TIRANA, Albania (AP) — Prime Minister Edi Rama is seeking a fourth term as Albania’s prime minister in a general election on Sunday, after taking on his political nemesis in a boisterous campaign dominated by the country’s uphill effort to join the European Union.

Rama’s Socialist Party says it can deliver EU membership in five years, sticking to an ambitious pledge while battling conservative opponents with public recriminations and competing promises of pay hikes.

Click to Gallery

Voters prepare their ballots during a general election in Tirana, Albania Sunday, May 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

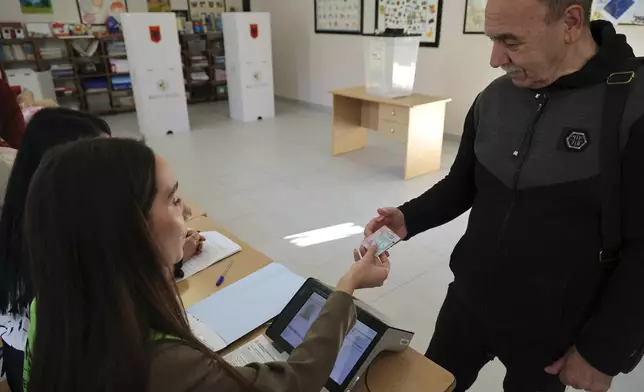

A man prepares to vote during a general election in Tirana, Albania Sunday, May 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

People pass a billboard of the opposition Democratic Party (ASHM) that reads “Vote Grandiose Albania, 1,200 euros average salary, 10% flat tax,” in Tirana, Albania, Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

Supporters of Albania’s Prime Minister Edi Rama wave flags of their country during his main election campaign rally in Tirana, Albania, Friday, May 9, 2025, as his ruling Socialist Party (PS) seeks a fourth term. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

Albania’s Prime Minister Edi Rama speaks during his main election campaign rally in Tirana, Albania, Friday, May 9, 2025, as his ruling Socialist Party (PS) seeks a fourth term. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

An employee handles the mail-in ballots , as Albania is heading to the polls on Sunday with Socialist Prime Minister Edi Rama seeks a fourth term, in Tirana, Albania, Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

Opening up the election to voters abroad for the first time has added to the volatility, along with the appearance of new parties, a shift in campaigning to social media and a recent TikTok ban. And Rama’s opponents have hired a heavy hitter from the United States to steer their campaign.

The country of 2.8 million people, with 3.7 million eligible voters including the diaspora casting ballots for the first time ever by mail, will elect 140 lawmakers to four-year terms, choosing from 2,046 candidates representing 11 political groupings, including three coalitions.

Voting opened at 7 a.m. local time (0500 GMT) and runs until 7 p.m. (1700 GMT).

Rama, 60, secured the start of EU membership negotiations last October and is relying heavily on that momentum. His campaign also highlighted achievements in infrastructure and justice reform.

Under the party slogan, “Albania 2030 in EU, Only with Edi and SP,” Rama insists that full EU accession is possible by 2030 with annual funding of 1 billion euros ($1.13 billion) upon joining.

EU foreign policy chief Kaja Kallas is pressing Albania to continue reforms — particularly in governance and anti-corruption efforts — to stay on track for EU membership.

Commentators are also skeptical. “It is an electoral pledge which is a citizens’ desire,” independent analyst Aleksander Cipa says, describing Rama’s timeline as “not realizable.”

Rama’s main challenger is Sali Berisha, a hoarse-voiced and energetic 80-year-old survivor of Albania’s tumultuous politics. Berisha, a former president and prime minister, has led the conservative Democratic Party of Albania since its founding in 1990, when student protests marked the end of communist isolation.

He argues that Albania still isn’t ready for EU membership. Berisha’s leadership — fraught with party feuds and corruption allegations — and messaging remain contentious. He started the campaign — borrowing from U.S. President Donald Trump — with the slogan “Make Albania Great Again,” but eventually settled on “Grandiose Albania.”

Albania’s Democratic Party hired Chris LaCivita, the veteran Republican political consultant and architect of Trump’s 2024 presidential campaign.

Berisha often appears at rallies wearing a blue baseball cap marked with a No. 1, the party’s position on the ballot. In response, Rama sports a black cap emblazoned with the Socialist Party’s No. 5.

Economic concerns have been central to the campaign.

The Socialists say they will accelerate a tourism boom, from 10 million arrivals in 2024 to 30 million by 2030, diversifying destinations by expanding infrastructure projects.

