Ireland’s Naval Service has begun deploying warships, supported by Air Corps patrols, on an almost permanent basis in the Irish Sea to protect the gas interconnector pipeline that powers much of the country, amid mounting concerns about potential Russian sabotage.

Shipping vessels deemed a possible threat are now being monitored up to 72 hours before entering the Irish Sea or waters close to Ireland, while a section of the gas interconnector south of the Isle of Man is under continuous surveillance for suspicious activity.

Military and security officials fear that Russia could target undersea cables or pipelines by planting explosives or damaging them by dragging anchors along the seabed, tactics viewed as part of the Kremlin’s escalating “hybrid war” against Europe.

The perceived threat has intensified as Ireland prepares to assume the rotating presidency of the European Union in July. Emergency planners believe that damage to the interconnector could result in rolling blackouts lasting months, with severe and potentially irreparable consequences for the Irish economy.

All marine traffic entering the Irish Sea and Ireland’s exclusive economic zone is now being tracked by the Naval Service using satellite intelligence, radar and air patrols. These measures form part of a wider security overhaul of critical infrastructure ahead of the EU presidency, which intelligence officials believe could increase Ireland’s attractiveness as a target for Russia and its proxies.

The Department of Transport recently led a tabletop exercise examining a hypothetical physical blockade of Dublin Port. The exercise, involving multiple government departments, identified serious vulnerabilities and co-ordination challenges in the event of a significant incident in the Irish Sea.

Keir Giles, a senior consulting fellow at Chatham House, a London-based think tank, said recent global developments had rendered once-unthinkable scenarios plausible.

“Anyone who says ‘that couldn’t happen’ should look at world events over the past year and count how many things would have seemed too ridiculous to contemplate the day before they occurred,” he said.

“There is a tendency to assume that Russia’s activities are confined to the far eastern edge of Europe, but when you look at the political return on investment, the softest targets can often be the most attractive.”

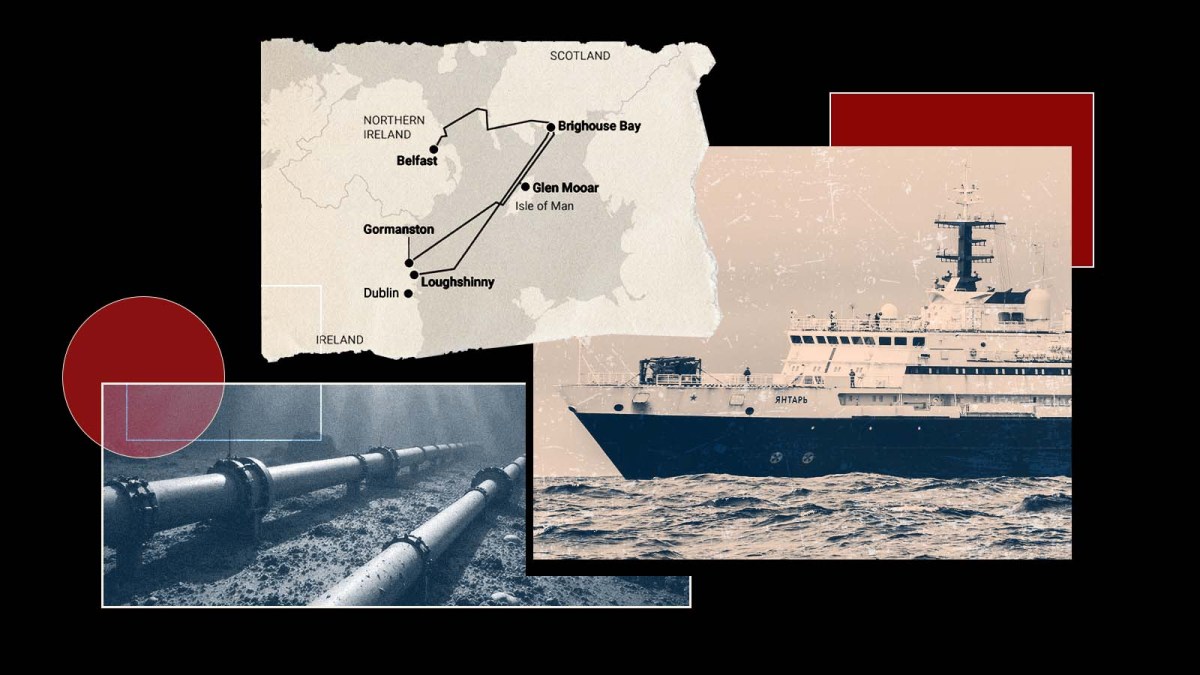

The Russian ship Yantar

STEFAN ROUSSEAU/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

Heightened security measures have been in place since November 2024, when the Yantar, a Russian intelligence-gathering vessel, was detected in the Irish Sea. The ship was tracked from Russia’s Kola Peninsula, past Norway and through the English Channel, before entering the Irish Sea near the Isle of Man.

At one point, the Yantar briefly activated its transponder while loitering near a section of the gas interconnector that is exposed above the seabed. The behaviour prompted the Royal Navy to order a hunter-killer submarine to surface beside the Russian vessel. Specialist divers were subsequently deployed to inspect the pipeline for explosives.

The incident was a key factor in the Irish government’s decision to proceed with plans for a liquefied natural gas terminal at Shannon. Micheál Martin, the taoiseach, has since described the project as a “security imperative”.

Micheál Martin met the President Zelensky during the Ukrainian leader’s visit to Ireland in December

LIAM MCBURNEY/PA

Irish intelligence agencies also point to a series of hybrid operations attributed to Russia that appear designed to undermine public confidence in the state’s security institutions. During a visit to Dublin by President Zelensky of Ukraine, last December, five large military-grade drones believed to be operated by Russian intelligence flew over the Irish naval vessel LÉ William Butler Yeats for nearly an hour while it patrolled Dublin Bay.

The incident, which is understood to be the first time Russia has targeted the Ukrainian leader during an official visit to an EU capital, prompted alarm among European intelligence services. It remains under investigation by garda intelligence and the Irish Military Intelligence Service.

Neil Robinson, a Russia specialist at the University of Limerick, said a high-profile operation aimed at exposing Europe’s vulnerabilities should not come as a surprise.

“Ireland would be an obvious choice,” he said. “Elements of its physical infrastructure are particularly exposed, some of it is nationally critical and some important to Europe more broadly. With the country approaching its EU presidency, the incentives are clear. If Russia wishes to fire a warning shot at Europe, the likelihood of it being directed at Ireland is relatively high and we should be responding accordingly.”