In the present study, which aimed to collect the views of those involved regarding urGS and its implementation, respondents to the questionnaire were balanced between NICU/PICU physicians, clinical geneticists and laboratory geneticists, and respondents were from throughout France, providing a national range of opinion. However, the response rate to the survey was not possible to determine because of the way it was distributed by general learned societies. In addition, access to genetic resources remains a major problem, even beyond the proximity of a laboratory. For example, a respondent reported they had no access to clinical geneticists or genetic counsellors (data not shown), and we can assume that other professionals with no access to a genetics department will not have taken the time to reply to the questionnaire. It cannot also be ruled out that some respondents had prior experience of urGS while working abroad that could affect their responses, urGS was available in a very limited number of countries/centres worldwide; we therefore decided not to quantify this potential bias in order to keep the survey as short as possible, but was not mentioned in any free text comments provided by the respondents.

The first point of note from the results of the survey is that healthcare professionals believe that urGS is relevant in the context of NICUs/PICUs, and that there is a real demand from physicians for its implementation in clinical practice. Physicians seem ready to incorporate urGS for patient management, as they were likely to modify their practices while waiting for results and following the urGS results. However, the present study did not aim specifically to evaluate the impact of implementing urGS, and prospective studies of the clinical utility and cost effectiveness adapted to the French healthcare system are needed. The medical utility demonstrated in the literature [5,6,7,8, 10, 11] is, therefore, in line with the medical interest expressed via the present survey. Furthermore, the results indicate that respondents consider urGS as more relevant for NICU/PICU needs than rGS as a majority of respondents (in particular NICU/PICU physicians) consider 2 weeks (from GS test initiation to a result) to be too long in this context.

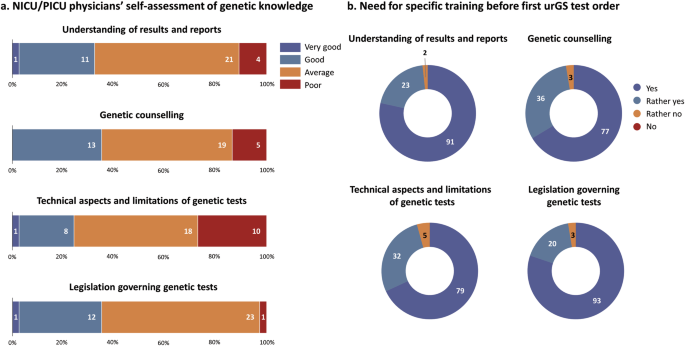

The respondents nearly all agreed on the need for training prior to the first urGS test order. The need for training in non-genetic medical specialties for the routine implementation of genetic tests has already been highlighted in the literature [25]. Although technological advances have rapidly taken place since then, training is still not optimal, as was pointed out by the NICU/PICU physicians in the present study. National training projects have emerged in countries such as Australia and England [26, 27]. In France, the French Genomic Initiative (PFMG2025) has set up a training working group to identify existing resources relevant to training in genomic medicine [28]. The training of future physicians has also improved, with the addition of genomic medicine-related courses to their initial curriculum. Although the preferred type of training (in-person or online) was not investigated herein, it would be important to discuss this locally with geneticists and to make use of existing resources for more in-depth theoretical knowledge [29, 30]. In addition, it is not easy for parents to understand the aim of urGS and what it means, especially in critical care situations [14]. However, the NICU/PICU setting can be turned into an ‘advantage’, with the continuous availability of bedside paramedical healthcare that can support parents experiencing doubts and having unanswered questions [21]; targeted training on genetic testing for these professionals appears particularly relevant.

The respondents agreed that having professional and departmental champions in each centre, as proposed in the literature, to facilitate the test initiation and organisation of rapid genetic analyses [18, 21], was important. The need for multidisciplinary approval of the test order and a discussion once the result has been obtained was expressed. This underlines the will of professionals to work closely together, and the value of having designated champions so that these discussions can take place easily and in a timely manner by relying on the existing network. A network is also mentioned in the literature as an important element for successful implementation and adoption of urGS [21].

Involvement of a clinical geneticist in pre-test information and gathering of consent was favoured as the best option by nearly all geneticists (clinical and/or laboratory), but by only just over half of NICU/PICU physicians. This is in line with the finding herein that half of NICU/PICU physicians consider that they would be able to give pre-test explanations and obtain consent. These data, together with their self-assessed mediocre knowledge of genetics, suggest that targeted training about the genetic aspects, and also the presence of a genetic counsellor, could be appropriate for the test initiation.

Having both a clinical geneticist and a NICU/PICU physician was the solution favoured by both geneticists and NICU/PICU physicians for disclosing the urGS results, although the questionnaire did not distinguish situations of conclusive or inconclusive reports. Here again, the genetic counsellor could support the NICU/PICU physician in charge of the patient in case of the unavailability of a clinical geneticist. Compared with the existing literature [31], the role of genetic counsellors could seem minor but this is probably the consequence of different legal frameworks for these professionals. In France, genetic counsellors are mainly involved in counselling families of patients with diagnosed genetic diseases and in prenatal diagnosis centres; they are rarely involved in the diagnosis of an index case. Nevertheless, their role could evolve to meet the growing needs in genetics. In particular, they could support other non-genetic physicians in providing pre-test information and consent for genetic analyses, for example, in this urGS context. This would increase the possibilities for responding quickly to requests.

