In Moonraker, the third of the James Bond novels, the antagonist, Sir Hugo Drax, passes himself off as a British army veteran turned entrepreneur.

It transpires, however, that he is none other than Graf Hugo von der Drache, a Nazi and Wehrmacht veteran seeking to take revenge on Britons for his country’s defeat. This plot twist may have been no accident, according to an exhibition organised by a 007 fan group in Germany.

For years the “Bond Club” in Wattenscheid, a suburb of the western city of Bochum, has maintained that its home town was the fictional spy’s birthplace. Ian Fleming, the former naval intelligence officer and Sunday Times journalist who wrote the books, was vague on the subject but various fleeting references in the films and elsewhere in the Bond franchise suggest it might have been Wattenscheid, Berlin, Zurich or Glencoe in Scotland. Now the German club argues that Fleming based Drax and several other villains on military industrialists in Nazi Germany whose papers he obtained at the end of the Second World War.

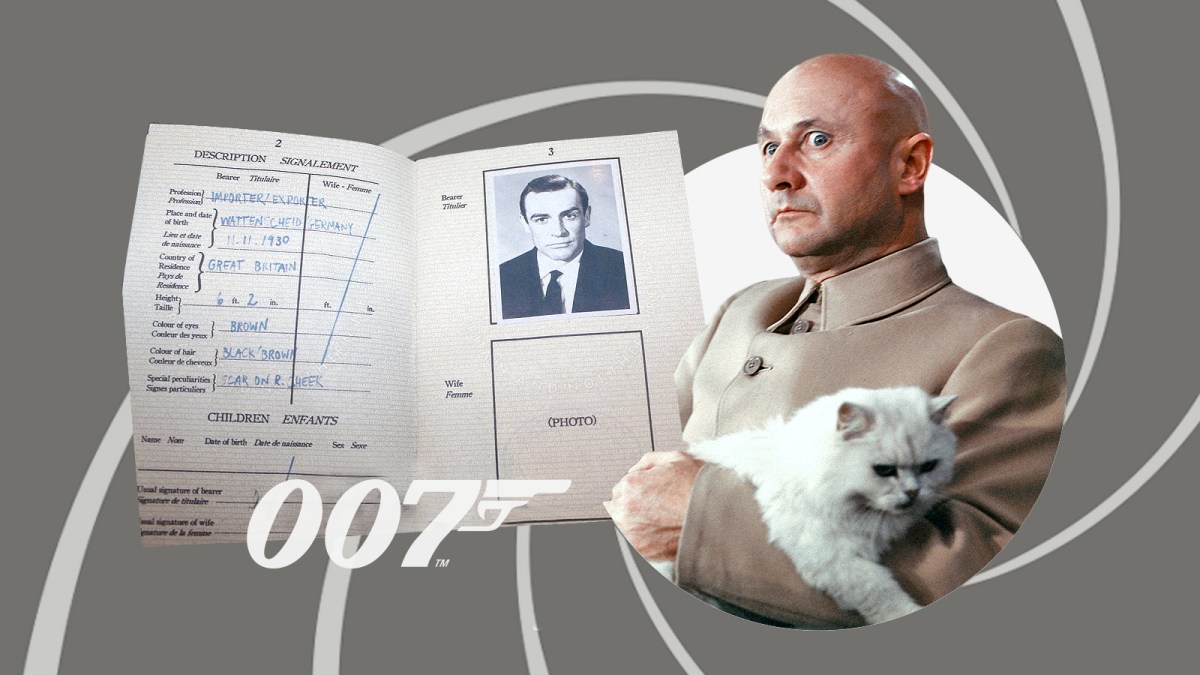

Michael Lonsdale as Hugo Drax

20TH CENTURY FOX

“We believe Fleming saw files seized directly from German weapons companies such as Krupp, Rheinmetall and others,” Tobias Schwesig, the Bond Club chairman, said. “Fleming didn’t have to imagine these dark industrial conspiracies — we believe he saw them directly.”

There is nothing new about the notion that Fleming drew heavily on the Third Reich in his books for a postwar British readership that had fresh and indelible memories of the existential struggle against Nazi dictatorship. The novel claim from the Wattenscheid Bond enthusiasts is that Fleming was quite specifically thinking of intelligence he had picked up on the inner workings of German arms companies.

The Ruhr valley around Bochum was the heartland of Nazi Germany’s defence industry. Thyssen, a steelmaker in Duisburg, provided the backbone of the Wehrmacht’s tanks and warships. Rheinmetall-Borsig, headquartered in Düsseldorf, turned out much of its artillery and ammunition. Mannesmann, also operating from Düsseldorf, furnished it with tubes and steel for military vehicles and oil pipelines.

By the end of the Second World War, these firms had left a long paper trail of illegal rearmament in the Weimar Republic era, and war profiteering and the exploitation of forced labour under the Nazis. In early 1945, as the Allies fought their way through Germany, a group of British commandos known as 30 Assault Unit (30AU), which had been founded by Fleming, were tasked with mopping up enemy documents or other sources of information that might come in handy after the war.