The Democrats argue that the government’s dismal performance has driven more than 1 million Albanians to leave the county over the past decade.

Both parties have made similar promises: a minimum pension of 200 euros ($225), an average monthly salary of 1,200 euros ($1,365), and a minimum wage of 500 euros ($570) – about 20% or higher than current levels. Berisha also advocates a 10% flat tax, value-added tax refunds for basic food items, a consumer card loaded with government money for retirees to buy basic foodstuffs at discounted prices and other benefits.

The pledges have blurred ideological lines and politics dominated by two parties has encouraged the creation of alternatives. Several newer parties — two from the center-right and two left-wing ones — could emerge as kingmakers, if no major party wins a majority.

But analyst Lutfi Dervishi considers that scenario unlikely.

“It’s a campaign without debate and results without surprises,” he said. “Elections won’t shake up the current scene — neither the system nor the main actors.”

Despite Albania’s significant improvement in Transparency International’s corruption index — rising from 116th in 2013 to 80th in the ranking in 2024 — corruption remains the country’s Achilles’ heel and a stumbling block for European integration.

Sweeping judicial reforms launched in 2016 with support from the EU and U.S. led to investigations and prosecutions of senior officials. Several former ministers, mayors and high-ranking officials have been jailed, while others face ongoing investigations.

Despite promises of cleaner governance, both major parties are fielding candidates facing corruption allegations.

Berisha himself has been charged with corruption and is awaiting trial. In 2021, the U.S. government barred him and his close relatives from entering the country over alleged corruption. The United Kingdom followed suit in 2022.

Last October, Ilir Meta, a former president and now head of the left-wing Freedom Party of Albania that’s allied with Berisha, was arrested on corruption allegations. He’s running for a parliamentary seat in Tirana.

The capital’s mayor, Erion Veliaj, a senior Socialist official, was detained in February amid a corruption investigation involving public funds. He’s not running for reelection. All the accused have denied wrongdoing.

While Rama’s Socialists take credit for the reformed judiciary, Berisha has vowed to dissolve it, describing it as a tool of the Rama government’s selective justice.

Social media has become a primary vehicle for campaigning. Rama hosts daily Facebook livestreams to engage with voters. Berisha has followed suit, though less frequently.

The government has imposed a 12-month ban on TikTok, citing concerns over incitement and online bullying. Opposition parties condemned the move as censorship.

A code of conduct introduced by the Albanian ombudsman to encourage ethical campaigning fell flat as political discourse grew increasingly toxic. Rama described Berisha as a “swamp owl” — a metaphor for graft — while Berisha branded Rama as a “chief gangster.”

Albania’s past elections often have been marred by irregularities, including vote-buying and ballot manipulation.

More than 570 international observers will be monitoring this year’s parliamentary election, highlighting the international community’s stake in ensuring a credible and transparent process.

Voters prepare their ballots during a general election in Tirana, Albania Sunday, May 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

A man prepares to vote during a general election in Tirana, Albania Sunday, May 11, 2025. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

People pass a billboard of the opposition Democratic Party (ASHM) that reads “Vote Grandiose Albania, 1,200 euros average salary, 10% flat tax,” in Tirana, Albania, Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

Supporters of Albania’s Prime Minister Edi Rama wave flags of their country during his main election campaign rally in Tirana, Albania, Friday, May 9, 2025, as his ruling Socialist Party (PS) seeks a fourth term. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

Albania’s Prime Minister Edi Rama speaks during his main election campaign rally in Tirana, Albania, Friday, May 9, 2025, as his ruling Socialist Party (PS) seeks a fourth term. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

An employee handles the mail-in ballots , as Albania is heading to the polls on Sunday with Socialist Prime Minister Edi Rama seeks a fourth term, in Tirana, Albania, Friday, May 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Vlasov Sulaj)

WARSAW, Poland (AP) — In the early months of 2022, as Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine began, millions of Ukrainians — mostly women and children — fled to Poland, where they were met with an extraordinary outpouring of sympathy. Ukrainian flags appeared in windows. Polish volunteers rushed to the border with food, diapers, SIM cards. Some opened their homes to complete strangers.

In the face of calamity, Poland became not just a logistical lifeline for Ukraine, but a paragon of human solidarity.

Three years later, Poland remains one of Ukraine’s staunchest allies — a hub for Western arms deliveries and a vocal defender of Kyiv’s interests. But at home, the tone toward Ukrainians has shifted.

