No Welsh Art is a somewhat dizzying exhibition featuring 150 pieces owned by art historian Peter Lord and a further 100 by the Llyfrgell Genedlaethol Cymru – National Library of Wales.

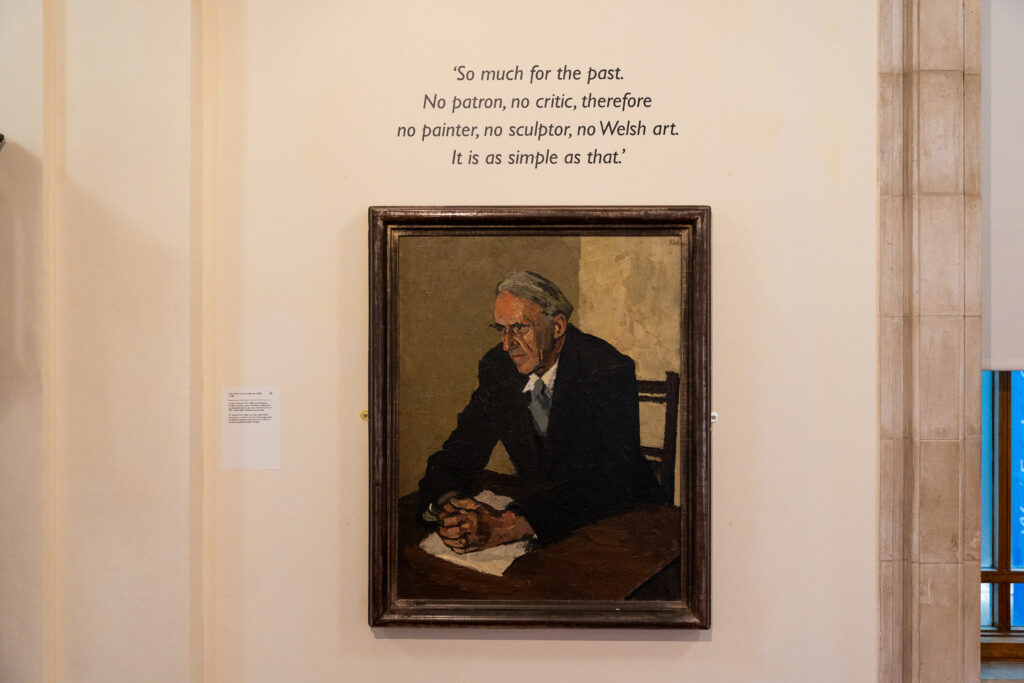

At its heart is a statement made in 1950 by Llewelyn Wyn Griffith, then chair of the Arts Council of Great Britain: “So much for the past. No patron, no critic, therefore no painter, no sculptor, no Welsh art. It’s as simple as that.”

Exasperated by such institutionalised prejudice, Lord has made it his mission to demythologise the prevailing attitudes of Griffith (who was Welsh) and his Anglo-centric peers of the British art establishment.

Chair of the Welsh Committee of the Arts Council of Great Britain, Llewelyn Wyn Griffith – here painted by Welsh artist Kyffin Williams in c.1960 – stated there was “no Welsh art” in 1951, the quote that sparked this exhibition Courtesy of The National Library of Wales

Chair of the Welsh Committee of the Arts Council of Great Britain, Llewelyn Wyn Griffith – here painted by Welsh artist Kyffin Williams in c.1960 – stated there was “no Welsh art” in 1951, the quote that sparked this exhibition Courtesy of The National Library of Wales

This exhibition succeeds in challenging that myth. Viewers are taken on a journey from 17th-century gentry-patronised portraits through artisan painters working for the new middle class, to a wide-ranging taster menu of art depicting Welsh landscape and society, and finally 20th century and contemporary art.

Griffith was wrong. There were patrons and critics. And there was, and is, Welsh art.

The Finding of Taliesin, 1878, by Henry Clarence Whaite Courtesy of The National Library of Wales

The Finding of Taliesin, 1878, by Henry Clarence Whaite Courtesy of The National Library of Wales

That is not to say that all the art on show is of high quality, although much of it is. So, for instance, works that my museum curator friend enjoyed for the humanity they reveal were found “ghastly” by my artist-art-historian friend in respect to their execution.

