From its control of minerals that are critical to tech manufacturers, to its near monopoly on essential components for energy generation, China has potential strangleholds over vital supply chains that keep Britain functioning.

But there is one industry where the UK’s huge reliance on the totalitarian state raises lethal concerns, which experts fear has been overlooked: medicines.

About 80 per cent of the key chemicals used to make the entire world’s supply of drugs are produced in China, according to industry sources.

It is these compounds that are turned into active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) which fight disease or numb pain – and most of that processing is done in China too. Even when tablets and syrups are formulated here or in Europe, they depend on powders and liquids sourced from the Communist state.

Most antibiotics originate from China. It is also the source of many key treatments for potentially deadly conditions including sepsis, diabetes and high blood pressure.

British security analysts are growing increasingly alarmed about President Xi Jinping’s ability to weaponise this reliance, by cutting off supplies should the worst happen – if Washington and Beijing’s trade war spirals out of control, or if China invades Taiwan and Western nations try to support the island.

The former deputy head of MI6, Nigel Inkster, admitted last month that China’s power to effectively enforce a medical blockade was a major concern.

“China is a critical supplier of many pharmaceutical products – without them, we’d be in trouble,” he told the BBC. “We’ve seen China’s readiness to exercise this kind of economic coercion before.”

This potential threat is very real, medical experts warned recently. The UK is “perilously vulnerable” to disruptions in shipments of antibiotics, vaccines and painkillers, according to an in-depth report by the Centre for Long-Term Resilience, a London-based think tank.

Chinese factories, such as this one in Sichuan Province, now dominate global pharamceutical production (Photo: Pan Jianyong/VCG)

Chinese factories, such as this one in Sichuan Province, now dominate global pharamceutical production (Photo: Pan Jianyong/VCG)

Why the risk is real and how worst could happen

The UK is becoming “super-reliant” on China for drugs, says Dr Paul-Enguerrand Fady, biosecurity policy manager at the centre.

He is alarmed that the relationship between the two countries has been “increasingly oppositional and even veering towards hostile on specific issues” in recent years.

If China ever banned drug exports, it would be a “catastrophe” with “grave consequences,” Fady tells The i Paper. “Many countries would see it effectively as an act of war”.

Shortages would not appear overnight, he says. “There would still be some buffer stocks. The healthcare system doesn’t operate on a just-in-time basis as much as other industries do, so pharmacies aren’t going to suddenly become depleted.”

However, it would immediately create an international race to secure drugs from manufacturers outside China, leading to “a spike in prices as demand far outstrips supply.”

It would also cause “a lot of chaos and confusion” within the UK Government, because there is no centralised system to monitor healthcare supply chains, Fady explains. “We don’t know what we have, where it is, what its expiry date is, what form it takes, and when we’re next expecting a shipment of it, where that shipment is or where it’s coming from.”

And if such a crisis lasted for months, eventually stocks would run out. People could die.

Cutting off healthcare supplies would be an “unprecedented” act in modern history, but China has already started weaponising trade.

In 2023, it banned any exports to the US of technology to extract and separate critical minerals, which are vital for defence and tech firms. Last month it placed restrictions on the sales of seven rare earth elements to any foreign nations, in response to Donald Trump’s tariffs.

Concerns about APIs being exploited in this way have been growing in the US since the pandemic. After Donald Trump blocked people from travelling from China to the US, to prevent the spread of coronavirus, Beijing’s state media threatened to ban medical exports and make Americans “fall into the hell” of an epidemic.

A cross-party group of American senators warned last year that more than a quarter of essential drugs in the US, including medications for cancer and heart disease, rely on key ingredients from China or unknown sources – placing supplies at “very high risk” of disruption.

About 80 per cent of the world’s medicines are thought to depend on Chinese chemicals or active ingredients (Photo: Yuan Chen/VCG)

About 80 per cent of the world’s medicines are thought to depend on Chinese chemicals or active ingredients (Photo: Yuan Chen/VCG)

The danger to the UK

Awareness has been growing more slowly in the UK. But a report by the Civitas think tank in 2022 warned of China’s “potential ‘chokehold’ risks through control of supplies”. Fears of Britain being sucked into the US-China trade war have increased the sense of urgency.