Nearly a million Ukrainian refugees remain in Poland, with roughly 2 million Ukrainian citizens overall in the nation of 38 million people. Many of them arrived before the war as economic migrants.

As Poland heads into a presidential election on May 18, with a second round expected June 1, the growing fatigue with helping Ukrainians has become so noticeable that some of the candidates have judged that they can win more votes by vowing less help for Ukrainians.

“The mood of Polish society has changed towards Ukrainian war refugees,” said Piotr Długosz, a professor of sociology at the Jagiellonian University in Krakow who has carried out research on the views toward Ukrainians across central Europe.

He cited a survey by the Public Opinion Research Center in Warsaw that showed support for helping Ukrainians falling from 94% at the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion in February 2022 to 57% in December 2024.

“Many other studies confirm the change in mood,” he said. “At the same time, it should be remembered that helping refugees after the outbreak of the war was a natural moral reflex, that one should help a neighbor in need. All the more so because Poles remember the crimes committed by Russians against Poles during and after two world wars.”

Among those to transform the shift in mood into campaign politics is conservative candidate Karol Nawrocki, a historian and head of the Institute of National Remembrance who is the Law and Justice party’s chosen candidate and one of the frontrunners.

Law and Justice, still in government in 2022, led the humanitarian response to the crisis along with President Andrzej Duda, a conservative backed by the party who traveled to Kyiv during the war.

As Nawrocki seeks to succeed Duda, he is showing ambivalence toward Ukrainians, stressing the need to defend Polish interests above all else.

Duda and Law and Justice have long admired Donald Trump, and Nawrocki — who was welcomed at the White House by Trump on May 1 — has at times used language that echoes the American president’s.

“Ukraine does not treat us as a partner. It behaves in an indecent and ungrateful way in many respects,” Nawrocki said in January.

After Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s tense visit to the Oval Office in February, Nawrocki declared the Ukrainian leader needed to “rethink” his behavior toward allies.

Last month Nawrocki vowed that if he wins, he will introduce legislation that would prioritize Polish citizens over Ukrainians when there are waits for medical services or schools.

“Polish citizens must have priority,” Nawrocki said in a campaign video. “Poland first. Poles first.”

Further to the right, candidate Sławomir Mentzen and his Confederation party have gone beyond that. He has blamed Ukrainians for overburdened schools, inflated housing prices, and accused them of taking advantage of Polish generosity.

At an April 30 rally of a far-right candidate, Grzegorz Braun, his supporters climbed up to a balcony on city hall in Biała Podlaska and pulled down a Ukrainian flag that had been hanging there since February 2022 as an expression of solidarity.

The political center is adjusting too.

Rafał Trzaskowski, the liberal-minded mayor of Warsaw from Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s centrist party who welcomed Ukrainians to his city in 2022, proposed in January that only Ukrainian refugees who “work, live and pay taxes” in Poland be granted access to the popular “800+” child benefit — 800 zlotys ($210) per month per child.

The requirements were already tightened recently, and some refugee advocates described it as a concession to far-right narratives.

Ukrainian Ambassador to Poland Vasyl Bodnar disputes claims that Ukrainians are taking more than they give. About 35,000 receive support without working, he said, but what they receive is only a fraction of what Ukrainians contribute in taxes. He noted that some 70,000 Ukrainian-run businesses now operate in Poland.

“Ukrainians are helping the Polish economy to develop,” he told The Associated Press.

Małgorzata Bonikowska, president of the Center for International Relations, said that it is normal for tensions to emerge when large numbers of people from different cultures suddenly live and work side-by-side. And Poles, she added, often find Ukrainians pushy or entitled, and that rubs them the wrong way. “But there is still very stable support for helping Ukraine. We truly believe Ukrainians are Europeans, they are like our brothers.”

Rafał Pankowski, a sociologist who heads Never Again, a group that fights xenophobia, has tracked anti-Ukrainian sentiment from the start of the full-scale war. At first, the far right was very isolated in its anti-Ukrainian opinions, he said.

“What is happening this year is harvest time for all those anti-Ukrainian propagandists, and now it goes beyond the far right,” he said.

Kateryna, a 33-year-old Ukrainian who has lived in Poland for years, has seen the change up close. In 2022, strangers often greeted her with sympathetic looks and with the words “Slava Ukraini” (Glory to Ukraine).

But then last fall, a man on a tram cursed her for reading a Ukrainian book. This spring, outside a social security office, another man shoved her and screamed, “No one wants you here.”

