Race has no biological basis and no effect on the onset or progression of disease.

Being Black doesn’t put you at a greater risk for sickle cell disease; having ancestry from a place with high rates of malaria does. You can have white skin and still have sickle cell disease, especially if you have Mediterranean ancestry. When race is used as a crude proxy, we miss the real risk — we underdiagnose and misdiagnose. We increase medical costs and preventable diseases.

That’s exactly what a study published recently in JAMA Network Open found. The researchers compared a race-neutral equation to detect asthma symptoms in children with one that adjusts for race (the Global Lung Initiative’s 2012 equation). Furthermore, the race-neutral equation identified two to four times as many more Black children with asthma or asthma symptoms as having reduced lung function, making early detection more likely. The study follows similar research that demonstrates the damage caused by race-based clinical calculators, which are based on faulty research.

But it’s not as simple as ignoring race altogether.

Race may not be biological, but as a social construct it affects health in complex ways. We don’t want “color blind” research, which could overlook dangerous trends in at-risk populations. Rather, studies should account for social determinants of health without using race as a crude proxy — such as the societally ingrained idea that sickle cell anemia is a Black disease.

Inside the bruising battle to purge race from a kidney disease calculator

Confounding race with genetics causes doctors to miss treatable ailments. For instance, it was long thought that Black women had a lower chance of successful vaginal birth after a cesarian than white women did.

But researchers got it wrong. The precipitating factor wasn’t race; it was the higher incidence of hypertension, which, unlike race, is treatable.

Hypertension affects nearly half of all women in the United States. If the researchers hadn’t assumed race was causal, they could have helped more women more quickly. In a country with a shockingly high rate of fetal deaths, avoidable gaps in research cannot be tolerated.

The initial research wasn’t necessarily biased — it just didn’t look deep enough. Often in these kinds of cases, the population size wasn’t large enough and scientists made assumptions based on small groups of minorities.

This situation could become worse.

Last November, weeks before Trump won the U.S. election, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine issued new guidelines on the use of race in research. The guidelines came nearly a decade after a medical student noticed the harm of race-adjusted calculations for kidney functioning, which were based on the incorrect belief that Black people have more muscle mass, and three years after the National Kidney Foundation recommended race-neutral calculators.

The key words here are recommendations and guidelines. It’s well-known that these race-adjusted calculators are inaccurate, but there is no mandate preventing their use. Worse, if science fails to improve inclusivity in study design, research will continue to produce inaccurate and harmful clinical tools. Poor diagnostics hurt everyone.

Yet the Trump administration removed FDA draft guidance on diversity in clinical trials — a move that will surely worsen the misuse of race in medicine. The removed FDA draft guidelines were another victim of the Republican Party’s attack on DEI initiatives. It’s misguided and will harm everyone. The guidelines were not limited to race, but also included sex and age. In brief, they called for studies to be representative of the population that would be affected and for the data to be disaggregated, allowing researchers to break it apart and better understand both the root cause of a disease and contributing social factors. This attack on inclusive study design is a hurdle in the fight to remove systemic racial bias from clinical tools.

If the Trump administration and the Republican Party are serious about slashing government spending and curtailing chronic disease, they must make health care and social determinants of health race-neutral — enforcing both the FDA draft guidelines and National Academies guidelines. Doing so is in line with the Trump administration’s campaign promises.

On the other hand, the Republican Party has crippled the funding bodies that could enforce the Nation Academies guidelines. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the National Science Foundation (NSF) could introduce them as part of the criteria for research grants. But with their funding cut, the administration has them in a chokehold — directly opposing promises from the Make America Healthy Again movement.

But regulatory and funding bodies are not the only mechanisms for addressing this problem. Research journals could require adherence to new race-neutral standards as a condition for publication. Academic institutions and ethics review boards can adopt the guidelines as part of their best practices, embedding them in the research approval process.

National Academies calls to change how biomedical research uses race and ethnicity

Even with this executive attack on science, we have many ways to correct race-based medicine.