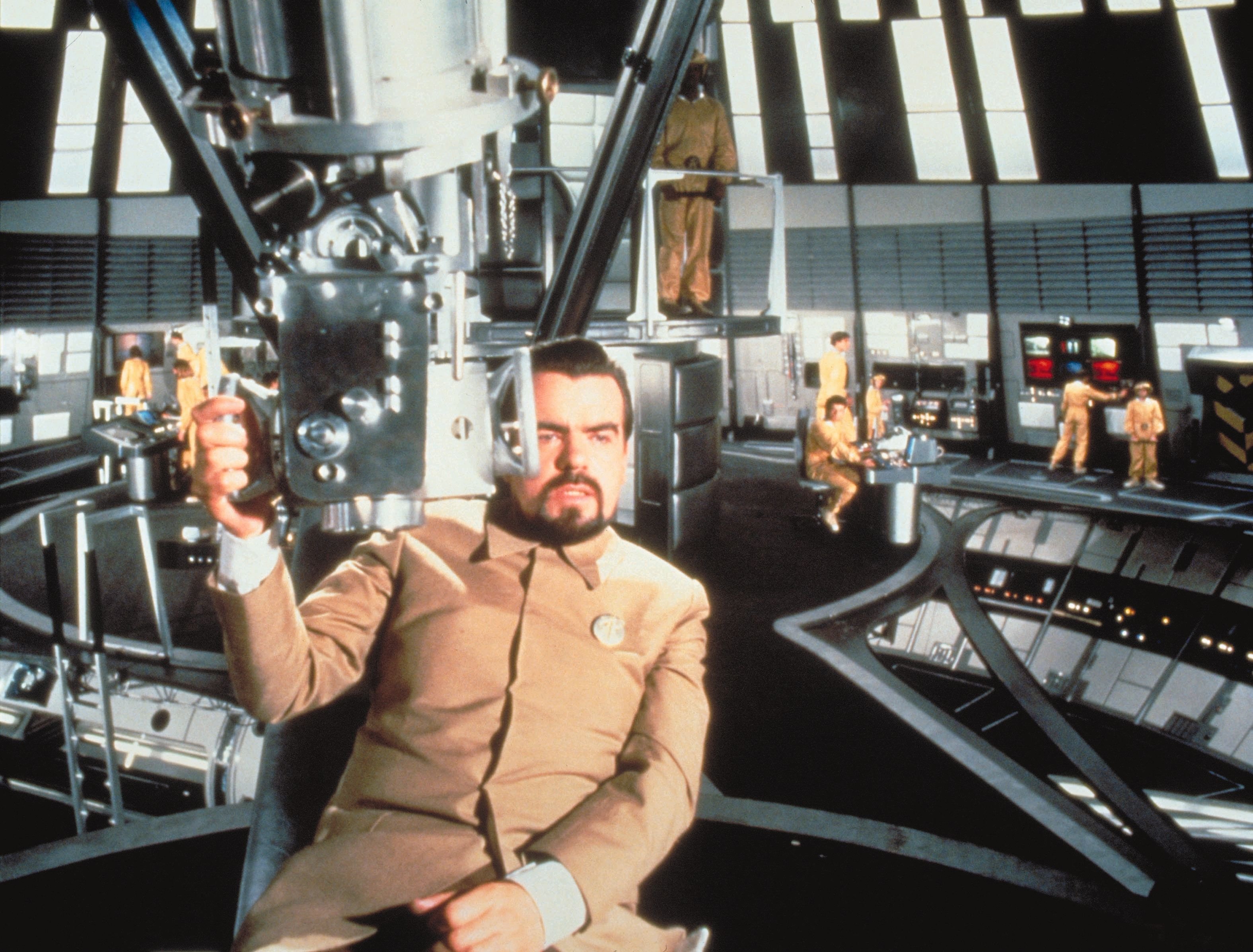

Charles Gray as Ernst Blofeld in Diamonds Are Forever

UNITED ARTISTS

The full extent of the unit’s activities on German soil remains obscure but one of its most important targets was the naval archive at Schloss Tambach, a sprawling baroque country house in the far north of Bavaria.

T-Force, a joint British-American army mission that was significantly larger but performed a similar function to 30AUs, is also known to have raided several German defence-industrial facilities such as the Walter KG complex in Kiel, which worked on propulsion systems for V1 rockets and Messerschmitt and Heinkel fighter aircraft.

• Ian Fleming was as much a womaniser as James Bond. This is his story

Schwesig argues that as a result Fleming, who was heavily involved in both operations, was not only party to the intelligence but used it copiously in his novels. “The villains in Bond feel so real because Fleming knew exactly how Nazi companies operated. This is particularly clear in the character of Hugo Drax in Moonraker,” he said.

The Hungarian-born architect Erno Goldfinger in London in 1968

DAILY EXPRESS/GETTY IMAGES

“In the novel Moonraker Fleming even names the company directly, saying Drax Metals works for Rheinmetall-Borsig, but even without this the parallels are clear. Drax develops alloys for missiles, just as Rheinmetall had done for the V2.”

Schwesig makes the case that the same dark industrial shadows can be seen in Goldfinger and that the villain’s gold-smuggling is based on the tricks that post-Nazi manufacturing tycoons used to launder their illicit wealth.

However, there is at least one Bond villain whose identity was not primarily lifted from the Nazis. Ernst Stavro Blofeld, 007’s perennial nemesis who features in three of the books, may have been based on a Greek arms dealer called Basil Zaharoff, but his name was probably a jibe at Fleming’s old schoolmate Thomas Blofeld, the father of the former BBC cricket commentator Henry Blofeld.