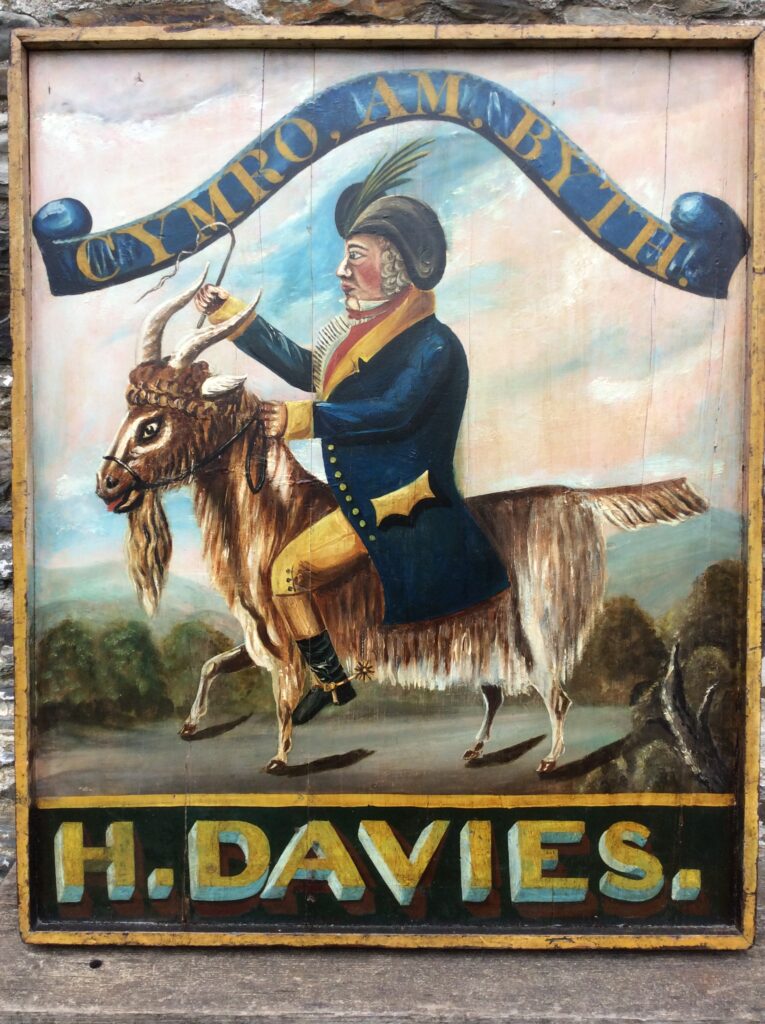

Lord’s aim was to showcase the visual environment in which art in Wales evolved. One striking example of influence is the pub sign displayed next to a quote from sculptor John Gibson (1790-1886) who, as a child, admired the signs that swung above taverns.

Lord’s collection includes the rare Hanner-y-Ffordd inn sign, Conwy Valley, 1835 Peter Lord Collection

Lord’s collection includes the rare Hanner-y-Ffordd inn sign, Conwy Valley, 1835 Peter Lord Collection

“This is the piece I’d save from the flames. It was black when I got it. Rare as hen’s teeth,” says Lord, who is as keen to challenge the snobbery of Griffith’s statement as he is the bigotry.

Why did Griffith say what he did? Why did it matter, and, 75 years later, does it still? I doubt many Welsh artists cared about the snub. A radical modern tradition was evolving then and continues to flourish. To many Welsh artists, art is by nature international and cross-cultural.

In the words of my artist friend: “To make art a servant of nationalism is to shrink it.” To him, Griffith’s claim is not worth being bothered by, especially today. Many contemporary regional galleries and national eisteddfodau (Welsh cultural festivals) reveal Welsh visual art is in rude health.