Individuals and institutions are not powerless. Much of the research has already been corrected. Yet doctors and hospitals are still using incorrect clinical calculators, often because updating clunky hospital systems is tedious.

A 2023 study (preprint) identified 48 clinical calculators, out of which only seven had been modified to exclude race as a predictor. The study also identified six laboratory tests, and 15 medications with race-based guidelines.

Even with these race-neutral calculators available, different hospitals are still using different computer systems and different clinical calculators. Your lung function may be normal at a hospital that still uses race-based calculators and abnormal at one that uses the upgraded, race-neutral model. Major electronic health record providers like Epic, Cerner, and Allscripts, which have historically incorporated race-adjusted clinical calculators, must incorporate the updated, race-neutral calculators into their systems. Centralizing this would require collaboration with software vendors to remove outdated tools and implement universal changes, but it can and must be done.

Epic Systems has acknowledged the error of race-adjusted calculators and works with hospitals systems to update clinical calculators; in 2022 Epic worked with Ochsner Health Network to introduce the race-neutral calculator for kidney function. Allscripts describes their EHR system as customizable — the health care provider can decide to incorporate outdated race-adjusted calculators or the updated race-neutral version. Cerner, which is used by the Department of Defense and the Veterans Administration, also allows systems to customize calculators. Both provide clients a list of calculators, but it’s not always clear which calculator includes race and which does not. It’s imperative to ensure standardized implementation across diverse EHR systems to prevent variability in use. Why are outdated and harmful calculators still on the market?

The problem may seem overwhelming, but recent history proves it solvable. In seven years, there’s been a nearly system-wide adaptation of the new race-neutral measurement for kidney function.

Other measurements have been slow to catch up. A race-neutral spirometry (the tool used to measure pulmonary health by respiratory output) wasn’t recommended by the American Thoracic Society until 2023. Debate over its use and implication is ongoing. The JAMA study on childhood asthma should add haste. The researchers in the 2023 study created an online database for clinicians to check which calculations are race-based.

But the onus cannot be put on already over-stressed and overworked clinicians to do better in an active minefield of bad options. The average time a primary care physician spends with a patient is 18.9 minutes, and that time is even shorter when the patient is younger, publicly insured, Black, or Hispanic. Getting this right is another step toward improving preventive medicine, a practice that the MAHA movement preaches.

Now, more than ever, it’s vital to focus on the facts and to forge ahead. Funding bodies, along with philanthropists, academic institutions, and investors can and should step up. It’s in the best interest of pharmaceutical companies to study diverse populations and follow the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, along with the FDA draft guidelines. The incorrect use of race in medicine hurts everyone. This is not a DEI issue; this is a human issue.

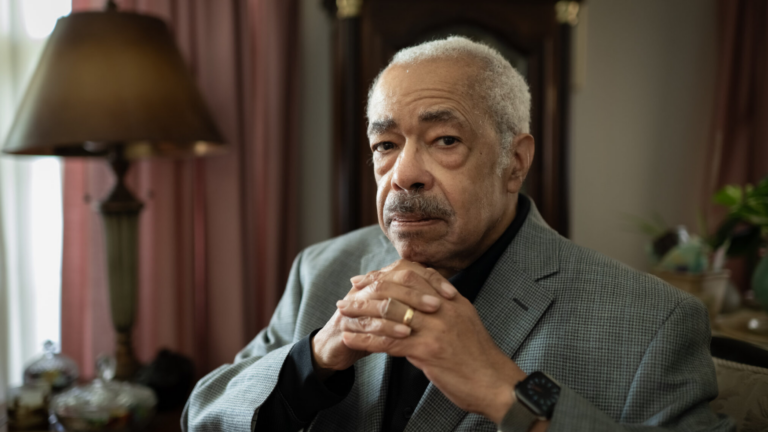

Jennifer Lutz is a journalist and strategic consultant. Richard Carmona, M.D., M.P.H., was 17th surgeon general of the United States and is a distinguished laureate professor at the University of Arizona.