Andrew M Dorman argues that the UK should reduce its reliance on the US for its defence and invest in and strenghten its own capabilities following the geopolitical tensions at Davos.

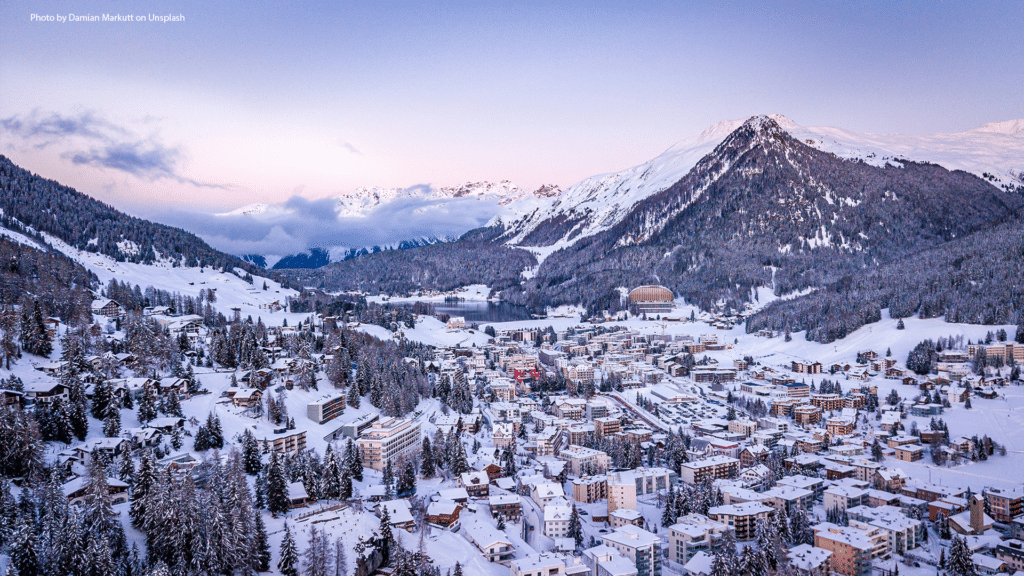

This year’s annual Davos meeting may well have resolved Keir Starmer’s defence dilemma. As ministers, civil servants and the service chiefs returned from the Christmas break, there were broadly two schools of thought on the future of the so-called ‘special relationship’ with the United States.

For many, the current period represents an aberration, a challenging time for US-UK relations at the political level due primarily to Donald Trump becoming the 47th President in January 2025. Proponents of this school believe that this relationship can be preserved, but it will by no means be an insignificant challenge. They point to previous points in history, typically the 1956 Suez Crisis where the Eisenhower administration unpicked the Anglo-French operation, and comfort themselves in the belief that they have already got through one year with Trump not taking the Russian side in the Ukraine War, backing down somewhat over his demands over the annexation of Greenland and also his threats over tariffs.

Following this logic, this school believes that all Britain has to do is see out the remaining three years before a return to some form of normality. The sensible way forward is therefore to duck and evade, to avoid directly challenging the President, to seek to mollify his wilder ideas quietly in the margins and stall for time. They take comfort in the fact that, below the political level, US-UK military relations remain strong.

This means producing a defence investment plan that appeases Trump’s demands for NATO allies to upscale their defence spending – but balancing it through the usual tricks of delay, making bold assumptions about efficiency savings and the sale of surplus defence land, and hoping that the NATO planning assumption about further Russian adventurism in the short-term is wrong.

The appeal of this approach is that it avoids making difficult decisions that the second school of thought believes need to be made now. Starting to unpick 80 years of increasingly close defence cooperation will be both costly and potentially take a considerable amount of time and effort.

For the other school, a return to some form of normality in 2029 with a new President is extremely unlikely. First, there was no guarantee that a future president would favour the transatlantic partnership. Amongst the leading Republicans this looks doubtful. The Vice-President JD Vance is more isolationist than Trump, whilst Trump’s eldest son is viewed as a continuation of his father. Moreover, even someone like the current Secretary of State, Marco Rubio, a more mainstream China hawk, is likely to be less focused on Europe.

Currently there are no obvious Democrat frontrunners, but a Biden-type Democrat seems unlikely. If they are drawn from the progressive wing of the party, they are unlikely to particularly supportive of the ‘special relationship’, with its links to the old world, whilst someone drawn from the more traditional liberal wing is most likely to be domestically focused.

Interestingly, what both schools of thought have in common is their assumption that Trump remains in office until 2029. There is no guarantee of this. Given his age and health, there is the very possibility that the Vice President may have to replace him earlier, thereby pushing the US towards a more isolationist stance.

Choosing whether to stick with the US and hoping for the best or starting the great divorce is probably one of the most important, if not the most important, decisions that Starmer will need to make. Events in January reinforce the importance of the decision.

What the first month of 2026 has shown is a Trump administration increasingly unrestrained. Trump’s demands for ownership of Greenland, both before and at the Davos meeting, have been accompanied by threats of tariffs on eight allies including the UK. Trump’s language about the unreliability of NATO and his proposed Peace Council represent major attacks on the existing rules-based system, and his threats against Iran all point to greater instability. In the background, the new US National Defense Strategy reinforces the language of the earlier National Security Strategy with the US focus being on the Western hemisphere and the expectation that allies elsewhere will be left to do far more.

At the same time, US support for Ukraine remains tepid at best and there is an expectation that any peace deal between Russia and Ukraine would require the deployment of a significant British military commitment to safeguard the peace. The provision of any British force is problematic at best.

The current unpublished defence investment plan, which was supposed to have been released last autumn, remains unaffordable. Based on current assumptions, it looks as though the UK can afford an army or a navy but not both. The former is needed for any peace deal over Ukraine whilst the latter is needed to monitor and protect the UK’s vulnerable offshore infrastructure.

Davos should therefore have confirmed to Keir Starmer that Britain will need to both rethink its dependence on the US and the slow pace of rearmament. Obfuscation and the hope for a return to the ‘special relationship’ in 2029 looks unlikely and alternative partnerships, particularly amongst the middle powers as Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney suggested, looks a far safer way forward.

By Andrew Dorman, Professor of International Security, King’s College London.