Junction changes in the city centre will lay an “obstructed path” that could eventually be used for a tram route MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – MARCH 19: General view of a Metrolink tram on Mosley Street, Manchester city centre on March 19, 2020 in Manchester, England. (Photo by Anthony Devlin/Getty Images)

MANCHESTER, ENGLAND – MARCH 19: General view of a Metrolink tram on Mosley Street, Manchester city centre on March 19, 2020 in Manchester, England. (Photo by Anthony Devlin/Getty Images)

The number one answer when asking anybody in Bristol what they want to improve about the city tends to be public transport and congestion. But then ambitious plans to actually improve public transport in Bristol are almost always met with derision and disbelief.

So recent news, that upcoming changes to city centre junctions will lay an “unbroken path” for a potential tram route, were predictably met with scepticism. One commenter on social media claimed Bristol would be more likely to get a network of “Chuckle Brothers cycle cars” than trams.

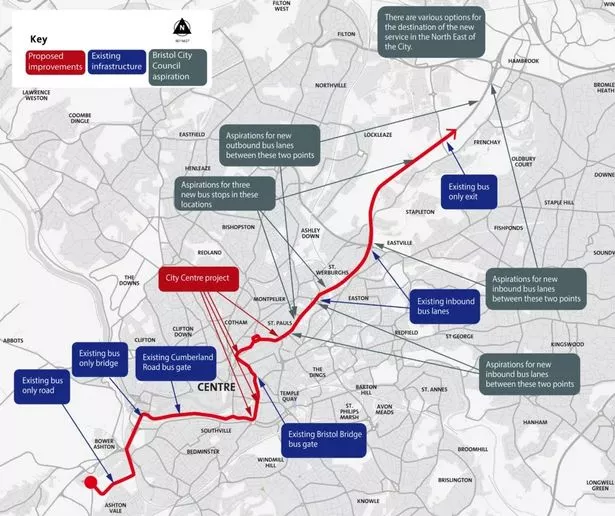

The changes will be rolled out over the next couple of years, and will mean buses can travel from the Long Ashton park and ride in the south-west of Bristol, through the city centre and then to the M32 without ever getting stuck in traffic. This will make eventually building a tram route easier.

However there are a number of hurdles before any construction on tram lines can begin, which if they can be overcome, won’t start until the 2030s at the earliest. And Bristol has endured years of rows over whether Bristol should get an underground, and decades of failed tram plans.

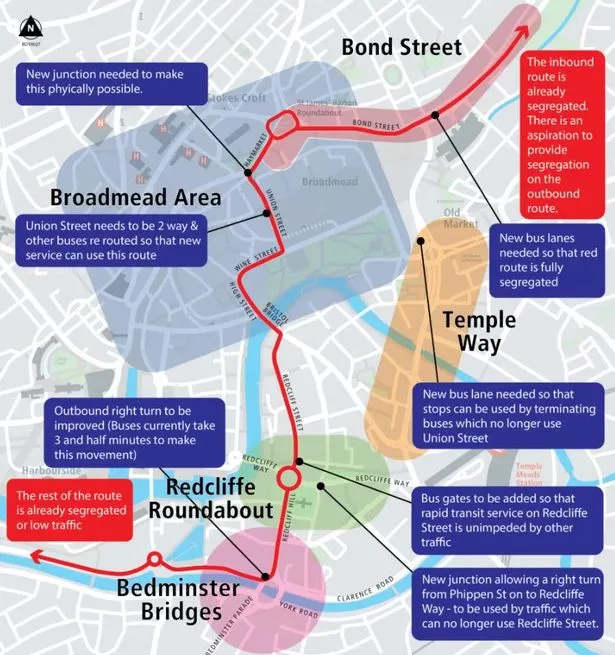

The “red route” has long been an ambition of Bristol City Council. This will run along Cumberland Road, up Redcliff Hill, down Union Street, through a new junction with the Haymarket past Primark, then along Bond Street before getting to the M32 motorway.

The red route would run from the south-west to the north-east(Image: Bristol City Council)

The red route would run from the south-west to the north-east(Image: Bristol City Council) Junctions in the city centre will be changed for the red route(Image: Bristol City Council)

Junctions in the city centre will be changed for the red route(Image: Bristol City Council)

New bus lanes and bus gates were given the green light by councillors on the transport policy committee on Thursday, May 15, who hinted at the longer term benefits of the red route. Green Councillor Emma Edwards said: “This in future could potentially turn into a mass rapid transit route, whatever that might mean — more buses or maybe other modes as well.”

