KUALA LUMPUR, May 7 — A drug price display mandate for private health care facilities may violate the right of doctors and dentists to dispense medicines to treat patients, two lawyers said.

Abraham Au, a partner at GS Nijar Advocates, said the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering (Price Marking for Drug) Order 2025 interferes with the right of registered medical practitioners and dentists under the Poisons Act 1952 (Act 366) to sell, supply or administer poisons to their patients for the purposes of treatment.

The drug price display order was gazetted by Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Minister Armizan Mohd Ali under Section 10 of the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723) on “price marking”.

“One must understand a medical practitioner/dentist has a distinct and autonomous role under the Poisons Act 1952 to dispense medicine for purposes of treatment (only). They are not selling drugs in the commercial and conventional sense,” Au told CodeBlue.

“Regulation 3, when read as a whole, does not differentiate the sale/administration of drugs in the context of providing treatment to a patient (Section 19 of the Poisons Act) from selling drugs on a retail basis (Section 16 of the Poisons Act).

“As such, whilst the drug display order on the face of it has a reasonable objective, the extension of its application to private health care facilities attracts potential legal anomalies.”

Regulation 3 of the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering (Price Marking for Drug) Order compels private health care facilities or community pharmacies to mark or list the prices of drugs that are either displayed or not displayed for sale, including medicines that are sold, supplied, or administered to consumers.

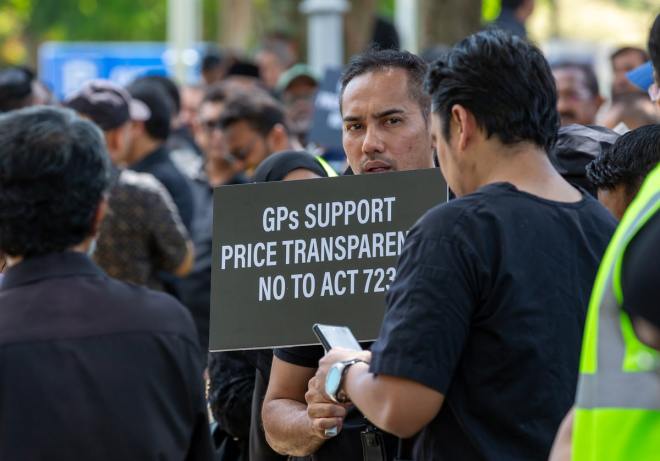

Doctors gather at a rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

Doctors gather at a rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

Genevieve Vanniasingham, an advocate and solicitor practising at RDS Partnership, said that while the drug price display order aims to introduce transparency into drug pricing, the Order “arguably mischaracterises” the doctor-patient relationship by reframing it as a purely commercial transaction between trader and consumer.

“Sections 18, 19, and 21 of Act 366 already provide a specific and self-contained regulatory framework for the sale, supply, and administration of poisons by registered practitioners,” Genevieve told CodeBlue.

“By imposing additional obligations under a general statute, Act 723, which is not designed to regulate private health care facilities and services, the Order risks regulatory overlap and uncertainty.”

Under Act 366, Section 18 deals with restriction on the sale or supply of Part I poisons generally. Section 19 is on the supply of poisons for the purpose of treatment, while Section 21 regulates the sale or supply of Group B poisons.

Doctors gather at a rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

Doctors gather at a rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

Both Au and Genevieve opined that it might possibly be illegal for the government to apply Act 723 to registered medical practitioners or dentists, following a landmark Federal Court ruling this year in the case of Government of Malaysia & Anor v. Dr Vijaendreh a/l Subramaniam & Anor.

In deciding that doctors had the right to dispense ivermectin, the apex court had also ruled that only Act 366, and not the Sale of Drugs Act 1952 (Act 368), applied to registered medical practitioners.

“The Federal Court affirmed that the authority of medical practitioners to sell, supply, and administer Group B poisons stems specifically from Act 366, not Act 368. It is certainly arguable that, by logical extension, applying Act 723, which is general legislation governing commercial practices, to the clinical dispensing rights of medical practitioners may be inconsistent with this ruling,” said Genevieve.

“Each case will, of course, turn on its facts as to whether any such inconsistency arises in practice.”

