“This government has been bold. I’d give it 10 out of 10 for everything it has said and everything it’s trying to do, but the proof is in the pudding,” says Skanska UK CEO Katy Dowding.

Katy Dowding is president and CEO, Skanska UK

Having taken up her current role in April 2023 following a 22-year history with Skanska across various leadership positions, Dowding has had a ringside view of major UK schemes including HS2 under the Skanska Costain Strabag (SCS) joint venture – and Lower Thames Crossing as a key delivery partner.

She indicates that her experience across these key projects, alongside a host of other critical schemes, has demonstrated that the “proof in the pudding” – in other words delivery success or otherwise – is a question of clarity, communication and continuity.

And she believes the government’s 10-Year Infrastructure Strategy, launched in mid-2025, “is a good piece of work” that will help here.

“It starts from a mindset that you can’t think of infrastructure in four-or-five-year political cycles; four or five years isn’t enough to achieve anything,” she says. That’s why the formation of Nista [the National Infrastructure and Service Transformation Authority] is critical.”

Also welcome is extra investment in planning encapsulated in The Planning and Infrastructure Bill, “but it’s going to take a while and it just needs to keep the momentum,” she says. “People need to be able to hold their nerve.”

Holding their nerve requires bringing certainty to an uncertain world in which fluctuating costs and geopolitical factors loom increasingly large, by getting clear on objectives.

“Typically, what we’ve seen is government trying to please too many audiences, because large scale strategic infrastructure is expensive and you have to make decisions to turn some things off if you’re going to proceed with others. Plans can get derailed if we get into another set of elections and they’re trying to keep so many different factions happy that they end up pleasing nobody.”

The current state of the water sector does beg the question as to whether the whole sector needs a bit of an overhaul. This will probably be the last AMP under the current guise, so it feels ripe for a fresh look

Construction productivity

As a member of the Construction Productivity Taskforce, Dowding is keen to get clarity on the issues at the heart of the construction sector’s productivity woes.

“Productivity problems don’t tend to be when somebody’s laying a brick or putting a bit of tarmac down. The real productivity problem we have is around what blocks us from doing construction and what we can do in terms of getting it underway.”

Planning is one example of those blockers, she says, citing what she sees as the positive work government is currently doing around limiting the number of the objections to projects.

“In a democracy, people should absolutely be able to say if they’re not happy, but it needs to be proportionate.” The £100M Sheephouse Wood Bat Protection Structure or “bat tunnel” to safeguard rare bats from the HS2 rail line, was a case in point. “Nobody’s saying we shouldn’t be looking after bats, but the response needs to be proportionate.”

At the same time, Dowding stresses that planning and dealing with objections are only part of the picture. “The work we’ve been doing on the Productivity Taskforce includes looking at the pipeline from policy to delivery, because it’s no one thing that stifles productivity.”

One area ripe for reassessment is project selection. Hasty selection of infrastructure projects forces decisions before sufficient detail is known, potentially leading to cost overruns, delays, mission creep and lack of alignment with needs.

“For me, it’s about connecting the pipeline to outcomes. If the government decides ‘we’re going to build this road or that railway’, the pipeline can almost become a wish list, and of course, a wish list is always going to be unaffordable.

“I think we need to start with the government’s missions or stated strategic objectives and then look at how do they flow through into what’s in the pipeline? If there are jobs on the pipeline that are just a wish list, which aren’t connected through to the mission, they should be deselected.”

She is also pushing for earlier engagement and collaboration, while noting that approaches like Project 13 remain relatively limited in uptake. “Project 13 is great, but it’s not happening everywhere. There’s still a lot of traditional procurement being done by the public sector. I don’t think it specifically needs to be Project 13, but we need more of a culture of collaborative contracting.

“If you look at the private sector, we pretty much wholesale – with very few exceptions – use collaborative procurement models. Now, there’s no way the private sector would be doing that if it didn’t give them value for money, if it wasn’t efficient, if there wasn’t the value to be derived from that. And in that scenario, what you normally get is deselection at a much earlier stage, so you don’t run in competition with each other.

“Typically, on a private sector job, there might be anything between four and six of us tendering, but you just do a first stage tender where you work on programme capability, markup and those kinds of things. Then you might spend a year working together, working up the design together to make sure you’ve got buildability, making value engineering choices. You might add something in because you can make the case that the value it brings is greater than the cost. On the other hand, you might say – we don’t need these other elements at all.

