It was believed to be a source of sacred power.

Rebecca McGrath

06:30, 29 Jan 2026Updated 06:50, 29 Jan 2026

Monk’s Well in Wavertree.(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

On a Liverpool street is a mysterious medieval relic hiding in plain sight. Just a stone throw away from a children’s park and Picton Clock in Wavertree, Monk’s Well, a Grade II listed holy well, can be found standing outside two semi-detached houses on the corner of North Drive and Mill Lane.

The well was constructed in the early 15th century in 1414 and is believed to have been used by medieval monks and travellers. Despite being centuries old, the site is still surrounded in mystery, remaining a place of local folklore and unanswered questions.

Professor Martin Heale, professor of late medieval and reformation history at the University of Liverpool, told the ECHO that although holy wells were not uncommon in medieval Britain and Ireland, the usage of the well still remains uncertain.

A medieval holy well was believed to be a source of sacred power.(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

He said: “Holy wells were not uncommon in medieval Britain and Ireland. They were places where you might go on pilgrimage for healing or hope, in an age when doctors were expensive and often ineffective.

“We do not know whether the Wavertree well was ever a major place of pilgrimage: the most popular sites were accompanied by well-chapels, as at Holywell in Flintshire, whereas the Wavertree well seems only to have been surmounted by the medieval sandstone arch which survives.

“A medieval holy well was believed to be a source of sacred power, albeit with highly practical purposes like healing.

“After the protestant reformation of the sixteenth century, which dismissed holy sites and relics as superstitious, sacred wells were sometimes revived as spas with medicinal properties.”

The well was built from sandstone and originally had steps leading down to the spring and was topped with a holy cross.

The well was constructed in the early 15th century.(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

Professor Martin Heale added: “We actually know very little about the changing fortunes and usage of the well over the centuries. The stone arch is apparently medieval, but the inscription which gives the date 1414 is in more modern lettering.

“The fact that the monument survived largely intact down to the 1800s suggests some continued use after the 1500s, perhaps as a spa, or as a site which appealed to those with Catholic sympathies like Holywell. By the nineteenth century, the well had acquired a kind of heritage or antiquarian value and so was considered worth preserving.

“The Wavertree well provides a rare link to the origins of Liverpool as a medieval town and port, with its royal charter of 1207 and thirteenth-century castle.

“We have no concrete evidence linking the well to monks. Wavertree manor was never in the hands of a monastery, and there was no medieval abbey or priory nearby.

“The connection with monks may well be a later tradition, therefore. Medieval holy wells were sometimes overseen by a monastery, but by no means always.

It is a Grade II listed holy well.(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

“Almost all traces of medieval Liverpool have been lost, overwritten by the spectacular development of the city in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The well reminds us that Liverpool has a long and varied history.

“There are a fair number of locations around Britain which have been thought, at one time or another, to have served as sacred wells. But relatively few wells with standing medieval masonry survive, as at Wavertree.

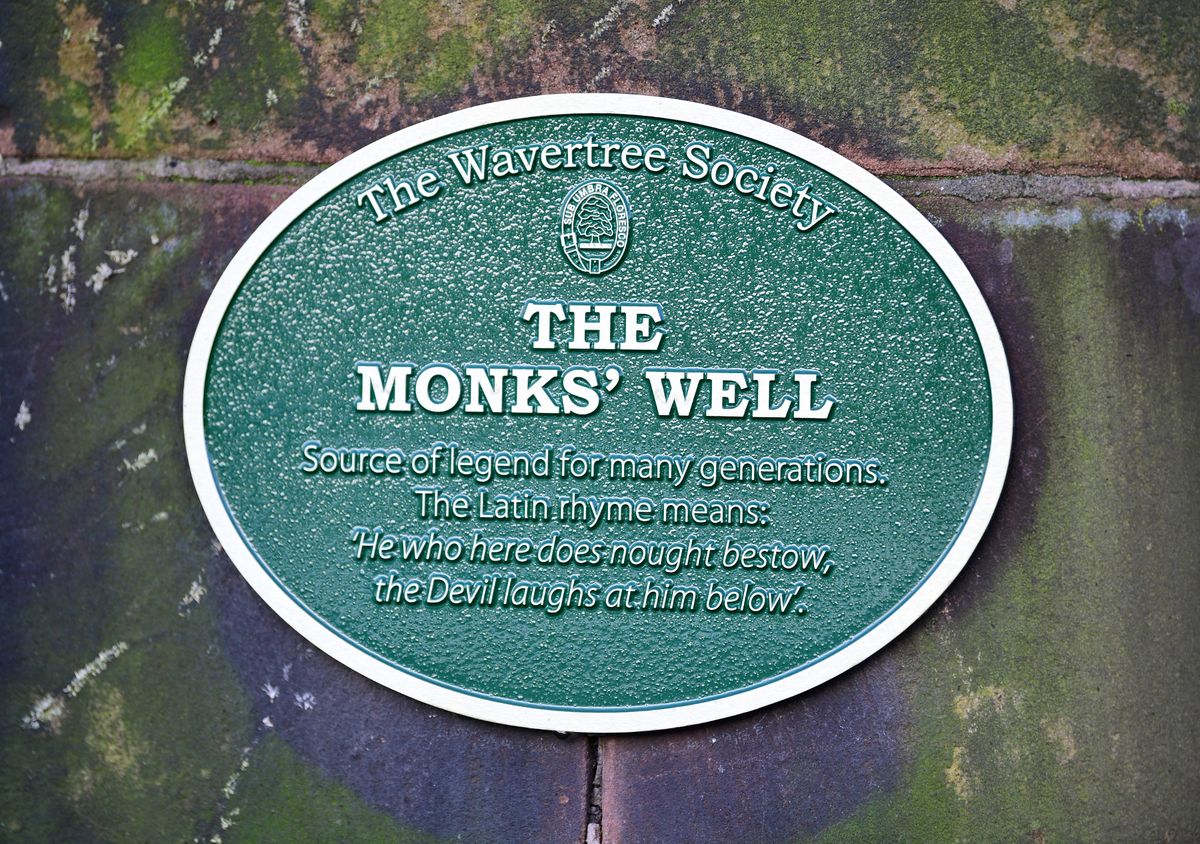

Passerbys who stop to look at the well may see an inscription in the sandstone which reads: “Qui non dat quod Habet, Daemon Infta Ridet”, which means, “He who here does nought bestow, the Devil laughs at him below’”.

It is thought that visitors to the well were expected to pay donations of money, food, or goods.

The Latin rhyme on the well translates to, ‘He who here does nought bestow, the Devil laughs at him below’.(Image: Andrew Teebay Liverpool Echo)

Professor Martin Heale said: “The main inscription on the well is one of its many mysteries. It is in modern lettering, but is said to have replaced an earlier inscription. However, some nineteenth-century accounts give the previous inscription as ‘Daemon infra videt’ which translates to ‘a demon within sees’.

“The presence of an evil spirit within the well does not tally with medieval ideas of holy wells, and may be a later conceit. But it harks back to the notion that one should make a donation when on pilgrimage, as a way of honouring the site and saints associated with it.”