Since the 2016 Brexit referendum and the final Brexit vote in 2020, the United Kingdom (UK) and the European Union (EU) have had a fluctuating relationship on security aspects, particularly in light of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. Therefore, discourses surrounding the possibility of re-accession and reintegration of the UK back into the EU have started to emerge (Walker, 2025). The fragile security within the region pushes the UK to reconsider its perception and cooperation with the EU. The danger of the post-Soviet “Thucydides Trap” between Russia and the EU post-Soviet adds to the complexity of the security struggle, as Russia’s invasion of Ukraine demonstrates the decrease of Russia’s influence in its former ascendancy (Gleichgewicht, 2022).

The Western values, influence, and power within their institutions are perceived as threats to Russia, causing Russia to be trapped in a zero-sum game (Hrabina, 2023). The anxieties of losing legitimacy, power, and sovereignty of Russia over the region are a reflection of the “Thucydides Trap.” Russia’s failure in establishing policies that are powerful enough to influence post-Soviet countries is reflected in the shift of post-Soviet countries from Soviet satellites into pro-Western countries (Hrabina, 2023). From the Russo-Georgian War up until the annexation of Crimea, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine can be seen as a pattern—making it expected to happen (Hrabina, 2023).

Following the Brexit phenomenon, the UK has been facing a security dilemma—specifically, it is trapped in the post-Soviet “Thucydides Trap” as it is a part of the Western power but is separated from the more “centralized” EU. The emergence of gaining more influence and power inside the potential trap affects its decision-making process in practicing its foreign policies; one of them is reintegrating back to the EU.

The “Thucydides Trap” in Post-Soviet Context

The term “Thucydides Trap” originates from the Greek historian, Thucydides, who observed and argued that the fast revolt of Athens against Sparta created a chain of fear for Sparta, making both of them meet the inevitability of war—therefore, the Peloponnesian War broke out (Hrabina, 2023). The concept of the “Thucydides Trap” tries to explain that the proneness to war could appear in a condition where an emerging power threatens a dominant power—which also emphasizes the importance of a cooperation framework to escape from the trap or to prevent the trap from creating a fatal escalation of the conflict (Gleichgewicht, 2022). Therefore, in the post-Soviet context, the decline of Russia’s power in its former ascendancy and the aggression that goes along with it made it possible for the West’s economic and democratic power to end up competing with Russian capitalism naturally—subsequently making the region prone to war (Gleichgewicht, 2022).

To understand the “Thucydides Trap” in the contemporary context, Russia can be seen as the equivalent of “Sparta,” referring to its dominance in the post-Soviet region—whereas the EU and NATO are the equivalent of “Athena,” referring to the power and influence takeover in the region. If countries such as Ukraine, Georgia, and Moldova began showing their pro-Western side, Russia would see this as a threat to its power dominance in its ascendancy (Hrabina, 2023). Russia’s aggression creates a disturbance in the European region, including the UK as a former EU member state. In response to this threat, the UK’s discourse of reintegration can be seen as classical power-balancing (Morgenthau, 1948, p. 13). The discourse on reintegration continued until the British Parliament held a debate on the issue, as evidenced by the 132,500+ signatures of the petition calling for the UK to rejoin the EU as a full member on March 18, 2025 (Fella, 2025). The topic of re-accession was brought up in the parliamentary debate on March 24, 2025 (Fella, 2025).

The EU’s Expectation and Capability Gap

In adherence to its strategic autonomy, the EU believes that a cooperation framework with the UK makes sense, as the EU has also been exerting efforts to deter Russia’s attacks, and it is in line with the UK’s goals. From this angle, both the EU and the UK can be seen as international actors that seek each other’s support to establish a balanced power—subsequently, escaping the post-Soviet “Thucydides Trap.” As a normative power, the EU is also expected to have the central role in security and global development. However, for the UK to reintegrate back into the EU, both the UK and the EU have to go through a complex process—making it less likely to happen—such as the absence of specific requests from political parties in the UK for re-accession, the complexity of treaty reformation, and the refusal from the EU to repeat Brexit’s instability. Since Brexit happened after various crises such as the financial crisis in 2009, the Eurozone crisis in 2013, and the migration crisis in 2015, the EU’s role as a global actor became unsteady and subsequently affected some member states—especially prior electoral seasons in France and Germany (Apetroe, 2018). Furthermore, the EU’s security instability is reflected in the weakened cooperation in responding to emerging challenges and geopolitical tensions.

