The Second World War left former colonial European powers decimated, setting the stage for two superpowers to emerge, writes Manchester University history lecturer Dr Louise Clare

06:35, 08 May 2025Updated 06:38, 08 May 2025

Winston Churchill with the Royal Family on VE Day(Image: Hulton Archive)

Winston Churchill with the Royal Family on VE Day(Image: Hulton Archive)

Winston Churchill and Adolf Hitler did not agree on many things.

They were ideological opposites and staunch enemies – serving on opposing sides in World War One before leading their countries in World War Two.

However, both leaders predicted that, because of World War Two’s impact, there would be two spheres of influence post-1945, two superpowers. And given the state of the major European powers by VE Day, financially and militarily, the economic devastation and loss of life, neither would be European.

In March 1946, Churchill stated: “From Stettin in the Baltic, to Trieste in the Adriatic, an iron curtain has descended across the continent.”

Meanwhile, Iin his Political Testament in April 1945, Hitler wrote: “After the collapse of the German Reich, and until there is a rise in nationalism in Asia, Africa or Latin America, there will only be two powers in the world: The United States and Soviet Russia. Through the laws of history and geographical position these giants are destined to struggle with each other either through war, or through rivalry in economics and political ideas.”

Indeed, following the war, colonial powers Britain and France were facing bankruptcy, decolonised. The conflict had created a clear break with international power dynamics and the 1939 status quo.

With former colonial European powers essentially out of the game, the new superpowers became the USA and the USSR, just as Hitler predicted. This new international power dynamic would have a profound impact on post-1945 Europe.

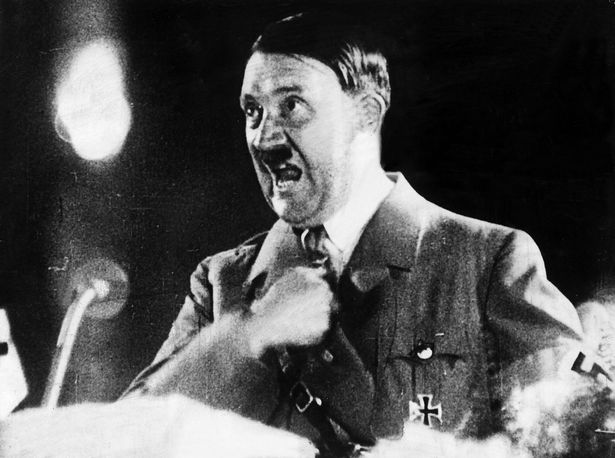

Adolf Hitler predicted the rise of the USA and USSR as the two post-war superpowers

Adolf Hitler predicted the rise of the USA and USSR as the two post-war superpowers

This was not only through the ‘Big Three’ – Britain, the USA and the USSR – carving up Germany at the Yalta and Potsdam Conferences, but through power blocs. Eastern European states were under the USSR’s sphere of influence and Western European states under the USA’s.

Thus, the tone was being set for the ideological and economic struggle between the USSR and the USA, East and West, Capitalism v. Communism, and Europe was becoming the stage where these struggles would be acted out in the Cold War theatre.

Although relative peace followed VE Day amongst European powers, Europe itself – especially Germany – became a focal point of East-West tensions.

This was from the Cold War’s early days, after Germany’s division into East, (USSR-controlled) and West (initially Britain, France and USA-controlled), and Berlin’s division into East and West. First, there was the Berlin Airlift, 1948 -1949, when Soviet forces blockaded access to the Allied-sector of Berlin and British and US forces airlifted in supplies. Then, in 1961, tensions rose again and Churchill’s ‘Iron Curtain’ became a physical reality – with Soviet-controlled forces erecting the Berlin Wall, separating East and West Berlin.

The Berlin Wall, August 6, 1984.(Image: Mirrorpix)

The Berlin Wall, August 6, 1984.(Image: Mirrorpix)

This reality, as the two superpowers vied for influence in the midst of the Cold War, meant certain Europeans experienced a loss of personal freedoms with their movement restricted.

Therefore, not only was the peace which VE Day promised being tested, but Europeans became a bigger and bigger part of the superpower ideological struggle.

This ideological struggle soon became a power struggle and once again World War Two’s impact was instrumental. Facing bankruptcy, many European powers withdrew from Empire, leaving power vacuums, theatres for USA-USSR proxy wars, whilst Europeans focused on their decimated economies and around 9 to 10.3 million European war dead.

However, the decline of these empires did not exclude the respective European powers from playing a significant Cold War role. Britain and France still held considerable geopolitical influence and experience – attractive attributes to the USA. Thus, France’s and Britain’s economic recovery, alongside West Germany’s, became a key piece in the USA’s Cold War foreign policy jigsaw, vital to their Containment Policy of stemming the tide of Communism.

With these ongoing ideological, economic and military Cold War tensions dividing Europe, one could be forgiven for assuming the peace which VE Day and the end of World War Two promised was short-lived, the war only creating further division. Yet, with the European continent apparently divided – a division lasting over 40 years – the 1957 signing of the Treaty of Rome, creating the European Economic Community (EEC), ushered in a new era of European co-operation, laying the foundations for the European Union.

The flag of the European Economic Community/EU

The flag of the European Economic Community/EU

Despite Britain’s initial exclusion from the Community by President Charles de Gaulle’s veto, the Community created a sense of unity amongst European powers as their continent became a Cold War theatre.

This, alongside aid programmes the superpowers offered, helped many European powers such as Britain, France and West Germany to prosper post-1945. In 1948, ‘GDP per head […] was 35% higher in real terms than in 1900’ in Britain, historian Peter Clarke noted. World War Two cleared up residual unemployment from the pre-1939 years of recession. Coupled to this, 1948 saw the NHS’ formation and many other European nations followed suit. This care ‘from the cradle to the grave’ in Britain and programmes such as free secondary education for all, brought the promises of a better society, making Churchill’s and the nation’s ‘blood, sweat and toil’ seemingly worthwhile.

World War Two’s impact therefore ushered in a new geopolitical dynamic, lasting over 40 years, bringing division to a continent, the landscape of which bore the scars of two World Wars. Nonetheless, some Europeans retained some unity and independence through the EEC, maintaining defence rights and improved welfare systems – many existing still in similar forms today.

It was this unity which many historians and commentators believed would be under threat when on 23 June 2016, Britons voted to leave the EU. This set alarm bells ringing across European capitals. To many, it appeared Europe was being split once more, with the potential of other member states leaving, leading to further fragmentation, and ultimately, the collapse of the EU after its long history, dating back to 1957. What followed was a series of cultural references being made, across media outlets, to the consequences of prior disunity in Europe, witnessed across two World Wars and the Cold War.

As Britain formally left the EU on 31 January 2020, these references continued in various analyses, which were already underway, investigating the impact of Britain’s break with Europe. Indeed, the impact on a variety of issues from trade, citizenship, immigration and defence to name a few, were examined and discussed and commentators are still analysing the longer-term impact.

Resultantly, the commentators’ jury is still out. Ultimately however, as Waltraud Schelkle, Anna Kyriazi, Joseph Ganderson and Argyrios Altiparmakis put it in their 2024 article ‘Brexit – the EU membership crisis that wasn’t?’, the EU can be viewed as a ‘polity that is fragile, yet able to assert porous borders, exercise authority over a diverse membership, and mobilise a modicum of loyalty when the entire integration regime is under threat.’