Focus on | Concept and curation

The exhibition is unusual both for its sociological approach to interpreting the history of Welsh visual culture, and because 150 of the 250 artefacts on display come from my own collection.

As I have lived with some of them for 40 years, they are deeply familiar to me. Most of the works from the National Library collection were also known to me, but in a less intimate way.

The task was to integrate the two collections to create a balanced narrative. The relative proportion of works from the collections varies from section to section.

For instance, the interpretation of 19th-century itinerant portrait painting is achieved largely by works from my own collection. The library’s holdings are dominated by the interpretation of high-art gentry patronage.

The exhibition narrative expresses the evolution of my ideas over four decades. My 2016 volume, The Tradition: A New History of Welsh Art, republished by Parthian for the exhibition, is effectively the catalogue. However, the opportunity to express that narrative in physical form presented both an opportunity and a particular problem.

The opportunity was to create a model for the national gallery of Welsh visual culture that the nation does not, at present, possess. The problem was to do so with works from just two collections and in a space that was not designed for that purpose.

The Gregynog Gallery at the National Library is huge, and beautiful as an empty space, but difficult for narrative exhibitions. The answer was to divide it to suggest themed rooms, colour-coded with the interpretation. The aim was not to lose the visitor through manifestations of Welsh patronage, the history of our art history, and expressions by artists of the nation’s complex sense of self.

Peter Lord is an art historian and collector and curated the No Welsh Art exhibition

Yet to others the criticism still stings. Griffith’s observation isn’t surprising to anyone immersed in issues pertaining to Cymru, Cymraeg and Cymreictod (Wales, Welsh language and Welshness). Since Edward I’s colonisation (1277-83), Welsh sport, music, art, literature, film, education, energy projects, politics and language have all been subjected to either ignorant or patronising attitudes by the noisy neighbour across Offa’s Dyke.

The exhibition is divided into 14 sections. In the Welsh Identities: How They Saw Us section is a sequence of 19th-century London-made prints depicting Welsh people as stupid (on account of not being able to speak English) and poor, wearing leeks in their hats and riding goats. To me, these images provide context for Griffith’s remark. Such images are relevant to contemporary conversations about racism and colonialism.

Curator Peter Lord giving a tour of the exhibition Courtesy of The National Library of Wales

Curator Peter Lord giving a tour of the exhibition Courtesy of The National Library of Wales

To Lord, Griffith’s statement contributed to a national lack of confidence that left Wales – in contrast to other small nations – without its own national gallery.

National pride

Thank goodness then, for the National Library. This is a fully accessible venue on Penglais Hill with grand views of Aberystwyth and the sea, good public transport and a car park.

Other exhibitions include the permanent On Air: A Century of Broadcasting in Wales, and Treasures. They provide excellent context to No Welsh Art, while also helping to unpack the myth.

Importantly, because you need a good deal of time to appreciate No Welsh Art, there is also a cafe, shop and sofas galore.

Navigation of No Welsh Art is aided by colour-coding. A downloadable audio tour examines 11 pieces in more depth. Booklets in English and Welsh include the introductory texts of each section. The activity guide for children is particularly good, given that, without it, the exhibition is aimed at adults. Furthermore, there is a monthly guided tour and several planned events.