Such incidents remain rare — Poles and Ukrainians co-existing on friendly terms is still the norm. But she feels such incidents were unthinkable three years ago.

She asked that her last name not be used because she works as a manager in a company that would require to have clearance to be identified publicly.

Her parents remain in Ukraine, and her brother serves in the army. Like many in the region, she believes Ukrainian resistance is keeping Poland safe by holding the Russians at bay.

Tensions now, she worries, only serve Moscow. “We must stick together,” she said.

FILE – Right-wing candidate Karol Nawrocki, left, takes part in a patriotic demonstration celebrating 1,000 years since the coronation of the first Polish king, Saturday, April 12, 2025 ,in Warsaw, Poland. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski, File)

FILE – People join in a rally of support for Ukrainians in Warsaw, Poland, Monday, Feb. 24, 2025. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski, File)

A man holds a poster that says “Refugees NO pasaran” in Warsaw, Poland, Saturday, May 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski)

A man holds a poster that says “Fascism out” in Warsaw, Poland, Saturday, May 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski)

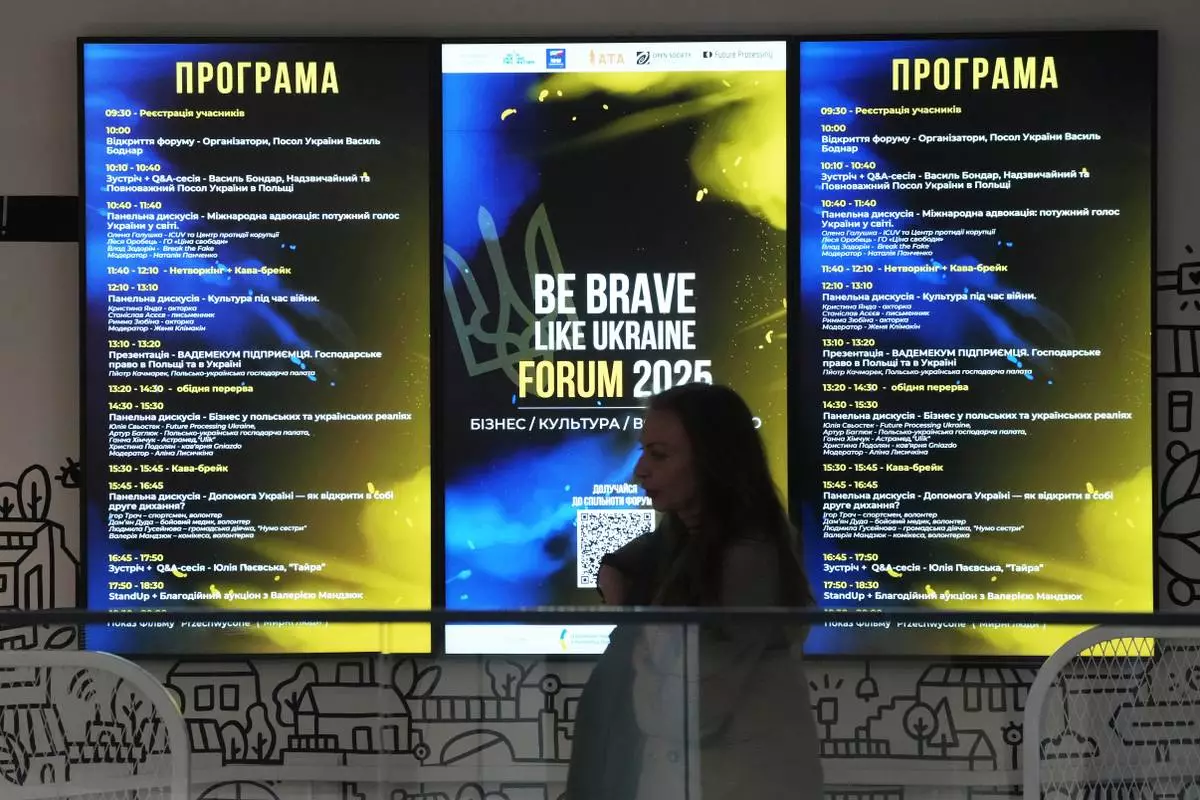

Two people stand near a poster for a forum devoted to Polish-Ukrainian solidarity in Warsaw, Poland, Saturday, May 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski)

A woman stands near a poster in support of Ukraine, in Warsaw, Poland, Saturday, May 10, 2025. (AP Photo/Czarek Sokolowski)