“By contrast, if you’re in a competitive model for a long time, it’s very hard to look at different options. Instead, you say, this is the design and you’ve all got to price the design like that – so you end up with unrealistic pricing.”

TBM Sushila removed after completing an 8km journey to construct HS2’s Northolt Tunnel under the capital

Grasping value

The perception of unrealistic pricing has arguably been a defining factor in HS2’s controversies. When former prime minister Rishi Sunak announced the cancellation of the northern leg of HS2 in October 2023, Dowding quips, “I’ll probably have better days at the office, but the big challenge with that is – and we’re partly to blame for this – we don’t talk enough about the value projects deliver or why we’re doing a project, because we seem to get obsessed with cost.

“Clearly cost is important and nobody wants to throw money out the window, but it’s communicating the real value of a project – based on a clear understanding of its objectives – that’s critical.

“The example I always use is The Olympics. Of course we talked about the cost of the Olympics, but everybody got why we were doing it. Everybody got why we had to get it finished in time for summer 2012. There was a hard stop there. The public got it. The trades on site got it.”

Of HS2, she acknowledges: “There was definitely a lot more work to be done upfront before we started on site” and she adds that this extends to questioning whether speed should have been the scheme’s main driver.

“It was capacity-building, and that’s about understanding, okay, why is it important? Well, capacity-building means passenger trains will be able to travel faster. Freight will be able to get around the country better. All of that got lost within the narrative that came through about it being seven minutes quicker to get to Birmingham.”

She sees Lower Thames Crossing – which secured final government funding late last year – as an opportunity to do things differently.

“With LTC, we’ve been working with the customer for a lot longer and more closely, so there’s been some good collaboration there, and National Highways is committed to doing the right thing.

“LTC is particularly about carbon as a pathfinder project, and everybody knew that at the outset. [LTC executive director] Matt Palmer stood up and said, this is going to be the greenest road in the UK. So that takes us back to that point about the Olympics; everyone knows we’re going to have the best games in 2012. Everyone knows we’re going to have the greenest road. We know where we’re going.”

Following COP30 in late 2025, where it was made clear that climate change mitigation is under threat, Dowding also sees LTC as one pathway in returning carbon reduction to centre stage.

“It feels like there’s been a de-emphasis from the government. So for us, it’s important to get clear on where that’s going because we are very driven by being able to reduce carbon to provide greener solutions. It’s been motivating for Skanska and I see it as a differentiator for us, so if that’s being valued less by clients, that’s a shame.”

Skanska deployed the world’s first hydrogen-fuelled excavator on site for LTC ground investigation surveys, aligned with the project’s aims to eliminate diesel from worksites entirely by 2027. It is also focusing on the use of low carbon concrete and steel, as well as trialling innovative materials such as calcined London clay as a cement replacement, and recycled steel fibres.

But overall, a clear vision and embedded efficiencies also have a role to play.

“Carbon and cost are often seen as in competition with each other, which they don’t need to be at all,” says Dowding. “If you can secure site efficiencies, project efficiencies and deliver a project more quickly, you will be delivering it, obviously, with less embodied carbon.”