It was fortunate that worldwide Covid-19 lockdowns did not hamper the UK’s medication supplies more severely, especially as the pandemic originated in China.

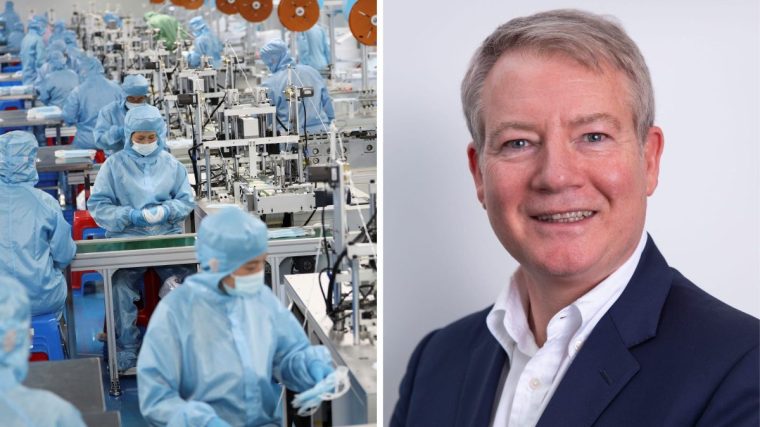

However, Dr Darren Mann – a surgeon who served as medical director for the national PPE Taskforce during the pandemic – vividly remembers the sense of panic among officials trying to source personal protective equipment for the NHS and other key workers.

“There was a complete collapse of PPE supply at the time when demand was highest,” Mann tells The i Paper.

Now, he warns: “Imagine if that were penicillin.”

Indeed, just a single pencillin factory is left in the West, outside the small Austrian town of Kundl.

Dr Darren Mann led efforts to source PPE during the pandemic, when supplies from China were disrupted (Photos: Getty/Achilles)

Dr Darren Mann led efforts to source PPE during the pandemic, when supplies from China were disrupted (Photos: Getty/Achilles)

“We need to accept that we’re entering a very dangerous period of world history,” says Mann, so the chances of China imposing export restrictions during a dispute can’t be dismissed. “The impact would be huge, and the likelihood of it happening is now many times higher than it was.”

The “astonishing” complexity of what goes into a single pill makes it easy to miss weak spots in the system, says Mann, who is now a senior adviser at the supply-chain risk management firm Achilles. “It’s a bit from here, a bit from there, another ingredient from here, then it goes back to the first place, then it comes here to be mixed.”

Mann praises civil servants who have been working hard to map NHS supply chains since the pandemic. The problem, he says, is that “governments don’t import, companies do”.

He accuses the private sector of “wilful” denial over geopolitical risks, driven by profits – because API manufacturing costs are 35 to 40 per cent lower in China compared to the US, for example.

“We’re overlooking that critical import suppliers might actually be from a potential adversary,” he argues. “People have chosen not to look, because traditional procurement practices around value and cost have taken us to parts of the world that we now may find ourselves in hostilities with.”

Europe needs lots of new API factories, like this one being built in Denmark by Novo Nordisk (Photo: Sergei Gapon/AFP)

Europe needs lots of new API factories, like this one being built in Denmark by Novo Nordisk (Photo: Sergei Gapon/AFP)

Calls for Government help

Leading figures in the pharmaceutical industry blame successive prime ministers for not doing protecting and building up sovereign production capacity.

Mark Samuels, chief executive of the trade association Medicines UK, agrees that the UK would be in trouble “if we were in a hybrid conflict or worse” with China, and needs to prioritise healthcare supplies strategically such as defence.

He says that although ministers have financially incentivised the discovery and development of exciting new drugs by high-tech labs, companies have moved production abroad for older medicines which are less profitable but still essential – typically to China.

