‘This time I was a different beast entering those four walls of pain and sorrow’

05:51, 05 Feb 2026Updated 06:49, 05 Feb 2026

John Fury was jailed for 11 years after gouging a man’s eye out

As he was led from the dock John Fury broke into a rendition of the old Tom Jones hit ‘Green Green Grass of Home’. It was an odd reaction for a man who’d just been sentenced to 11 years in jail.

But then again Fury had been bracing himself for much worse. Facing justice for the brutal crime of gouging a man’s eye out, the former bare knuckle boxer feared he could be slapped with a notorious Imprisonment for Public Protection sentence and face a potentially unlimited amount of time behind bars.

So 11 years was the let-off the father-of-six had been praying for. Now he knew if he kept his nose clean he could be reunited with his family in just half that time.

“This time I was a different beast entering those four walls of pain and sorrow, stupidity and hatred; I was no longer against the world, I just wanted to be back in it,” he wrote in his autobiography When Fury Takes Over.

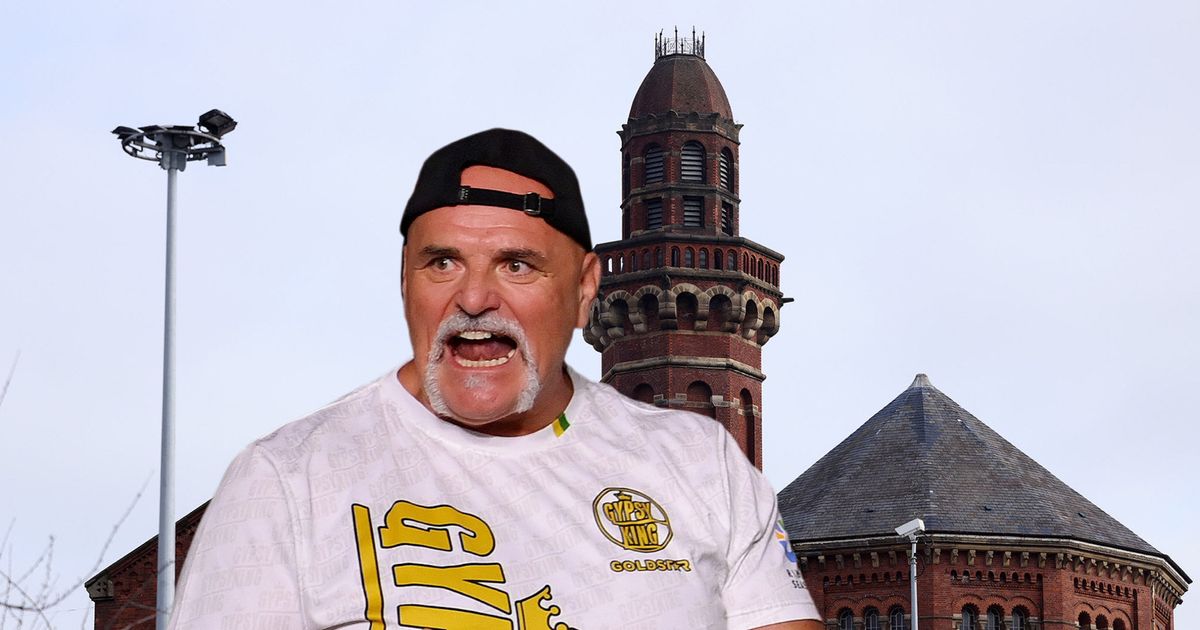

John Fury pictured after his arrest

Fury, the father and trainer of former heavyweight world champ Tyson Fury, was sent down after he left fellow Traveller Oathie Sykes half-blind during a fight in July 2010. The pair had been pals, but had had a violent bust-up over a bottle of beer during a trip to Cyprus in 1999.

And when the they crossed paths at a car auction in Belle Vue in July 2010, the simmering feud erupted once more. After insults and punches were hurled Fury grabbed Mr Sykes by his shoulder-length hair and gripped him in a headlock.