The EU’s financial shortfall post-Brexit was estimated to be more than €10 billion per year. As the most significant contributors to the EU budget, its departure from the EU created a larger gap in the funding area. For instance, under the UK’s replacement funding program, Scotland has lost more than £300 million of European support in 2022 (Scottish Government, 2022). Moreover, Scotland is suffering from 60% of financial support compared to the first payment by the UK government (Scottish Government, 2022). The promise made by the UK government to continue the payment post-Brexit only resulted in less than half of what it ought to have been—precisely £212 from £549 in a three-year ‘period (Scottish Government, 2022). The EU’s budget for programs pursuing “smart, sustainable, and inclusive growth” could also potentially be reduced from 35% to 30% of the budget in response to the funding shortage (Haas & Rubio, 2017).

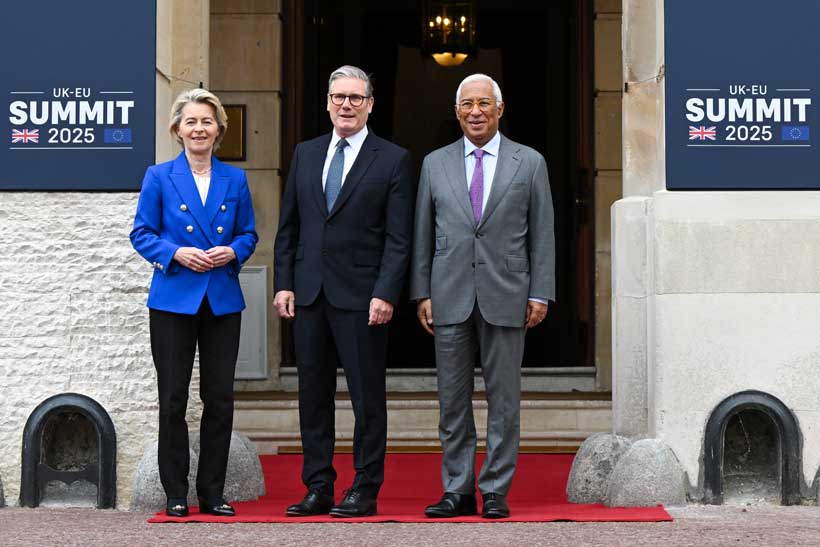

The weight of risks in the potential re-accession became the capability gap that the EU possessed to not be able to give the full membership back to the UK. The EU is not the most capable power to easily regain stability—both in response to the members’ departure or re-accession and the risk of potential tension in between. In spite of the EU’s expectation-capability gap, the EU and the UK seek another way to reset the relationship and to create a cooperation framework with the same goal—precisely, to escape from the post-Soviet “Thucydides Trap.” The overlapping view of Russia by the EU and the UK is reflected in its sanctions mechanism towards Russia’s aggression. In 2024, the EU conducted sanctions on Russia on behalf of the death of Alexei Navalny—a Russian opposition leader—that consisted of asset freezes, travel bans, and a prohibition on providing economic resources to Russia (European Council, 2024). Subsequently, in 2025, the UK declared 100 sanctions on Russia’s energy, financial, and military sectors—moreover, restricting oil trade as the primary resource for Russia’s war machine (UK Government, 2025). Following this, the EU–UK Summit on May 19, 2025, shows the commitment between the EU and the UK to strengthen cooperation in response to the threatening geopolitical situation. At the summit, it was also declared that the EU and the UK are “like-minded” partners that share common interests (European Union, 2025).

In conclusion, the EU and its expectation-capability gap contribute to the impracticality of the UK’s re-accession to escape the post-Soviet “Thucydides Trap” by creating a security alliance in response to Russia’s aggression towards Ukraine. The expectation of being the central power for security and global development is not comparable to the weight of risk the EU might face—specifically regarding its refusal to repeat the Brexit and post-Brexit instability. Even though the EU isn’t fully capable of fulfilling the expectations of granting full membership to the UK, some other cooperation frameworks have been made in the effort to reset and reharmonize the relationship between the EU and the UK—especially in the security and defense area through the EU–UK Summit.