Previous governments “have entirely focused on the new medicines of tomorrow, and failed to consider the everyday prescription medicines that the NHS relies on,” Samuels argues. “These are life-saving drugs for conditions like diabetes, heart disease, cancer”.

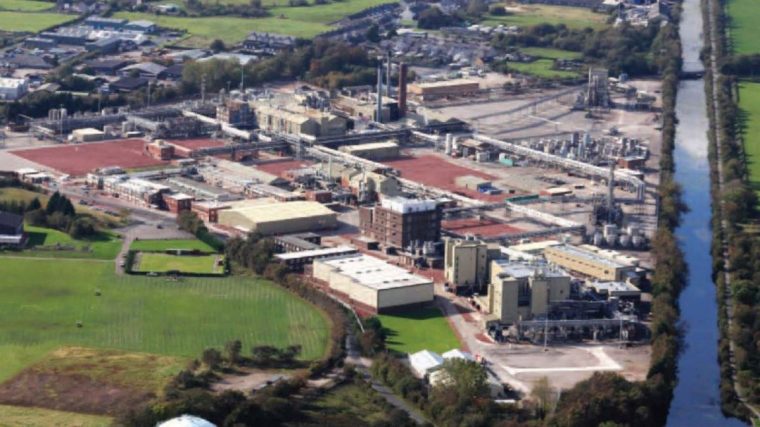

A GSK factory making the antibiotic Zinnat in Ulverston, Cumbria, is due to close next month after a contract expired, with jobs also being lost at Barnard Castle in County Durham.

Although a quarter of the UK’s generic medicines are still manufactured in Britain, he explains that firms are still “reliant on China” for the core ingredients.

He believes a lack of support for this sector is already having an impact on the public. Various supply problems abroad have led to British shortages of some medicines for diabetes, epilepsy and other conditions. The UK has banned the export of 41 drugs because they are needed by patients here.

GSK’s antibiotics factory in Ulverston, Cumbria, will be closing next month (Photo: GSK)

GSK’s antibiotics factory in Ulverston, Cumbria, will be closing next month (Photo: GSK)

What can be done?

The UK’s problems wouldn’t be so severe if its allies made APIs, but most factories have also disappeared from the EU and the US.

Just this week, Europe’s last maker of ingredients for a variety of important antibiotics – used to treat infections such as sepsis – has announced it will be closing its largest factory and shifting production to China. The Danish company Xellia Pharmaceuticals said this was the only way to see off Chinese competition.

Mann says this trend has to be reversed. He admits it will take years if not decades, but he calls on the UK to collaborate with European partners to either “onshore or friendshore” medicine production.

To combat a reliance on China, the EU has announced a Critical Medicines Act, which calls on member governments to consider more than just price when awarding drug contracts.

Before the UK’s general election last summer, the Health and Social Care Select Committee called for ministers to commission an independent review of the medicines supply chain within six months. The Labour Government said in January that it would keep this idea “under consideration,” but has not gone ahead.

The committee’s chair, Liberal Democrat MP Layla Moran, tells The i Paper: “It is very worrying to think that we depend heavily on another country for any of our essential supplies, and all the more so when we are talking about vital pharmaceutical ingredients for medicines.

“This situation puts us at risk of the loss of our essential supplies, in the case of geopolitical events which we may have no control over. The Government must show awareness of these risks by adequately reflecting them in the risk register.”

The Centre for Long-Term Resilience has also recommended the creation of a stockpiling taskforce, and for drug companies to be legally obliged to reveal where their APIs are sourced from.

A Government spokesperson responded: “We’re strengthening the resilience of our medicine supply by offering up to £520m to incentivise the manufacturing of more medicines and diagnostics – and have well-established processes in place to mitigate risks, including using alternative medicines when available.

“We are also actively engaging with partner countries to bolster supply chains – protecting NHS services, patient care and our economic security.”

The Chinese Embassy in London was approached for comment.