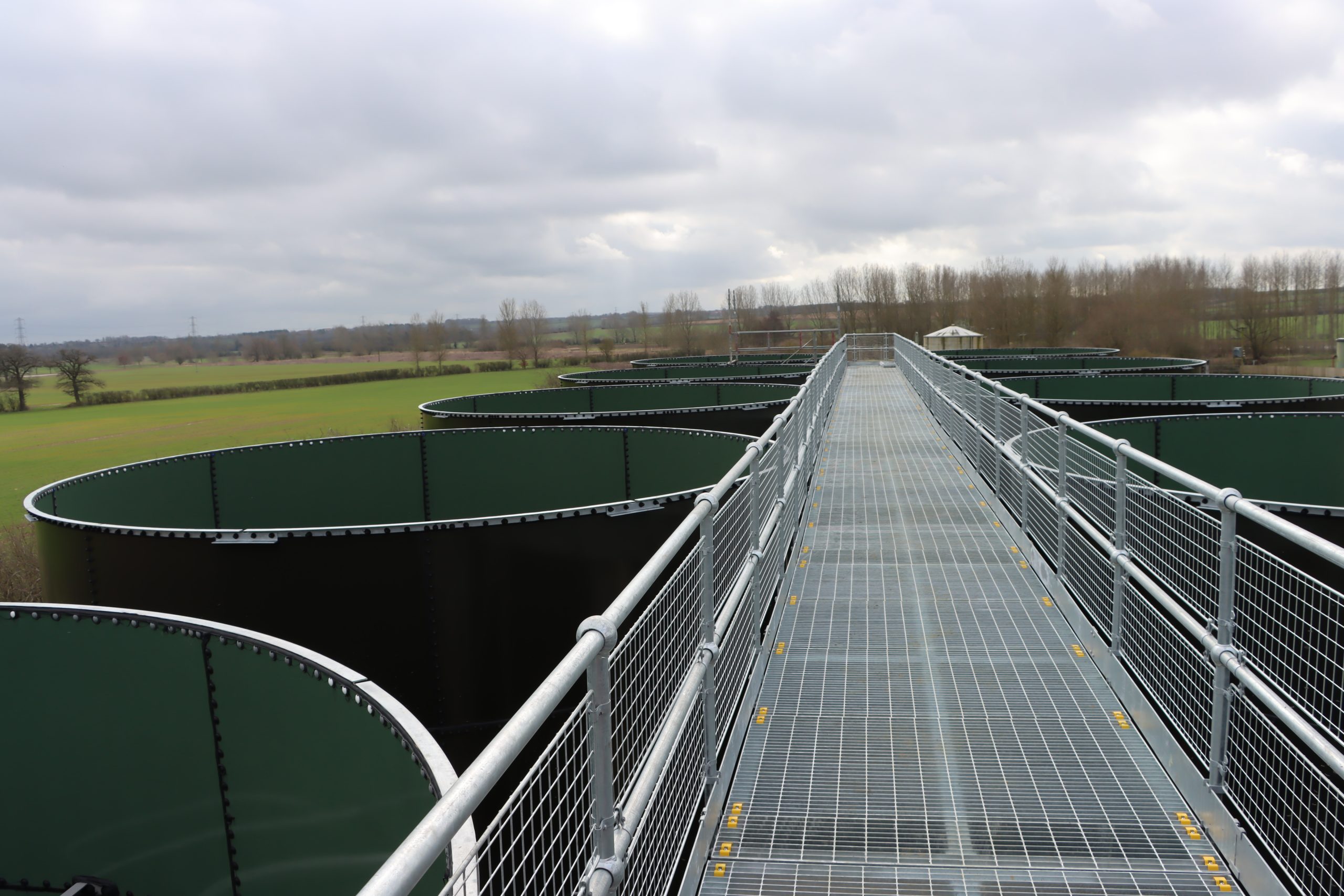

Skanska has been a member in Anglian Water’s @One Alliance since 2005

2026 and beyond

Infrastructure in the UK is undergoing a seismic shift that will see Skanska UK broadening its portfolio, Dowding says.

“There’s some exciting stuff going on in the energy sector in terms of transmission and substations for National Grid’s Great Grid Upgrade,” she says. “There are a number of National Grid projects in procurement at the moment. We’re looking at certain ones within the National Grid portfolio.”

Meanwhile in the water sector, Skanska has worked with Anglian Water for about 25 years and became part of @one Alliance in 2005. The organisation keeps a weather eye on opportunities to contribute to the sector, although she notes: “It’s very disjointed regional procurement for water. Every region’s got a different commercial model. It’s quite tricky to find the ones that work, and they come up with different ways of doing it. So, it’s inconsistent.

“The current state of the water sector does beg the question as to whether the whole sector needs a bit of an overhaul. This will probably be the last AMP under the current guise, so it feels ripe for a fresh look.”

Continuity factor

More widely, continuing to strengthen relationships and engagement is critical, and industry – including Tier 1 contractors – has a role to play.

“This is where we need to work more closely with government, because central government aren’t construction experts but we’re not expert politicians. We need to bring the two parts together so we can craft that story to make sense of that.

“If we can get government to continue to engage with industry, we can help them work out priorities, which helps us work out – working with Nista – industry’s priorities.

“I think we’re also starting to see both the political arm of government and the civil service working more closely with industry. Part of the secret is the civil service, because that provides the continuity factor.

“We’ve now got a government manifesto, which has its missions and strategic objectives, and if you’ve got that connection from manifesto to policy, through to pipeline, through to delivery – if that thread is there, it should be the catalyst for better inter-departmental collaboration.

“Beyond that, if we can get that long-term thinking, my nirvana would be cross-party support for a 10-year plus infrastructure plan. Wouldn’t that be amazing? And then they could agree, ‘Look, this is going to happen no matter who’s in or who’s out’.”

Like what you’ve read? To receive New Civil Engineer’s daily and weekly newsletters click here.