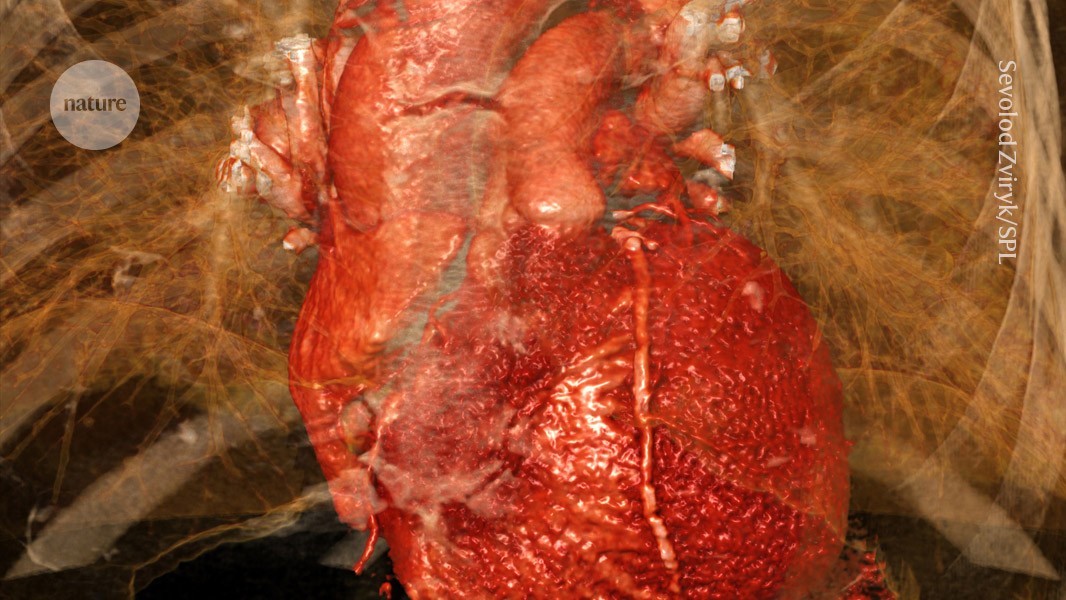

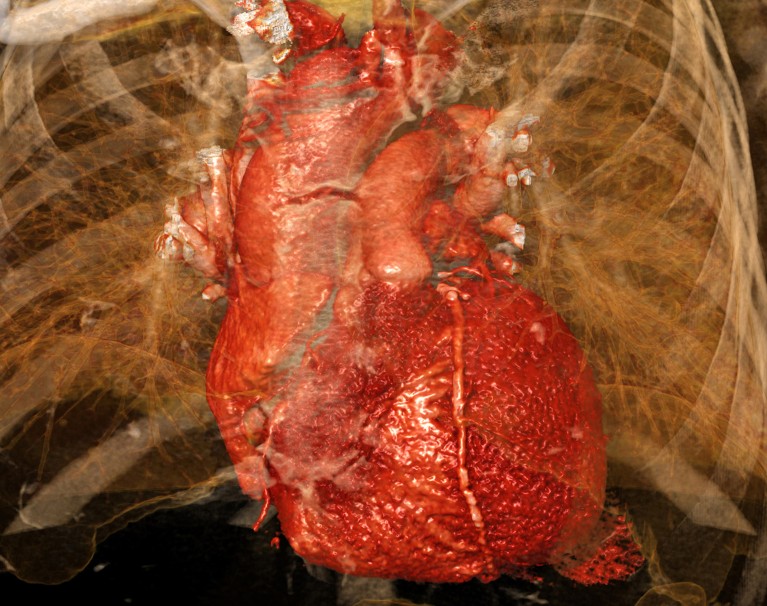

Heart damage caused by a myocardial infarction is exacerbated by activation of a heart–brain–immune axis.Credit: Sevolod Zviryk/Science Photo Library

Researchers have proposed a rethink of the brain’s role in heart attacks, finding that crosstalk between the heart, the brain and the immune system damages the heart after a myocardial infarction in mice. The results, published in Cell on 27 January1, suggest that such events are not just diseases of the cardiovascular system.

In the study, scientists identify a brain–immune circuit that exacerbates cardiovascular pathology during a heart attack. They identified neurons in the vagus nerve that relay signals between the heart and the brain, which in turn activates immune and inflammatory responses and causes widespread damage to the heart. Blocking this pathway improved outcomes after a heart attack in mice, which could pave the way for developing new therapies.

“The heart does not exist in isolation. The nervous system talks to the heart, the immune system talks to the heart,“ says study co-author Vineet Augustine, a neuroscientist at the University of California, San Diego. The current work is a “step forward into putting all of these systems together and this approach can be applied to other diseases as well”, he adds.

“We have known for decades that the brain and nervous systems are critical components to [heart attack] pathogenesis, management and care,” says Cameron McAlpine who studies immune function in the cardiovascular and nervous systems at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City. “It appears that this axis plays a critical role.“

Brain–heart axis

Heart attacks happen when blood flow to the heart muscle is blocked. They cause damage to the heart’s muscles, and trigger cellular and molecular changes across its tissues.

“The heart attack is exactly like an earthquake. You have an epicentre, which is a focal point and then it spreads out,” explains Augustine. “Once it starts spreading out, this is when a large chunk of the tissue dies.”

Earlier research has shown that the vagus nerve — a key pathway that connects the brain to many other organs — sends signals to the brain after a heart attack.

“All the regular functions of the heart are controlled by the nervous system,” says Kalyanam Shivkumar, a cardiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles.

These post-heart attack signals from the heart to the brain result trigger the sympathetic nervous system — the body’s ‘fight or flight’ response — he explains. The increased sympathetic response then causes inflammation in the heart tissues and impairs cardiac function, which can lead to heart failure.

“The root cause of the problem is signals going from the heart to the brain,” says Shivkumar. But the key cells and molecular pathways that underlie these processes have remained unclear.

Found: the dial in the brain that controls the immune system

To investigate this, Augustine and his colleagues experimentally induced heart attacks in mice by permanently blocking an artery in their hearts.

First, they aimed to trace how nerve connections between the heart and the vagus nerve change after a heart attack. They found that a group of sensory neurons in the vagus nerve that detect harmful stimuli grew new projections around the injured part of the heart.

Blocking these neurons reduced the damage and inflammation in the heart’s tissues and stabilized its rate and rhythm. “Those neurons directly talk to the area of the heart where the injury is,” says Augustine. By silencing them, “you can really quickly prevent it from expanding. And so the injury becomes extremely, extremely small”.