Regarding the situations that could lead to urGS test order, a quarter of respondents mentioned clinical indications other than those mentioned in the questionnaire, and critical care situations rather than precise conditions were mentioned (atypical course of a simple condition, ventilatory dependence, etc.). A list of initial indications could be drawn up, but this should not be restrictive. This seems to be the approach adopted internationally, with the selection criterion being children in whom a genetic cause has been suggested [3]. However, preliminary results from an ongoing study suggest that a genetic aetiology had not been evoked initially in up to a third of neonatal intensive care patients with a genetic diagnosis [32].

The view of healthcare professionals on providing results with VUS was mixed, but the majority were against it. It is likely that adding an element of uncertainty to the patient’s already critical situation could be perceived as deleterious. In the literature, VUS of particular interest (i.e. those with a high probability of becoming a diagnosis) in the context of rGS or urGS are often discussed on a case-by-case basis in a multidisciplinary team and included in the laboratory results [3, 33]. A multidisciplinary discussion of VUS of interest could, therefore, be proposed, and decisions made on a case-by-case basis.

Genome-wide analyses may incidentally reveal variants unrelated to the initial indication, which would enable the person or the family members to benefit from preventive measures, including genetic counselling, or care. Under French law, prior to a genetic test, the patient must be informed of this possibility, and they can refuse to be informed about such findings. In the context of NICUs/PICUs, a highly stressful situation, the ability of parents to truly give free and informed consent prior to testing is probably uncertain [14, 34]. The time to report such incidental findings has also been addressed [35]. Some respondents raised the need to be cautious with incidental data, and nearly all were against providing them at the same time as the primary urGS result when the acute clinical situation, to which parental and medical attention is focused, is unrelated. We, therefore, propose that incidental data could be given at a later stage, after having the opportunity to reassess their consent on this matter.

Psychological support was considered important at all but one stage (during urGS test order) by the overwhelming majority of respondents. Parents have little time to understand the implications of urGS, and their expectations of the test are probably different from those of the medical teams. The latter aim to understand and, if possible, treat, whereas parents tend to focus on active treatment [36]. It is important that the expectations of the test are explained, and that medical, paramedical and psychological support is provided. However, there are few full-time psychologists in intensive care and genetics wards, and the present study highlights the needs expressed by NICU/PICU physicians and clinical geneticists to improve care for families in these particular situations. At the very least, we propose that a psychologist trained in genetics take part in the training of care teams, to provide them with the skills needed so that they can provide suitable support. Whenever possible, we support the involvement of either a genetics psychologist or an intensive care psychologist with specific training in the challenges of urGS. Finally, the systematic involvement of a psychologist in tandem with the geneticist/intensivist at key moments, such as when the results are disclosed or after the disclosure, should be a longer-term objective.

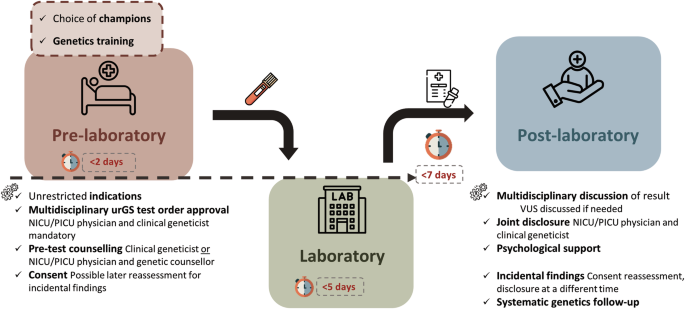

All the points highlighted by the present study are summarised in a workflow proposal (Fig. 5). It is important to note that the present study was based on elements identified in the literature, such as the need for upfront training as well as the importance of having champions highlighted by Australian Genomics [20] and respondents had access to the main references to familiarise themselves with them. Although this may have prevented the identification of new elements, the free-text fields in the questionnaire did not reveal any. The workflow we propose is, therefore, the result of the study and the international literature.

Fig. 5: Proposed workflow for urGS in NICU/PICU setting.

Prior to implementing urGS, champions for the test should be designated within each department and genetics training tailored to the field of practice should be provided. A multidisciplinary approval of urGS test orders should be used on a case-by-case basis. The notion of consent reassessment for incidental findings should be introduced. urGS results should be discussed by a multidisciplinary team for patient management. Results should be disclosed by both NICU/PICU physicians and clinical geneticists. Psychological support for parents/family should be available, especially after the results are disclosed. VUS variants of uncertain significance, urGS ultra-rapid genome sequencing, NICU neonatal intensive care unit, PICU paediatric intensive care unit.

The clinical implementation of urGS is still in its early stages. Each organisational proposal remains specific to a healthcare system and will likely require this type of study for implementation, as well as complementary studies to refine the organisation once it has been implemented. It is imperative to establish a framework while maintaining the necessary flexibility to adapt to the specific needs of NICU/PICU patients and local specificities.

The present study allowed us to define the views of French healthcare professionals on urGS and propose a workflow based on their expectations. Without overestimating the role of genetics, urGS is expected to facilitate the delivery of more personalised and effective neonatal and paediatric intensive care. Ultimately, it will open up new avenues for the diagnosis, management, and treatment of genetic conditions in newborns and children.