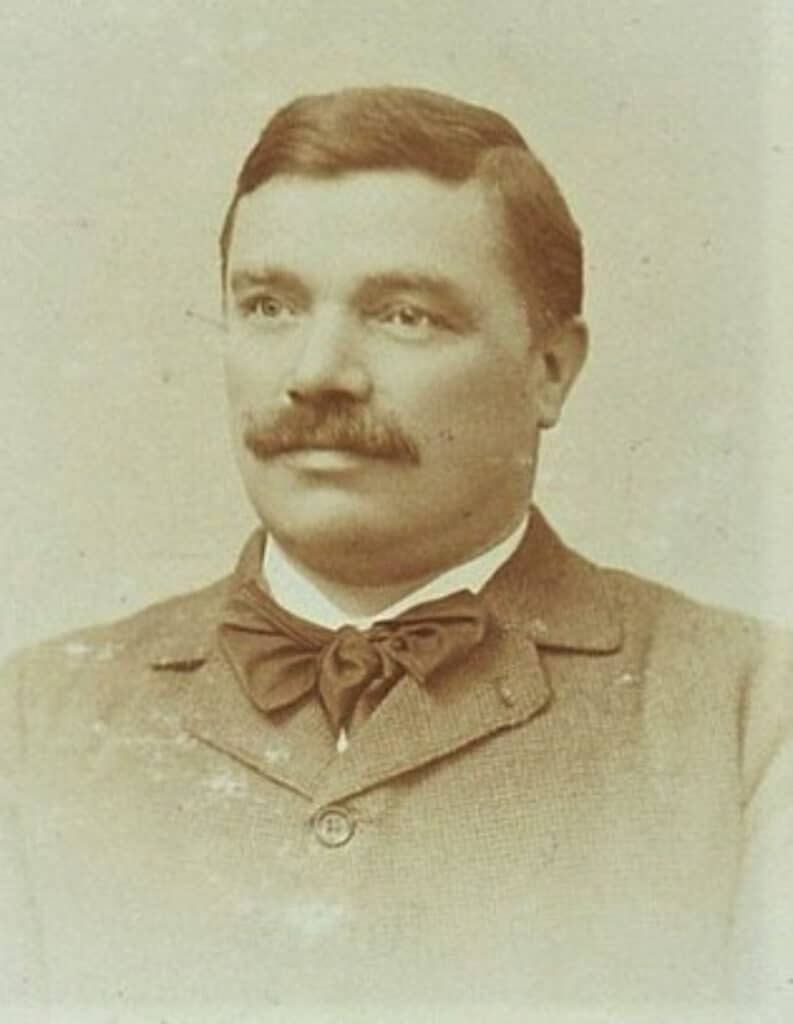

The Italian mathematician Luigi Bianchi (1856–1928). © DP

A zoo of cosmological models

Of course, reality might be more complicated.

At the turn of the 20th century, Italian mathematicians were exploring the geometry of curved spaces, and Luigi Bianchi discovered that in three dimensions, several homogeneous but anisotropic models — ones not uniform in every direction — could exist. Later, American mathematician Luther Pfahler Eisenhart expanded this classification, showing there were more possible cosmological models than previously thought.

After World War II, and especially after the discovery of the cosmic background radiation, these models were studied intensively. In fact, most advanced relativity courses — like Landau’s — still cover them today.