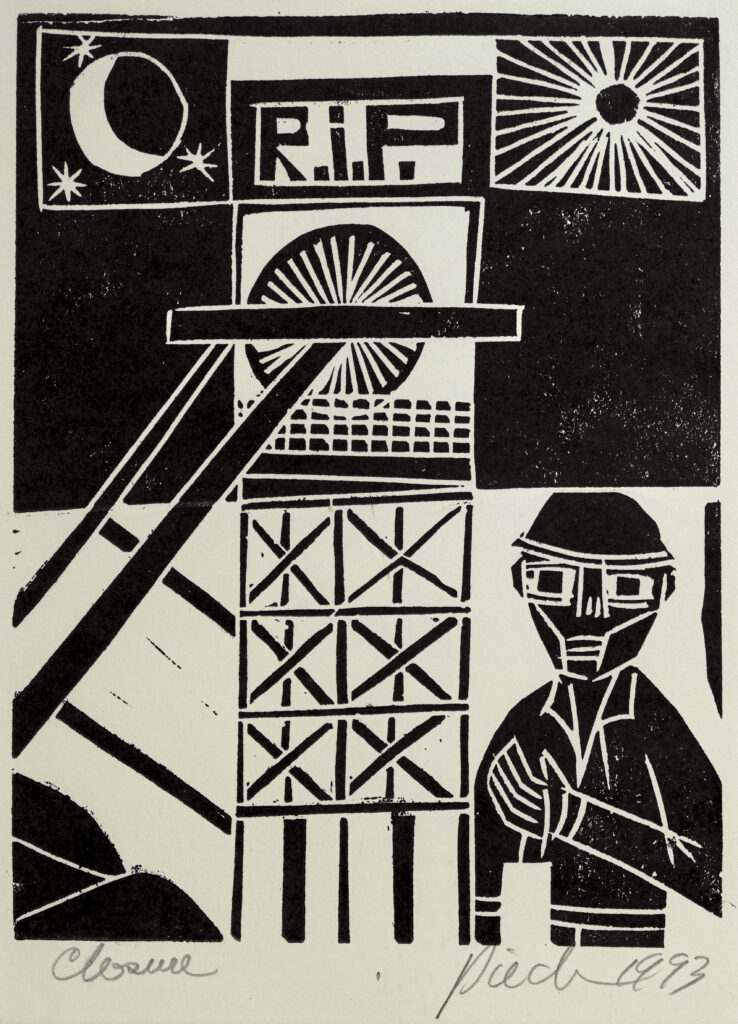

Closure, 1993, by Paul Peter Piech, depicts the plight of minersPeter Lord Collection

Closure, 1993, by Paul Peter Piech, depicts the plight of minersPeter Lord Collection

Word to the wise

An appreciation of the exhibits is made richer by the wordy labels. The print is small and not easily read, and while many are visible to wheelchair-users, some are so low you have to stoop. But ignore the interpretation text at your peril. I have overheard visitors who didn’t read the labels mutter disconsolately about the number of portraits, while those who did were engaged.

There’s a lot to digest. Lord’s passion is evident, particularly for the 19th-century artisanal art. A wealth of intrigue and detail is revealed in the text and the subtle ways in which the pieces interrelate is satisfying. I found the notion of transient artists hobnobbing with fellow itinerant poets particularly illuminating. The curator’s delight in this 19th-century artisan period is so evident the exhibition feels a little weighted in its favour.

An aerial view of the National Library of Wales in AberystwythCourtesy of the National Library of Wales

An aerial view of the National Library of Wales in AberystwythCourtesy of the National Library of Wales

By comparison, the 20th- and 21st-century representation seems more piecemeal, and the accompanying text less vivid. Nevertheless, it emphatically demonstrates that great Welsh art existed even while Griffith uttered his complaint. And it contains real treasures, such as several 20th-century paintings of miners by miner-artists such as Archie Rhys Griffiths (1902-1971), Vincent Evans (1896-1976) and Nicholas Evans (1907-2004).

Look at these paintings. They summon feelings of empathy, struggle, dignity, wonder and want, grief and injustice, and are atmosphere rich, even though this lofty light-filled gallery couldn’t differ more from the south Wales coal mines they depict.

Valiant Heritage – Harlech Castle at Dusk, 1927, by Clara Knight

Valiant Heritage – Harlech Castle at Dusk, 1927, by Clara Knight

This might feel like several exhibitions amalgamated into one. But abundance is not necessarily a bad thing and in this case serves as evidential proof. If you are willing and able to devote time (and don’t forget your glasses) to No Welsh Art, there is much here to learn and enjoy.

Julie Brominicks studied fine art and art history at Aberystwyth University. She is the author of The Edge of Cymru

Project data

Howard Macro Conservation

Art Works Exhibition Services

ACT Reprographics; Rebus Cymru

Enjoy this article?

Most Museums Journal content is only available to members. Join the MA to get full access to the latest thinking and trends from across the sector, case studies and best practice advice.