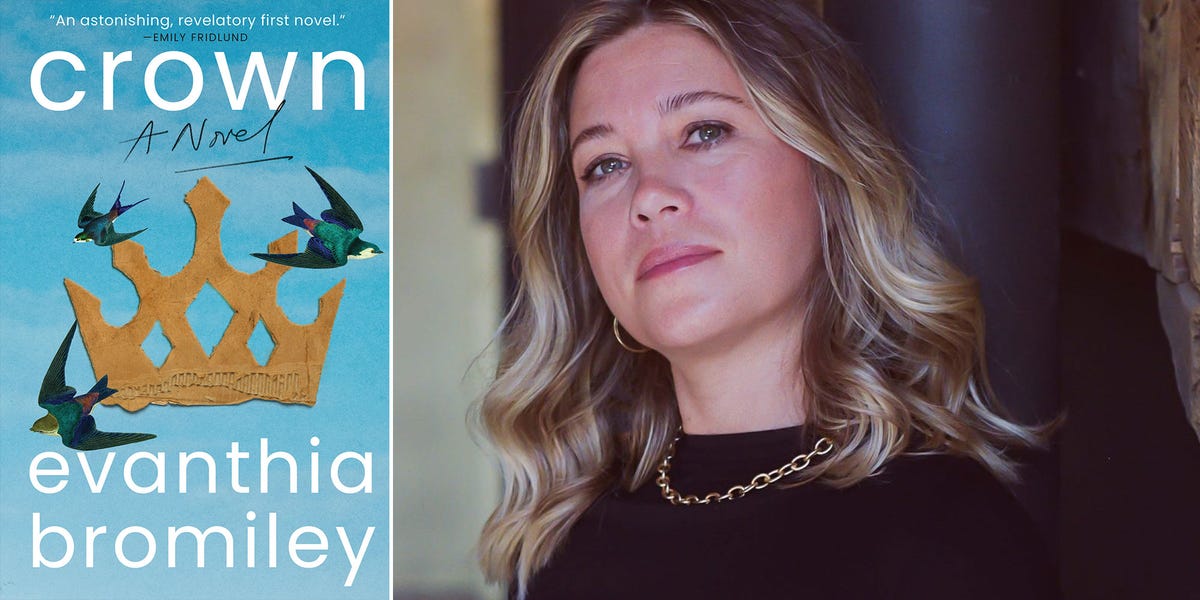

It’s hard to be a human inside the system,” Evanthia Bromiley says from Colorado as we speak over Zoom about her lyrical debut novel, Crown, which tells the story of resourceful nine-year-old twins Virginia and Evan and their pregnant single mother, Jude, who live in a trailer park near a river in the Southwest. The book unfolds over three days during the coronavirus pandemic. On the first day, Jude receives an eviction notice while she’s out of work and on the precipice of going into labor with her third child. She has no health insurance.

Focused on making ends meet, Jude frequently needs to leave her children to their own devices—there are a few harrowing episodes in the novel, especially after Jude goes to the hospital to deliver the baby at night, leaving the twins in a car parked in a field nearby to wait for her. (They don’t.) Much of the novel’s suspense arises from the question of whether these three have a chance at making it.

It’s not only imaginative prowess that shapes the psychological realism and the compassionate vision that lie at the heart of the novel. Bromiley spent the past 20 years of her life teaching in Title I public schools, where a significant percentage of the children live below the poverty line. For a while, she taught a program for kids she identified as creative and talented, working with them from third through fifth grade. “I knew their families intimately, and I knew the kids, and all we did was read great books and write great stories based on the craft, based on the great books.”

Listening to children’s stories was part of how she discovered their resilience, Bromiley tells me. For instance, one of the little boys was unhoused and lived with vouchers in a hotel room with his family but began breeding salamanders and selling them to other children at school for $5 or $10. This kind of teaching experience awakened her to the importance of showing Virginia’s and Evan’s resilience too. “If they’re hungry, they find food,” the author says. “If they need some information in their life, they make it up. Their intimacy with each other is how they not only survive but find a lot of joy.… The life of a child is resilient and full of joy, regardless of the structures around them crumbling or creating the ceiling that they’re banging against.”