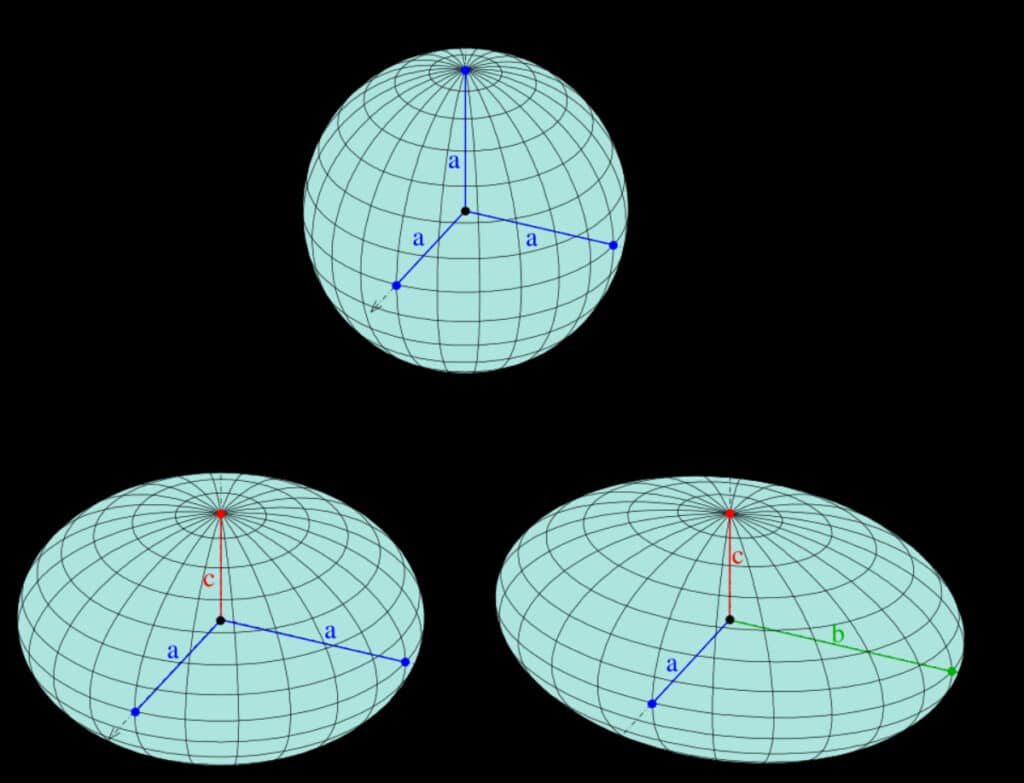

Bianchi’s theory, based on the symmetries of space, ties into group theory, notably that of Sophus Lie. But you don’t need to dive into the maths to understand what Sarkar’s research implies — it can be pictured simply.

The Bianchi classification of spaces, used in relativistic cosmology to classify various homogeneous but anisotropic models, is very similar to that of the ellipsoids in this diagram, whose symmetries vary depending on the lengths of their axes. © Ag2gaeh, CC by-sa 4.0

Imagine a sphere that looks the same from every direction. Now picture an ellipsoid — stretched along one axis — that looks different depending on how you view it. That’s what an anisotropic Universe would be like. In some models, these distortions change over time, sometimes chaotically, as in a Kasner Universe.

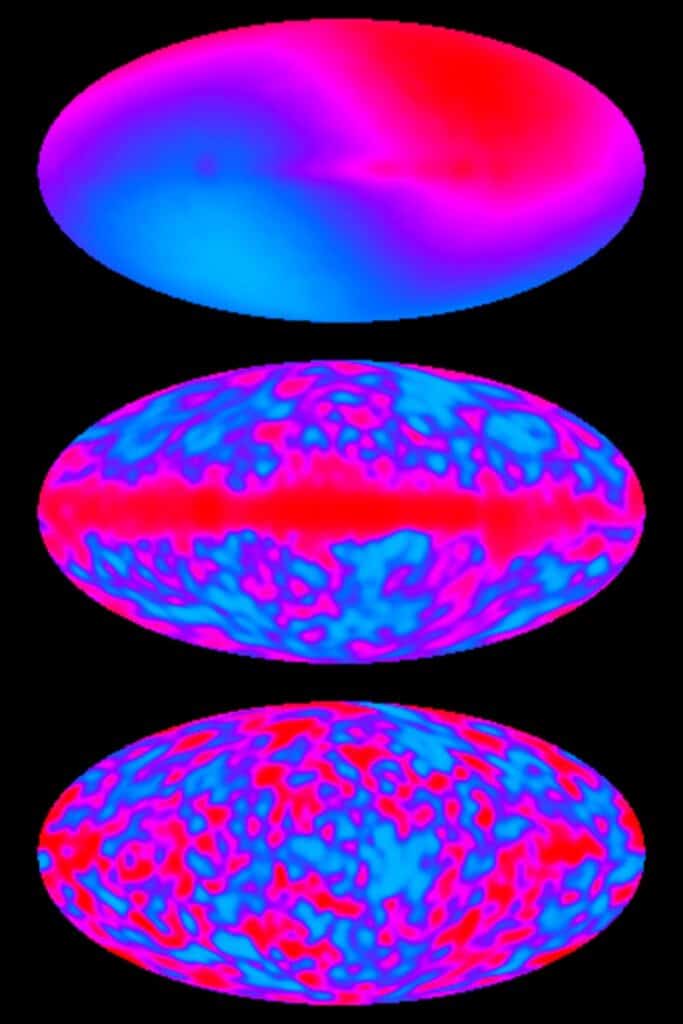

Other models begin with anisotropic expansion early on but gradually evolve toward isotropy. Such models affect how we perceive the cosmic background radiation, influencing the temperature map captured by missions like COBE in the 1990s and later refined by WMAP and Planck, which set tight limits on how much anisotropy our Universe could have.

