In 2016 Britain narrowly voted to leave the European Union, its closest trading partner, in what critics have called its worst self-inflicted blow in at least 70 years.

The independent Office for Budget Responsibility calculates that Brexit will reduce long term productivity — a perennial problem for the UK — by 4%, which translates into roughly £32 billion ($43 billion) a year. Exports and imports will remain around 15% lower than if Britain had stayed in the EU. Some estimates suggest the European divorce is costing Britain more than £100 billion ($134 billion) annually.

Ironically, immigration, whipped up by Brexit campaigners as a reason to leave Europe, has increased substantially since the vote, and hit a record of nearly a million in the year ending June 2023.

Close to 60% of Britons now think Brexit was a mistake, according to opinion polls. Many who voted to leave, enticed by nationalistic promises of increased sovereignty, say they were lied to and betrayed. Even some previously avid intellectual supporters of leaving the EU believe the deal was a disaster because European bureaucrats have merely been replaced by British ones.

But Brexit’s impact did not end there, far from it. It caused deep cultural and political divisions and redrew the electoral map, fuelling working class support for populist right-wing politicians, despite the fact that they were a leading force behind the now unpopular rupture with Europe.

Political instability

Brexit also ushered in a period of extraordinary political volatility, in stark contrast to Britain’s historic reputation as a solidly stable country.

This volatility can easily be demonstrated by looking at the two general elections since the Brexit vote in 2016.

In 2019, the Conservative Party achieved its greatest victory in 30 years. Boris Johnson, a dishevelled product of Britain’s upper classes with a tenuous relationship with the truth but keen political instincts, became the party’s hero. The Brexit campaign was the primary vehicle by which he won the party leadership.

Five years later, the party was totally crushed, suffering its worst ever electoral defeat. Johnson, overthrown the previous year by his own party after an extraordinary series of outrageous scandals, was one of the leading architects of this debacle.

He has remained in the political wilderness ever since, despite harbouring ambitions to return as a saviour of his party, which even senior figures believe could now become extinct after a 200-year history.

Conservative chaos

Johnson was followed as prime minister by continued chaos. His successor, Liz Truss, tanked the economy and was the shortest serving prime minister in British history. Her successor, Rishi Sunak, suffered a series of political disasters and ran a lacklustre election campaign.

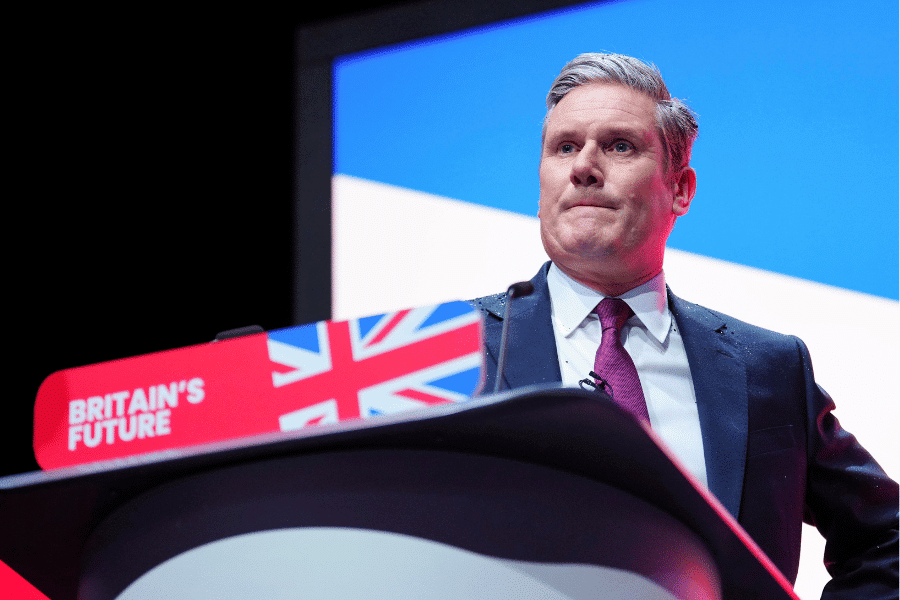

The left-leaning Labour Party, itself crushed in 2019, won power in a landslide in 2024, taking 412 seats in parliament to the Conservatives’ 121. It appeared to have an unassailable majority.

But less than a year after taking power, it looks a lot less secure. In elections in May it lost badly, shedding 187 members of councils that run local government around the country and losing a previously safe seat in the law-making national parliament in London, that went to the insurgent right-wing Reform party of Nigel Farage.