Transport bosses at the West of England Combined Authority are already drawing up plans for a mass transit network. They’ve ruled out options that “involve significant tunnelling”, like an underground, due to concerns about cost. Due to the lengthy planning process the government insists upon, a full business case is expected in either 2029 or 2030, costing £7.8 million.

The final plans could involve a tram network, or “bus rapid transit”, a cheaper alternative. Then there is the question of who will pay the exorbitant costs of actually building anything, which could reach into the billions of pounds.

The current Labour government is tightening the purse strings — but the economy could have improved by then, freeing up more money to invest in public transport infrastructure. A different government could also have been elected by then, with the next general election due in 2029.

Before the Greens took control of Bristol City Council last year, the former Labour mayor Marvin Rees was against the idea of building a tram network, favouring an underground instead. He often said that trams running up Gloucester Road, for example, would cause havoc on neighbouring streets with traffic diverted through residential areas.

Disputes and visceral disdain between Mr Rees and Dan Norris, the former Labour mayor of the West of England, led to years of deadlock until Mr Norris vetoed the underground idea in 2023. And the next local elections in Bristol are due in 2028, when a different party could take control, with new leaders who could also be against the idea of trams.

The new Labour mayor of the West of England, Helen Godwin, was coy in the run up to the regional elections earlier in May about which form of mass transit she preferred. She did claim that she would be best placed to negotiate with the Labour government, due to being in the same party — although this didn’t appear to benefit relationships between Mr Rees and Mr Norris.

Bristol used to have an extensive tram network before the Nazis bombed its power station and the city’s transport planners didn’t bother repairing it, as cars became more popular. Plans to build a tram network were discussed in the 1970s and 80s, which would have been funded privately as businesses bet on rising land values along the proposed routes and near stations.

These were dropped in the early 1990s as the country went into recession. In the early 2000s, trams were again being planned for Bristol, with the first line going from Broadmead to either Almondsbury or Cribbs Causeway. But delays and squabbles between the region’s politicians meant nothing ended up happening — which might sound eerily familiar to today’s problems.

Although around this time other cities did indeed get tram networks funded by the Labour government under Tony Blair. Nottingham for example has a smaller population than Bristol, and a tram network. Croydon, Birmingham and Manchester are other examples too. And Coventry is currently testing a new technology called “very light rail”, which is cheaper and easier to roll out.

But building transport infrastructure is not something the country is generally good at. Last year a report by the Boston Consulting Group found that infrastructure project costs are much higher in the UK than in France, Germany and Spain. Building a high-speed railway line from London to the north of England suffered incredible cost overruns, and will now only end at Birmingham.

Other infrastructure is hard too: building new schools for example in Bristol has proved difficult. One year group at the new Oasis Temple Quarter Academy will spend almost their whole time at the high school in temporary classrooms, as the permanent building has been delayed for so long.

Mr Rees said in his last public speech as mayor that the city suffered from a “debilitating cynicism”. His flagship policy of building an underground never saw spades in the ground, and his decision to move the planned arena means no construction has yet started.

However there is a very valid reason why Bristolians might be cynical and sceptical about promises such as trams. The junction changes along the red route do mean the city is inching closer to the reality of getting a mass transit network, but there is still a lot of track left to travel.

Bristol Live WhatsApp Breaking News and Top Stories

Bristol Live WhatsApp Breaking News and Top Stories

Join Bristol Live’s WhatsApp community for top stories and breaking news sent directly to your phone

Bristol Live is now on WhatsApp and we want you to join our community.

Through the app, we’ll send the latest breaking news, top stories, exclusives and much more straight to your phone.

To join our community you need to already have WhatsApp. All you need to do is click this link and select ‘Join Community’.

No one will be able to see who is signed up and no one can send messages except the Bristol Live team.

We also treat community members to special offers, promotions and adverts from us and our partners. If you don’t like our community, you can check out at any time you like.

To leave our community, click on the name at the top of your screen and choose ‘Exit group’.

If you’re curious, you can read our Privacy Notice.

Click here to join our WhatsApp community.