This series of false-color images was created from two years of observations of the cosmic microwave background radiation by the CoBE satellite. The colors indicate temperature variations, with the hottest areas in red and the coolest at the bottom. From top to bottom, we see the map including the cosmic dipole, then the contribution of galactic radiation in the center, and finally, at the bottom, the map without these two contributions to the microwave background radiation. The dipole, a gradual variation between relatively hot and relatively cool areas, from the upper right to the lower left corner, is due to the motion of the Solar System relative to the distant matter of the Universe. The signals attributed to this variation are extremely weak, a thousand times less bright than the sky. The following image therefore shows only the reduced map (i.e., without the dipole or galactic emission). Fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background are extremely small, on the order of 1/100,000 compared to the average temperature of 2.73 kelvins of the radiation field. This radiation is a remnant of the Big Bang; its fluctuations reflect the density contrasts in the early Universe. These density ripples are thought to be the origin of the structures that populate the Universe today: clusters of galaxies and vast regions devoid of galaxies. © NASA

The cosmic dipole anomaly

Now we can return to the so-called cosmic dipole anomaly, first spotted in data from the COBE satellite and later confirmed by Planck with greater precision.

These satellites measured microwave background radiation across the sky. Most of this light dates back 380,000 years after the Big Bang, but some contamination — like dust from our own galaxy — had to be removed. Cosmologist Laurence Perotto helped clarify these foreground effects, which scientists subtracted to reveal the true signal.

Because the Milky Way moves relative to the background radiation, scientists expected a Doppler effect — a shift in temperature appearing as red and blue regions in opposite directions. This pattern, called the dipole, reflects our galaxy’s motion through space at about 370 km/s.

In 1984, Ellis and Baldwin predicted that once astronomers could map enough radio sources and quasars, they would detect a similar dipole pattern there too. And if that dipole didn’t align with the one in the cosmic background, it would suggest a violation of the Cosmological Principle — meaning the Universe might not be as uniform as we thought.

That’s exactly what Sarkar and his team believe they’ve found: a significant mismatch in over a million radio sources and half a million quasars. The signal, reaching five sigma in significance, suggests it’s not a random fluctuation — like seeing a face in the clouds when none is really there.

Still, caution is necessary. As Sarkar wrote in The Conversation:

“An avalanche of data is expected from new satellites like Euclid and SPHEREx, and telescopes such as the Vera Rubin Observatory and the Square Kilometre Array. It’s possible we’ll soon gain unprecedented insight into how to build a new cosmological model, using advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning.”

If that happens, the impact on physics — and our understanding of the Universe itself — could be truly profound.

APC Symposium, June 26, 2023. Speaker: Roya Mohayaee. The origin of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) dipole is attributed to the anisotropic distribution of matter in the local Universe. If the Universe is statistically homogeneous and isotropic on large scales, as proposed by the cosmological principle, then the CMB dipole and the dipole of high-redshifted matter should coincide. Based on a recent sample of quasars from the WISE survey, the CMB’s proper frame of reference and that of matter do not overlap; therefore, the cosmological principle is violated. © Astroparticle & Cosmology Laboratory (APC)

Laurent Sacco

Journalist

Born in Vichy in 1969, I grew up during the Apollo era, inspired by space exploration, nuclear energy, and major scientific discoveries. Early on, I developed a passion for quantum physics, relativity, and epistemology, influenced by thinkers like Russell, Popper, and Teilhard de Chardin, as well as scientists such as Paul Davies and Haroun Tazieff.

I studied particle physics at Blaise-Pascal University in Clermont-Ferrand, with a parallel interest in geosciences and paleontology, where I later worked on fossil reconstructions. Curious and multidisciplinary, I joined Futura to write about quantum theory, black holes, cosmology, and astrophysics, while continuing to explore topics like exobiology, volcanology, mathematics, and energy issues.

I’ve interviewed renowned scientists such as Françoise Combes, Abhay Ashtekar, and Aurélien Barrau, and completed advanced courses in astrophysics at the Paris and Côte d’Azur Observatories. Since 2024, I’ve served on the scientific committee of the Cosmos prize. I also remain deeply connected to the Russian and Ukrainian scientific traditions, which shaped my early academic learning.