Au described the Federal Court’s decision in Dr Vijaendreh as a “good starting point”.

“It is arguable that the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 should be limited in its application to the sale of drugs by retail and not in the course of treatment.”

Doctors gather at a rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

Doctors gather at a rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

CodeBlue also asked the legal experts if there was a problem for the drug price display order to use the word “drug” (instead of “poison”) or the word “consumer” (instead of “patient”) and if the Order fundamentally changed the doctor-patient relationship as enshrined in Act 366.

“The answer to this question goes back to whether the Order should be limited to the sale of drugs on a retail basis and not to be extended to sale in the course of medical treatment. Section 19 of the Poisons Act clearly uses the word ‘patient’, which suggests that it falls within a distinct legislative scheme (perhaps under the Private Healthcare Facilities and Services Act 1998 [Act 586]) and cannot be regulated under a general law,” Au told CodeBlue.

Genevieve raised “legal ambiguity” from the use of the term “drug” in the price display order, as its scope potentially overlaps with “poisons” regulated under Act 366.

“More significantly, referring to patients as ‘consumers’, at least rhetorically, recharacterises the doctor-patient relationship as a commercial one,” the lawyer told CodeBlue.

“However, the mere use of the words ‘drug’ and ‘consumer’ are unlikely to alter the substantive nature of the doctor-patient relationship, or at least how that relationship is viewed by the courts.

“The common law has unveiled the nature of that relationship over the course of some 200 years. Additionally, that relationship has been, and continues to be, governed by an important regulatory framework.

“It is therefore more likely that the courts will do their best to read ‘drug’ and ‘consumer’ in a manner most harmonious with the established common law and the concepts in Act 366.”

Drug Price Display Order Enhances Doctor-Patient Relationship

A badge at a doctors’ rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

A badge at a doctors’ rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

Manmohan S Dhillon – a partner at P.S. Ranjan & Co. that mainly deals with medicolegal cases – said the drug price display mandate does not interfere with a doctor’s right to prescribe or dispense medicines to their patients as per Act 366.

Neither does the requirement for the price display of medicines sold at private health care facilities and community pharmacies contradict the Federal Court ruling in Dr Vijaendreh.

“The government can apply Act 723 to doctors,” Manmohan told CodeBlue.

“The drug price display order is for a specific purpose, whereas the Poisons Act has been described as a code by the Federal Court and is of general application to ‘regulate the importation, possession, manufacture, compounding, storage, transport, sale and use of poisons.’ The Poisons Act is not concerned with the display of drug prices.”

CodeBlue also asked if the medicine price display order fundamentally alters the doctor-patient relationship under Act 366 into that of trader and consumer under Act 723.

“The Order enhances the doctor-patient relationship,” said Manmohan in response.

“It’s out in the open – how much you’re charging me – so I can make a decision. I look at your drug price display, I don’t want to see you, I’ll go to a government hospital instead because now I know how much you’re charging me.”

Doctors gather at a rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

Doctors gather at a rally in Putrajaya on May 6, 2025, to protest the Domestic Trade and Cost of Living Ministry’s (KPDN) jurisdiction over mandatory drug price display under the Price Control and Anti-Profiteering Act 2011 (Act 723). Photo by Sam Tham for CodeBlue.

When asked about potential medicolegal risks should patients ignore their doctor’s prescription and demand the cheapest drugs, based on a price list, Manmohan said “doctors should not behave like salesmen.”

He added that doctors have the right not to proceed with treatment if patients refuse to comply with their doctor’s advice.

“I think a patient’s rights should be respected. They should know how much a medicine costs, but that does not take away the doctor’s therapeutic privilege on deciding what to prescribe.”

All three lawyers – Manmohan, Au, and Genevieve – agreed that the MOH lacks the legal authority (“punca kuasa”) to enforce the drug price display order that they said can only be enforced by KPDN, as the domestic trade and cost of living minister’s power under Section 3 of Act 723 is “non-delegable” or cannot be transferred to another minister.

More than 700 private general practitioners (GPs) and specialist doctors held an historic rally in Putrajaya yesterday to protest against KPDN’s jurisdiction over the drug price display mandate that they said should be placed under Act 586 instead.