Crown stands out not only for the sincerity with which it approaches its characters’ struggles with housing, food, and medical care—the way in which people are both individuals and parts of families—but also in its stunning formal choices. First, the structure. The story originated with Virginia and her voice, but initially, Bromiley wrote the book with an omniscient narrator, only to realize later that the story was intimate and “very rooted in the body” and should therefore be in the alternating first-person voices of Virginia, Evan, and Jude. The author also wrote a great deal of backstory, much of which she carved away from the novel, including Jude’s personal history—we receive a snippet about the twins’ father, but Jude is in survival mode, where she doesn’t often have time to reminisce about her past romantic life, Bromiley says; the kids are living more in the moment. “It was a prismatic account,” Bromiley explains. “It felt like a triptych, where they were bouncing off each other in this particular time period.”

Bromiley is not a twin, but growing up, she and her brother had a childhood that was “pretty free and unlimited” and influenced by landscape. The setting of the novel is the blue-collar Southwest or more specifically, a sagebrush-heavy corner of Colorado—full of cottonwoods and touching Utah and New Mexico and Arizona—that Bromiley, who lives in that corner, says has diverse landscapes: “You can be in the desert in half an hour here on the Colorado Plateau, or you can be up in the San Juan Mountains, or right outside my door is the river that runs through the novel, which is really important to the characters, especially the children, as they kind of undergo this nightlong journey.” Bromiley sees Crown as a novel of the West. “While writing it,” she says, “I hesitated to name the specific town and landmarks. I think that’s because I felt like the systems that the characters were encountering are American systems that they could have encountered in any town in the West.”

An inventive technique she uses is to intersperse the unattributed dialogue of people around the principal characters as a way of creating an unusual aspect of setting: the sounds of what it’s like to be alive in that place. Bromiley remarks that she loves “the terroir, the language around here, the dialogue of the people who live around where I live, and so I wanted to capture that energy on the page.” Sometimes that dialogue is “aligned right on the page to show texture and energy.” This unusual formatting can also convey on a more visceral level the dark severity of what’s happening in the book, as in this oblique passage, which comes after we learn glancingly that social workers once took Virginia and Evan:

We’re hungry. We’re hungry, and it is your job to feed us!

Make something, says the door.

There’s nothing to even make.

There’s a ten and a five in my purse.

So what? So what?

Go to the store. Get whatever it is you want.

One has the sense, reading these dialogue snippets, that Bromiley is keenly attentive, as poets are, to how things feel. Her process with the book involved many decisions about what kinds of friction she wanted to create by setting one section against another and “what kind of shock or surprise or what kind of intimacy” would be generated by different placements. Also like a poet, she seems to appreciate white space in which “nobody’s talking and the reader gets to pour herself in there.” Her writing habits reflect a kind of porousness around language and sense impression too: She writes early in the morning, never at night, but also says that she can write anywhere if she shows up and doesn’t talk too much or interact too much with the world ahead of time.

Bromiley’s intent was to depict the “incendiary event of an eviction” that will lead to a family’s becoming unhoused from land that they love. While the situation is painful, in Bromiley’s telling, it’s still suffused with beauty. Here is how Jude sees the trailer park, even after the sheriff adheres the eviction notice to the door: “I like at night how the naked windows show each trailer’s bright heart, lit up from the inside and how all the human ordinariness is exposed.” There is darkness in the looming threat of the state coming to take the kids, the mysterious absence of the twins’ father, and whether the family can survive within a system we see is harsh. But throughout threads a raucous joy that the twins find and make for each other.

As Bromiley points out, “there’s a lot of hope at the end of the journey too, because there’s this new baby coming, and that regardless of what kind of world that child’s born into, that child’s going to be loved.”•

CROWN, BY EVANTHIA BROMILEY