Reform won 677 local seats and control of 10 councils as well as two mayoralties, taking them mostly from the Conservatives.

Although an election is not due until 2029, recent opinion polls suggest Farage’s Reform could win the next vote, despite holding only five parliamentary seats at present. Labour has around 24% of public support compared to 30% for Reform. The Conservatives, under their fourth leader in three years, Kemi Badenoch, are in third place with around 17%.

First past the post

How did all this happen so quickly? There are several answers. One is rooted in Britain’s first-past-the-post electoral system, sometimes called winner-takes-all, where whoever gets the most votes wins, even it it isn’t a majority.

In this kind of election, the number of seats won in parliament does not necessarily reflect the proportion of the vote won; Labour won only 34% of the vote and still ended up with a parliamentary landslide.

In addition, Starmer’s government has made several major blunders, stoking charges that the former barrister is an uncharismatic bureaucrat with questionable political skills, despite his ruthless campaign before the election to move Labour to the centre and counter voters’ fears that it was too left wing.

His government has had some undoubted successes, particularly in foreign policy where Starmer is considered a respected diplomatic operator who has skilfully won the trust of U.S. President Donald Trump, unlike some other European leaders. The two men signed a trade deal this week to lower Trump tariffs on British cars, aluminium, steel and aerospace. Starmer is also a steadfast supporter of Ukraine against Russia together with other European powers.

But in its determination to balance the books after inheriting what it said was a $30 billion hole in the economy, the government has made deeply unpopular and politically inept decisions.

By far the most damaging of these was its decision to remove winter fuel subsidies for pensioners, provoking accusations that older, less wealthy people had to choose between heating and food.

Embarrassing U-turns

Starmer has recently reversed that decision for all except wealthier pensioners, in one of several embarrassing U-turns.

Many Labour party members fear it may be too late to reverse the government’s loss of support, especially since it has signalled it will not go back on another deeply unpopular policy, reducing benefits for disabled people.

Rachel Reeves, the Chancellor of the Exchequer otherwise known as finance minister, has recently announced what the government hopes will be more popular measures, including a massive injection of money into the once respected, now creaking, National Health Service, and into defence.

The latter, mirrored by moves in other European countries, is seen as a necessity in the light of Trump’s uncertain support for Ukraine against Russia and his apparent desire to withdraw from military commitments to the NATO mutual defence alliance.

However, economists warn that Reeves’s room for manoeuvre in funding these policies is fragile, given the weak economy. Her so-called fiscal headroom would disappear if the economy does not revive, especially given possible shocks from the Israel-Iran conflict and the war in Ukraine. If so, she would be forced to either raise taxes or reduce other public services.

The flamboyant Farage

Standing on the sidelines watching these difficulties with glee is Farage, a privately educated, wealthy former commodities trader and life-long Eurosceptic. He somehow manages to appeal to the working classes despite having nothing in common with them, chiefly by fanning the flames of xenophobia.

The flamboyant Farage is a gifted orator and political operator despite having unsuccessfully stood for parliament seven times before being elected in 2024. Some analysts believe that he could become the next prime minister despite the tiny base he currently holds in parliament.

If any individual is responsible for the chaotic events of the last decade it is Farage. The Conservative Party’s fear of losing voters to Farage on the right was behind former Prime Minister David Cameron’s decision to call the Brexit referendum. It was erroneously seen as a way to quell internal party rebellion — until his own party forced him to resign.

The party’s reaction to Farage has been to move further to the right, despite the advice of traditional Conservative grandees who believe this just loses votes in the crucial centre. Conservative supporters, including elected members, are defecting to Farage’s Reform party.

At the same time, Farage is winning support from traditional Labour voters in the so-called Red Wall in the Midlands and north of England, who are worried about immigration and the rising cost of living.

This is at least partly explains why Prime Minister Starmer recently made an aggressive speech about the damage from excessive immigration that seemed to steal rhetoric from the right, dismaying many Labour supporters.

The key to defeating Farage — who may well soon be the official opposition instead of the Conservatives — is improving the economy and controlling immigration. But neither can be considered a given for the beleaguered Labour government.

Still, an election isn’t expected until 2029 and as recent history suggests, a lot can happen in the meantime.

Questions to consider:

1. What was the impact of Brexit on the British economy?

2. Why does the Conservative Party keep moving to the right?

3. If you were Prime Minister of Great Britain, what would be your first priority?