“It was like he was trying to pull his finger into my brains through my socket,” Mr Sykes said. “I was screaming, ‘Please stop, you’re hurting me. After that he tried to take my other eye – he tried to blind me, sir, not once he tried to blind me, twice.”

How the M.E.N. reported Fury’s conviction

With Tyson looking on from the public gallery, Fury, then of Wilmslow, begged the judge for mercy after admitting a charge of GBH. “I’m worried about my son,” he said as he choked back the tears. “His boxing career is on the line.”

Referring to Mr Sykes, he added: “If I could give my own eye to him to get back to my children I would do – I’m begging you for my life.”

Judge Michael Henshell said Fury had been ‘cold-blooded’ in inflicting the ‘catastrophic injury’. But his tearful pleas appeared to have some impact with the judge handing down a more lenient sentence than might have been expected.

It was Fury’s third spell in prison – and he vowed it would be his last. But his determination to stay out of trouble was tested within the first week of arriving at Strangeways.

While exercising in the prison gym, Fury, then in mid 40s and by his own admission carrying a bit of weight, was approached by ‘a lifer, a bodybuilder with huge thighs and arms like tree-trunks’ who demanded he give up the treadmill he was running on.

“I’m not looking for trouble… but there are certain unofficial laws in prison that you need to observe,” Fury wrote of the encounter. “One is, no matter how small you may be and no matter how big your challenger is, unless you want to be treated like a b**** for the rest of your time, you must put up a fight if the fight comes to you.”

John Fury has written extensively about his time in prison

At first Fury made as if to walk off ‘as if I’ve deferred to him’. But it was just a ploy.

“I swing round, hit him clean on the temple and he goes down like a big lump,” he wrote. “For a moment I’m worried I might have killed him. I slap his face a bit and he groans as he begins to come to. ‘Come on, come on wake up, you big Jessie. You’re not dead, you’ve just been knocked out, that’s all’.”

Worried the guards would notice what had happened, Fury dragged the big man to his feet and sent him packing. But before he did so he couldn’t resist offering a few words of advice in his own inimitable style.

“You’ve learnt something today, big fella,’ he told his would-be opponent. “Never tangle with a guy who has fought for a living and eats free-range eggs – you’ll never win. And one more thing. Next time you pick on someone smaller than you, think twice about it, as John Fury will be watching you, and next time I may hurt you for real.”

Fury said it was the only occasion he had to ‘physically assert’ while locked up. Instead he passed the majority of his sentence trying ‘to learn as much as I could’.

He took courses in welding, plumbing, kitchen-fitting, plastering, bricklaying and painting and decorating. Despite being ‘anti-tech’ he even learned how to use a lap top.

And with plenty of time on his hands, Fury also took up reading. George Orwell’s 1984 was a particularly favourite, as were Jeffrey Archer’s prison diaries.

But the book he turned to time and time again was the Bible. Raised in a deeply religious family, Fury says his faith helped him ‘find a way through the darkness’.

“When I went to prison… I never questioned my faith, nor tried to blame it on God that he had landed me in such a horrible place,” he writes. “It was my actions, and my actions alone that had taken me there.”

Towards the end of his sentence Fury was moved to an open prison and began to take pride in helping other inmates. Seemingly humbled by his experience, by then, he writes, he was a ‘very different individual’

“Instead of losing myself to a deep depression, giving vent to my rage and feeling sorry for myself, I had found a kind of peace by helping others manage their thinking and depression.”

But when it came time for his release, Fury found it hard to adapt to life as a free man and feared he had become ‘semi-institutionalized’.

“When I finally came out of prison as a 49-year-old man, that first week back in society was very difficult,” he writes. “I felt like going back to my cell and locking myself in.

“I didn’t feel like a father, I had a distinct sense of disconnection because I’d been on my own for so long. I now felt numb, dirty, horrible and useless, like a waste of space.”

It was clear the time spent inside had taken a heavy toll on him. But eventually he adjusted. He returned to his farm and said he found peace spending time with his animals and grandchildren.

“It was to be a solid year before I began to return to my former self and feel a sense of belonging again,” he wrote. “That’s the price you pay for doing time in prison.”